.

.

In what ways do great children’s books influence the culture? In the era of Harry Potter the main route is via commodification. In an earlier era, influence might have taken an indirect path, mediated by contemporary literature.

Take the case of Virginia Lee Burton’s “The Little House,” a children’s book published in 1942 that received immediate (and lasting) popular and critical success. Consider the effect its text and illustrations may have had on the imaginations of Anne Tyler and Arthur Miller.

Anne Tyler’s House

I came to read “The Little House” only recently, after learning it is Anne Tyler’s “life long favorite picture book.” Tyler explained her love of the tale in an essay published in The New York Times Book Review in 1986 entitled “Why I Still Treasure ‘The Little House’.” Tyler vividly remembers her mother reading the book to her at age four. When she became a mother herself, Tyler enjoyed reading it to her two daughters. She guesses she’s given away “several dozen copies” of the book as gifts to new babies. In a more recent written interview conducted in 2004, Tyler said she has long been in awe of how Virginia Lee Burton managed to say “everything possible about change and loss and the passage of time.” Plainly this is an example of like attracting like, for in her own 18 novels Tyler has done the same.

In her essay Tyler mentions one thing that’s always eluded her:

I have pondered for years, for decades, over the final picture of the Little House. She’s on a hill again; she’s surrounded by apple trees again–but there is no longer a pond! It’s as if the story ended, “She lived happily ever after–but not quite.” Could it have been just an oversight? A failure on the part of the author-artist to recognize the importance of a pond? Or did she intend to remind us of the grim facts? “You can go back, but never all the way back,” she may have been saying. “What is done can be undone, but never completely.”

.

