.

.

It’s not easy to convey in the space of a short review a sense of the experience of reading Daniel Kehlmann’s “Fame.” In part this is because the author has packed into its 173 pages an ambitious set of themes and variations. Reviews appearing in magazines and newspapers that I read in recent weeks made me apprehensive about picking up a book described as “formally experimental” and “a post-modernist exercise.” What were the chances, I wondered, that this would turn out to be a pleasure?

High, I discovered.

Kehlmann has talent to burn. Even more important, he has an unselfish desire to communicate clearly with readers. In this, his sixth book, he brings together nine “episodes” that capture the feel of life in contemporary society. At the same time, Kehlmann offers canny reflections on the increasingly blurry boundaries between reality and fiction, truth and falsehood, the real and the unreal. He handles these subjects deftly, self-mockingly, and, by book’s end, poignantly.

In a nod to post-modernist “metafiction” fashion, a few of the book’s tales place front and center the slippery relationship between the author and his characters. In one story, for example, a character begs the author not to plot her demise. In another episode a young woman (an assistant to a famous writer) fears ending up as a mere character in one of his stories. This interplay of real and unreal is not new territory: consider Pirandello’s drama, “Six Characters in Search of an Author” and, in a different creative medium, the Hollywood movies “The Truman Show” (1998) and “Stranger Than Fiction” (2006). It’s a captivating device that remains fresh in the hands of Kehlmann.

There is a debate buzzing around “Fame” about whether it is a true novel, or a set of short stories, or something in between. If you are uncertain, as I was, about Kehlmann’s decision to construct a “novel” with no protagonist and with only weak threads connecting its nine tales, my advice is to remember that a similar structure undergirds the films “Short Cuts” (1993), “Pulp Fiction” (1994), “Amores Perros” (2000) and “Babel” (2006). If disjunctions and flights of philosophy of this sort leave you cold, then by all means avoid “Fame.” But if you found one or more of those movies great experiences, and if you are comfortable with the narrative methods of such authors as Paul Auster, Donald Barthelme and Robert Coover, then “Fame” will provide a sure platform for your enjoyment.

“Fame” is much more than just a literary experiment. I was pleasantly surprised by how varied and yet how conventional are its strengths. The stories are full of humor and pathos. In one, the course of an adulterous affair (an oft-told tale) is updated to include the intrusions of email, cell phones and instant messaging. The first minutes of awkward seduction are described thus: “I said we could go and find a drink somewhere, the old well-worn formula, and she, as if she didn’t understand or as if I didn’t know she understood perfectly well, or as if she didn’t know I knew, said yes, let’s.” Three of the book’s characters are authors, and this allows Kehlmann to knowingly track the shifting role of the writer in contemporary society. The vicissitudes of fame and the enigma of identity theft are explored. Keen insights abound: This is now “the age of the image, of the sounds of rhythms and a mystical dissolution into the eternal present–a religious ideal become reality through the power of technology.”

Appearing not once but twice is the Devil himself, and on both occasions he brings to the proceedings a jolt of guilty pleasure. Spying a mobile phone, the Devil notes: “Life is over so quickly — that’s what these little phones are for, that’s why we have all that electrical gadgetry in our pockets.” Yet technology has also meant dislocation:

“How strange that technology has brought us into a world where there are no fixed places anymore. You speak out of nowhere, you can be anywhere, and because nothing can be checked, anything you choose to imagine is, at bottom, true. If no one can prove to me where I am, if I myself am not absolutely certain, where is the court that can adjudicate these things? Real places anchored in space existed before we have little walkie-talkies and wrote letters that arrived in the same second they were dispatched.”

The soul-sapping environment of today’s corporate offices and off-site conferences is sharply rendered: “People cannot work together without hating one another”. In most of the tales, disappointment and bitterness break to the surface, yet one story ends, magically and lyrically, with a sweet salvation.

A character named Leo Richter, a writer, is my candidate for hero of the book. Undoubtedly meant to serve as Kehlmann’s alter ego, Richter appears in the second, third, seventh and ninth episodes. He’s a terrific creation: funny, ruminative, mesmerized by the creative process, wise, and able to rise to the occasion. The reader is not shown much of Richter’s writing and so we are hard pressed to judge its quality, but I suspect it’s like Kehlmann’s, which is very fine indeed.

– – – – – –

An abbreviated version of this book review appears on Amanzon.com, here.

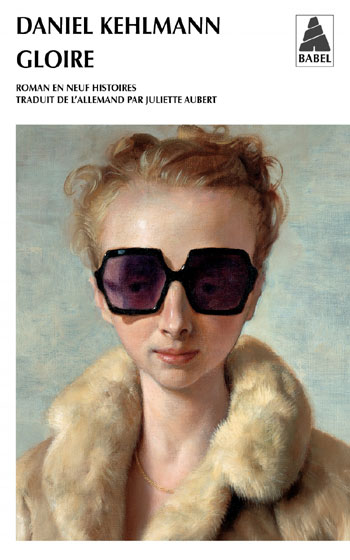

Below is the French edition of “Fame”. It features on its cover a typically strange portrait (“Rachel in Fur,” 2002) by the contemporary American painter John Currin .

.

.