.

.

There is no reason to believe Teju Cole intended his debut novel to present a challenge to reviewers, but that is what “Open City” does. The only way a critic can genuinely convey the force of this book — its full weight and effect — is to break a covenant with the potential reader by entering the forbidden territory of the spoiler, by revealing the specific shock that hits you like a block of concrete when you reach the novel’s final pages. No responsible critic will do that (nor will I).

Instead, you are apt to come across a positive reviewer of “Open City” saying the novel is, in some non-specific way, a “tour de force.” Another will cagily suggest something’s amiss by labeling the story’s narrator, Julius, a 32-year-old Nigerian-American who is completing a psychiatry fellowship in New York City, “an unreliable narrator.” I will put it this way: what this enormously talented writer has succeeded in doing is crafting a multi-layered reading experience that, at the book’s close, will redouble your receipt of its literary rewards. “Open City” is a novel you will be dying to talk about with other readers.

Since Cole is a newcomer, reviewers are falling over themselves trying to position him next to some veteran. Which writer will Cole remind the reader of? Candidates are piling up. One is Joseph O’Neill, who, like Cole, is a writer of mixed parentage, multicultural perspective, and author of a novel, “Netherland,” which, like “Open City,” explores themes of displacement and anxiety in post-9/11 New York City. Another is Zadie Smith, who, like Cole, unabashedly tackles matters of race, class, the immigrant experience, and suppressed history that must not remain hidden.

W.G. Sebald has been mentioned as well, presumably for his erudition and a shared style of writing that is slow and meditative, seemingly without much of a plot, and dependent on the cumulative accretion of observations. Cole, however, is not a formal innovator like Sebald, and the reader may be relieved to learn Cole is a conventional technician, using standard-length sentences, paragraphs, and chapters. Albert Camus’ “The Stranger” also has been cited as a model. At first blush this makes some sense (Meursault and Julius, twin protagonists of anomie) but my view is if Cole is following Camus, a stronger influence is “The Fall,” with its restless, talkative confessor.

An author I’d place on the list of comparables is Elizabeth Hardwick. Cole shares Hardwick’s keen turn of mind, her love of music, and her unerring command of language. Cole today, as Hardwick two generations ago, understands the seductive attraction of the walkable streets of Manhattan. Their ears are tuned to the innumerable personal stories waiting to be heard. (Cole has said wanted “Open City” to show how New York City is “a space full of ghosts and unfinished psychological business.”) Finally, like Cole, Hardwick showed no fear in letting autobiography undergird her fiction, notably in “Sleepless Nights.”

And, to add one more plate to the table: I see resemblances to the methods of Roberto Bolano’s “By Night in Chile.” Although Bolano’s short novel uncovers different sins and belongs to an earlier time of stress in a foreign nation, it shares with “Open City” a narrator prone to non-stop outpouring of stories, of exquisitely observed morsels of experience. Both narrators, it could be said, are engaged in a sort of “talking cure,” on a path to revealed truth. In both novels readers may find the meandering style frustrating. A stream of consciousness leaves some cold. Yet in each story it all adds up, at last, to a devastating contemporary psychological portrait.

But enough. Let Teju Cole and “Open City” be what they want to be: each reader’s own discovery.

—–

Notes:

(1) A version of this review is posted on Amazon, here.

(2) Cole has created on Tumblr a page “for and about the the novel Open City” here. For readers of the book it is a worthwhile resource, it takes the place of informative footnotes that a book as dense with allusions as Open City cries out for. But at this point the Tumblr page is only a beginning toward a collection of helpful annotations (I hope Cole, or perhaps others, continue to add material).

(3) A short but revealing interview with Cole is found on the Goodreads site, here.

(4) Audio of a BBC interview of Cole is available here (scroll down the page to find the list of “Chapters” (Cole is interviewed in Chapter 3 which starts at 26:30). The author’s spoken eloquence matches his written eloquence:

“I have not written a book about 9/11. I have written a book about how New York has habitually been a place that very quickly tries to get past the past and move on into the future. And so for characters such as Julius who are highly sensitive to it, it becomes an extremely heavy space. It becomes a space that is full of ghosts and unfinished psychological business.”

“I just think the work of mourning is very important, and if you don’t mourn properly your progress afterwards is sort of artificial, because there are things you haven’t dealt with.”

“It’s about finding your part in the human chain. And saying you’re not the first and won’t be the last.”

(5) Let me mention a few things that bothered me about “Open City.” One is the episode in which Julius takes a four-week vacation to go to Brussels in search of his maternal grandmother (his “oma”), with who he has lost contact. Yet Julius makes no effort to locate her, but instead continues his wandering habits (apparently it never occurs to him to simply hire a local detective). Although it is his essential psychological state, Julius demontrates a woeful passivity that began to grate on me somewhat. He is little more than an “eye and ear,” buffeted by events and strangers’ importuning, emasculated, a milquetoast set upon by bullies and opportunists. There is a wonderful moment during the BBC interview (linked to in Note 4) at 37:45 to 38:30. A fellow interviewee on the program, the passionately engaged sociologist Amitai Etzioni, shows frustration when Cole calmly mentions the Native Americans who once flourished in NYC but now are gone. Etzioni confronts Cole: “You’re so neutral, you’re so cool.” Cole is gracious in response, conceding the point, and assuring Etzioni that when it comes to the depredations of the past, “Believe me, I can get very strident.” “Please do,” recommends Etzioni.

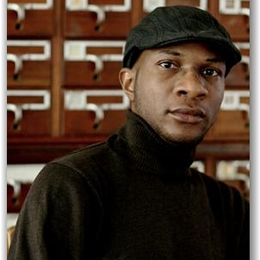

(6) I cannot help but like an author who chooses to be photographed, in the year 2011, in front of what has always been, for me, a comforting reminder of man’s durable commitment to preserving hard-earned knowledge. I’m speaking of something you can still come across in great old libraries: a massive, oak-drawered card-catalog.

.

.

UPDATE (05-12-2012): Just found a YouTube video of a recent interview with the author, here (video published May 8, 2012 by WNYC Radio). Responding to a question on the influence his photography has on his writing, Cole’s answer segues smoothly into a statement of purpose:

“One very particular influence is that photography inspires me to play with points of view, with actual physicals points, vantage points — to imagine a scene from above or from below. And so Open City is full of bird flights, people in skyscrapers looking down, people in planes, subways, wells. Because when you move up or you move down you actually change what you’re seeing — to defamiliarize the everyday.

“In photography and in writing, I want to give people the same sort of feeling, which is that there is someone else out there who’s noticing the small things of life, the things that are viewed obliquely, the things that deserve our attention but often elude our attention.”