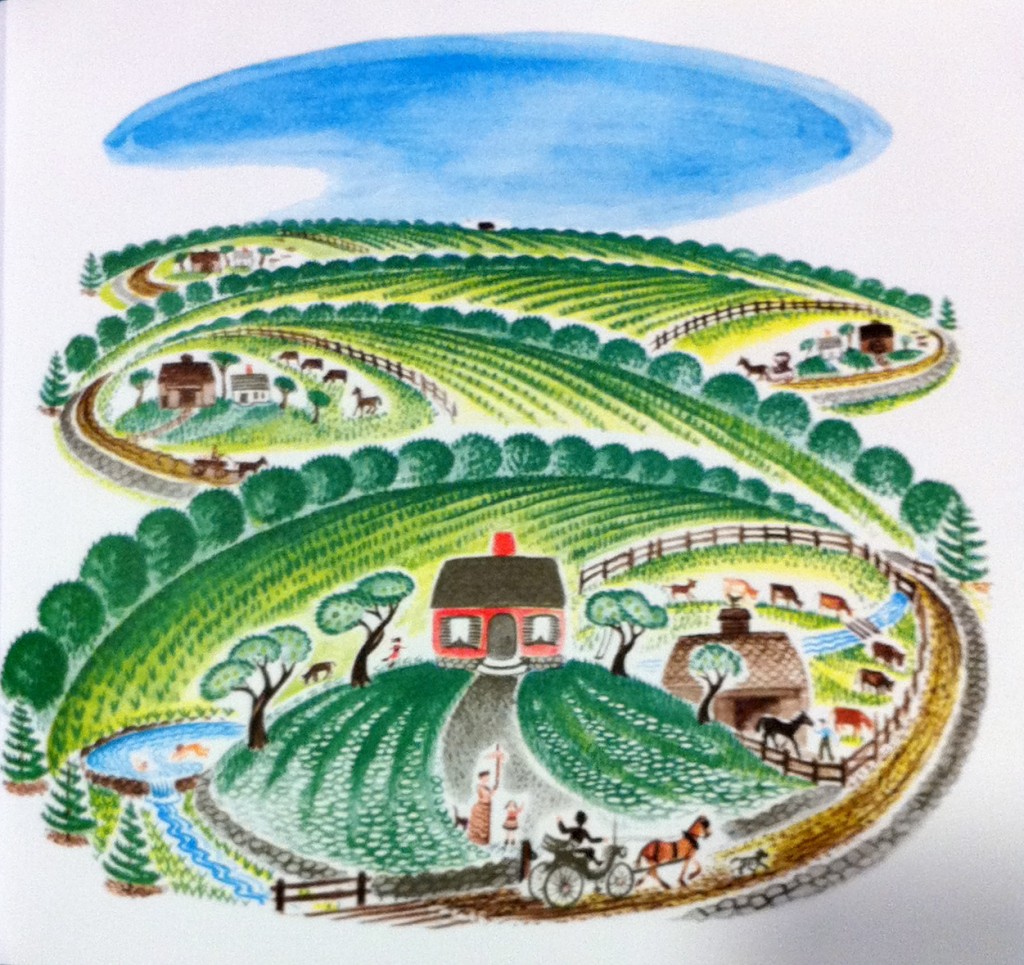

The Little House (note the pond to the left) before an expanding city overruns it (page 9):

.

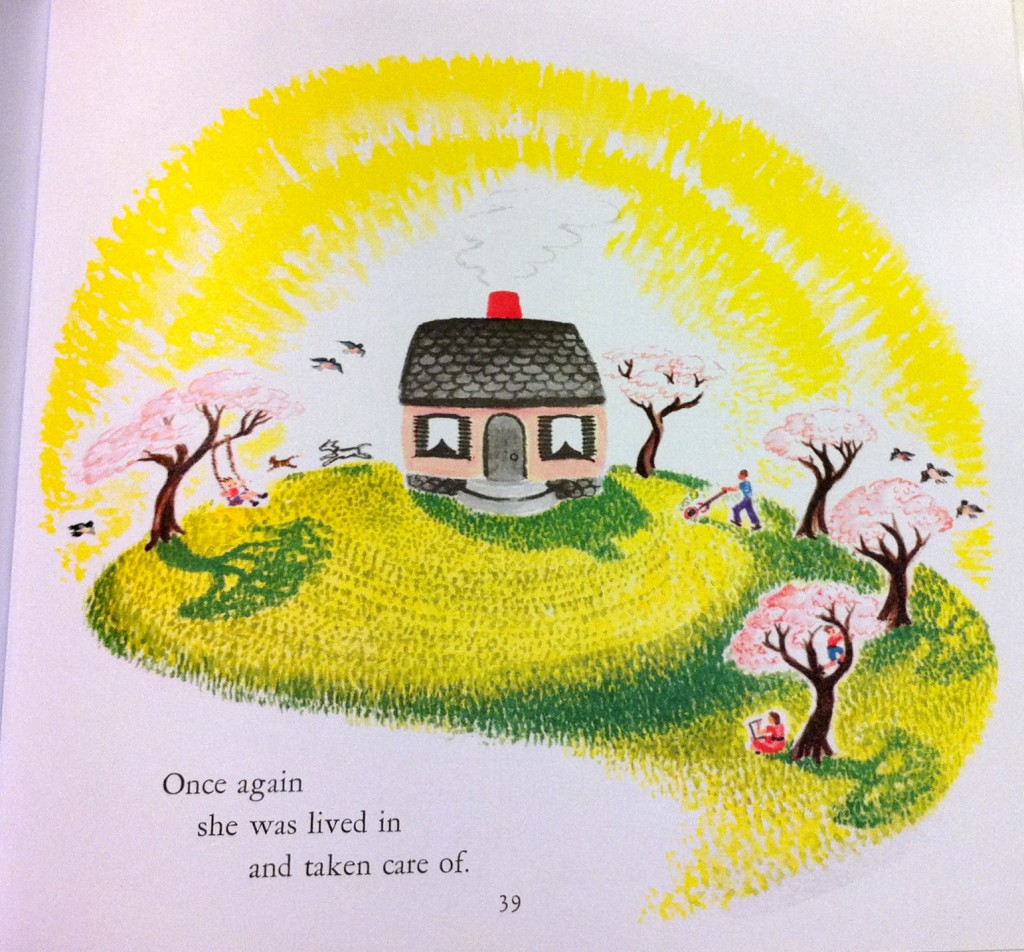

The Little House after it is moved to a new perch in the country (page 39):

.

