Seven times I have tried to get the New Yorker magazine to recognize my cartoon-caption-writing prowess. Seven times I’ve been snubbed. Not one of my seven entries has been crowned with the laurels of finalist (for each contest three finalists are chosen), let alone winner. Each stinging rejection was unfair.

Demonstrably unfair.

Let me demonstrate.

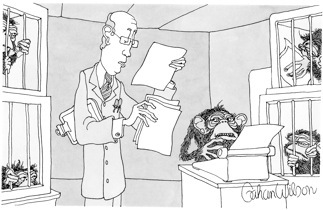

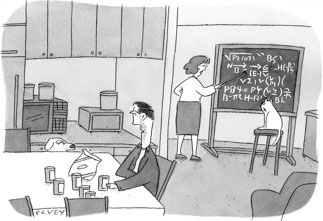

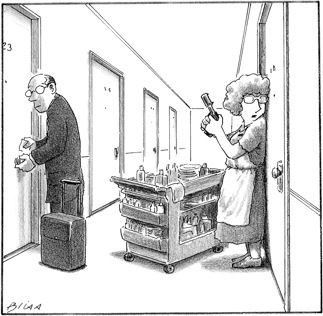

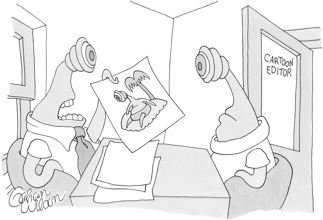

Below are the seven initially silent cartoons, each followed by four captions suggested by contest entrants. Every set of four includes my own submission mixed in with the three finalists. See if you can spot the the one — mine — that somehow just doesn’t belong in the same class.

. . .

“Have you considered writing this story in the third monkey rather than the first monkey?”

“This page — the one that begins, ‘Who’s there?’ — keep working on that.”

“We’ll have to run it by our infinite number of editors.”

“Sorry, guys. It’s another rejection letter. ”

. . .

“You want to impress me? Drive to the store and get me more beer.”

“Lemme tell ya — and this is from personal experience — knowing how to roll over and play dead comes in much more handy. ”

“Don’t worry—they’ll never actually build it.”

“Trust me, my lessons have way more real-world applications.”

. . .

“He’s always thinking outside the rock.”

“His heart is set on finding a vintage woolly Plymouth.”

“He needed a place to park his wheel.”

“Yeah, but the weirdest thing was, once he built it I suddenly felt compelled to give him a list of things to do around it.”

. . .

“I hate connecting through Roswell.”

“Just a mild case of the sniffles, she says.”

“I don’t care if he’s single-celled, he should have bought two seats.”

“This guy’s wife lets him drink on the plane!”

. . .

“Oh, now you want to talk, when all week it was ‘Do Not Disturb.’”

“Final warning, Mr. Weber. We don’t take kindly to shampoo thieves.”

“I can fluff your pillow the easy way or the hard way.”

“The time is 11:59. You have one minute to check out.”

. . .

“On what planet do you imagine this would be funny?”

“Lemme put it this way — when it comes to funny, me and you don’t see eye to eye.”

“It would work better with an alien.”

“It’s just not funny if she looks so sexy.”

. . .

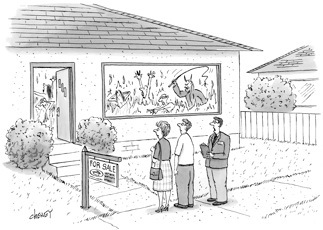

“The seller is extremely motivated.”

“According to the listing, there’s also a full basement.”

“The heating system is pretty old but very reliable.”

“I strongly recommend that you read the fine print on this one.”

. . .

If the judges at the New Yorker are to be believed, in each instance above you’ve encountered, amid the glorious sounds of three Stradivarius instruments, the raw bleat of a kazoo. You spied a set of rings finely crafted by Tiffany, Cartier, and Harry Winston, to which I contributed a cigar band. Below each cartoon are three sweet flowers, plus a sprig of crabgrass from yours truly.

OK, I’ll stop now and proceed to the question:

Can you tell in each instance which is the dud caption?

Isn’t it obvious?

No? You say . . . no?

Oh, thus am I vindicated, and bitter no more.

______________

Answer: In each set of four captions, the winner as selected by the New Yorker is first, my own rejected entry second, and the two non-winning finalists third and fourth.