I see this final picture differently. Only the house and its immediate lawn survive because there is only so much room in God’s heaven. Yes, I interpret the story as a Christian allegory.

On the first page of “The Little House” the reader meets a father who is described as “the man who built her [the house] so well.” With an air of omniscience he predicts the house will live forever. His prophesy includes a stern and very Biblical sounding admonition: the house “shall never be sold for gold or silver.” I think we are meant to understand this as a warning against betrayal.

A second voice appears on page 32. Many years have passed. The house has been swallowed up by the city and is abandoned. We sense we are coming to the fulfillment of the story. Or call it “her-story,” as Burton, who created all the illustrations, wittily indicates below the front door mat on the cover illustration. This new voice belongs to one of the father’s offspring. In a clever bit of misdirection on Burton’s part, it is not the father’s son, but a more distant (female) descendant, “the great-great-granddaughter of the man who built the Little House so well.” She is here to fulfill a destiny, however. She will bring salvation to a soul true and pure (we are told that while the house is “broken … crooked … shabby,” it is “just as good a house as ever underneath.”).

Study the pictures on pages 31 and 33:

.

.

.

Whatever the condition of its soul, surely these are images of death. Executed in tones of gray and black (see how the fading pink of the first picture expires in the final shot), the pictures include a cross made of wood planks marking the door between dead-eyed windows.

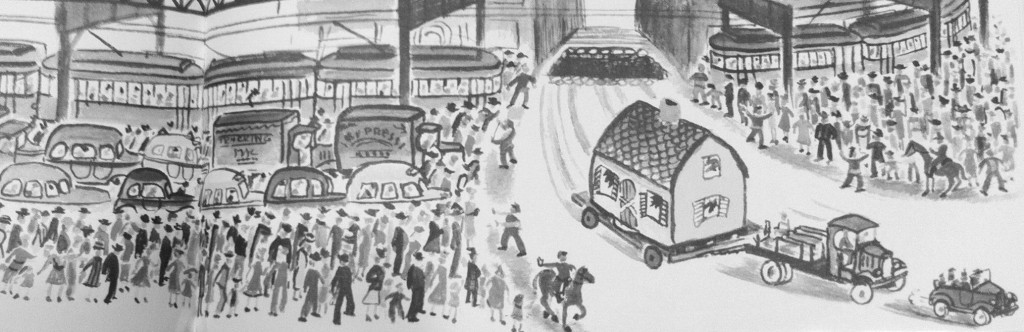

The great-great-granddaughter’s mission is to be the house’s travel guide to what she calls “just the place” — an afterlife in a revived Eden that simulates the house’s original home set in nature. The journey is depicted in a two-page spread on pages 34-35. It is a scene akin to a traffic-stopping funeral procession:

.

.

Look closely again at the after-the-move illustration further above — the “after salvation” picture (my preferred label) that has always given Tyler pause because of the omission of a nearby pond. Notice how Burton re-conceives the house’s surroundings as a protective island of contentment. The image is gently rounded and isolated in white space, appropriate to a vision or dream. There is a free-floating — and, to my eyes, heavenly — aura to the picture. That the house is no longer earth-bound is also suggested by how the image and text are positioned on the page. Of all the illustrations in the book, those found on the final three pages — 38 and 39 (which I view as a connected spread) and 40 — are the only places where the text is allowed to appear beneath the image. The effect is telling. The image is lifted up. It rises above our focus as we read, as if to say the Little House is no longer among the creatures here below.

You may scoff at this interpretation. I suspect Anne Tyler would too. But I think we should leave open the possibility that, within her own masterful explorations of “change and loss and the passage of time,” the caution that Tyler exhibits — a sentimental reticence to stir up all that lies at the dark bottom of the river of time — may be traced back to a comfortable understanding of the world (“rescue is possible; conditions can be reversed”) she constructed when, as a child, she listened to her mother read “The Little House.”

Arthur Miller’s House

Let me turn from armchair psychologizing to pure speculation. Consider next the case of Arthur Miller, on whom the influence of “The Little House” is, as far as I know, undocumented. Will you hear me out?

In the middle section of “The Little House” Virginia Lee Burton describes and provides illustrations of the menacing encroachment of a city, bent on swallowing up a pastoral setting. What I ask is this:

Is it a coincidence that just a few years after the release and popularity of “The Little House” and at a time when Miller and his wife might well have been accumulating children’s books to read to their young daughter, the playwright chose to write stage directions for “Death of a Salesman” that share not only the dread but the specific details of Virginia Lee Burton’s vision of the city?

As a prelude before the curtain rises on “Death of a Salesman,” Miller offers the audience what an evocation in music reminiscent of the bucolic setting in initial pages of “The Little House.” He specifies: “A melody is heard, played upon a flute. It is small and fine, telling of grass and trees and the horizon.”

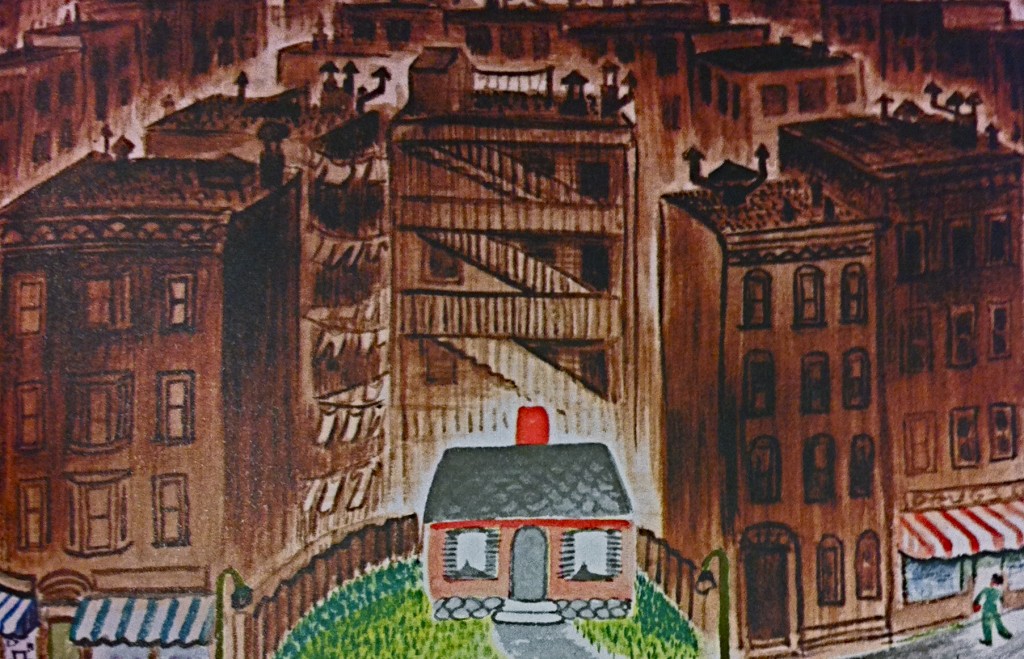

Fast forward: the horizon has disappeared. Here is Burton’s illustration of the urban reality (page 19 of “The Little House”):

.

.

And here is how Miller sets the scene for his tragedy:

“The curtain rises. Before us is the Salesman’s house. We are aware of towering, angular shapes behind it, surrounding it on all sides. … As more light appears we see a solid vault of apartment houses around the small, fragile-seeming home. An air of the dream clings to the place, a dream rising out of reality.”

Burton’s lament (“No one wanted to live in her and take care of her any more”) is echoed by Willy Loman: “Figure it out. Work a lifetime to pay off a house. You finally own it, and there’s nobody to live in it.”

.

[A review of “The Little House” is posted on Amazon, here.]

.

.