In the preface to his book of essays, “L’Envers et L’Endroit” (“The Wrong Side and the Right Side,” 1958), Albert Camus wrote:

I know this with sure and certain knowledge: a man’s work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.

Most people cannot claim the mantle of artist. Still, most of us face the same urge to recapture early joys. This is sometimes disparagingly referred to as “reliving your childhood.” You see it at baseball games, where old men sit in the stands vicariously joining in the play on the field. You see it when a new mother selects a first doll for her daughter. You saw it last year when many Americans who, 40 years before, had joined Robert F. Kennedy in his improbable and sadly aborted 100-day quest for the Presidency, found themselves rejuvenated by another political campaign powered by hope and renewal.

I love snow for a simple reason: it instantly transports me back to childhood. To capture that feeling and make it available in every season, I collect art depicting snow in the city. One of the pieces in my collection is this 10-by-12 inch oil sketch, “Drifting Snow,” dated 1910, of an intersection in Philadelphia:

The artist, James A. Jefferys, lived in the city’s Manayunk neighborhood. He indicated the scene’s location in a hand-written inscription on the verso: “Drifting Snow. Sketched from 2nd floor front Room of H.D. Richards showing R.R. Gate Tender at Cresson & Short Leverings St Manayunk Phila 2-14-1910 By James A. Jefferys [?]20 Grape St”. To 21st century eyes, the picture’s most interesting detail may be the train engine entering from the right. There’s something odd about this vision of a train encroaching on an urban streetscape normally reserved for less daunting vehicles. It puts me in a surrealistic mood. I’m ready to imagine the train’s next stop is someone’s living room, as recorded in Magritte’s painting, “Time Transfixed.”

Historical notes: In 1929-1930, Reading Railroad replaced the Cresson Street train tracks with an elevated structure. The name Manayunk is derived from the Lenape Indian word “manaiung“, which means “river” or “where we go for drink.” Manayunk is an old blue-collar industrial neighborhood (textile and paper mills thrived in the 19th century) currently undergoing gentrification. It rises from the banks of the Schuylkill upriver from Wissahicken Creek, a few miles from center-city Philadelphia.

As for the artist, a Google search uncovered only sparse information about James Jefferys’ presence in Manayunk. Geneology sites contain references that supply birth and death dates of 1889-1969 and show his continual presence in Philadelphia (interrupted by service in World War I). Yet I’ve found nothing about his activity as a painter; no records of his artistic training, exhibitions, or awards. Possibly he was a self-taught artist. The 1910 painting shows a careful but tentative hand of a novice painter (he was only 21 at the time) uninfluenced by academic training. He kept painting, though. Possibly he worked in a related field such as sign-making, illustration, advertising or publishing. This early sketch reveals an intuitive sense of atmosphere and color. To my taste the painting is pleasing and very American.

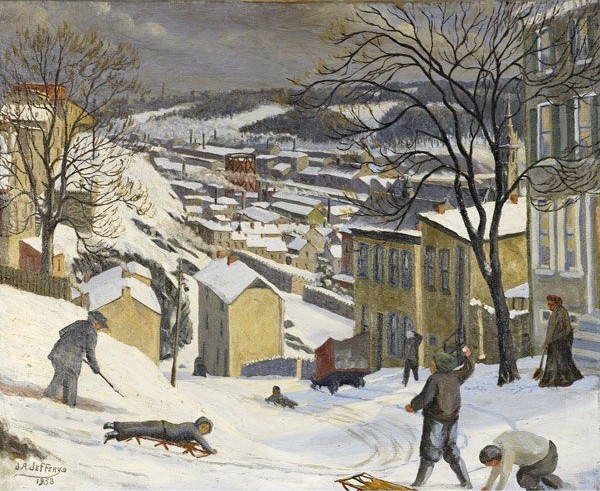

Three years after buying the snow sketch I came across, at auction, another painting by Jefferys that I thought would be a fine addition to the collection. I was happy to place the winning bid for this 1938 oil on canvas:

[Boone and Grape Streets, Manayunk, oil on canvas, 1938, 20 x 24 inches, signed and dated lower left recto; inscribed on verso: “Boone & Grape Sts / J.A. Jefferys / 4310 Terrace ST / Myk PA”. Rago Arts and Auction Center, Lambertville, NJ, Fine Art Auction, May 15, 2008, Lot 226.]

Jefferys’ note on the verso of the smaller snow scene, done nearly three decades before this painting, placed his residence somewhere on Grape Street. This means he would have been very familiar with the street’s trecherous upper reaches, depicted here. The Terrace Street address listed on the back of the 1938 work places him just two short blocks from Boone and Grape. I imagine him walking out the front door of his modest row house one cold day during the Great Depression, turning left up Terrace Street. A few steps into his trek he thinks twice about whether to take a detour down the steep Cotton Street steps leading directly to Boone. He decides to keep on the safer sidewalk, on up to Grape Street, where he turns left to make the final trudge downhill to the intersection at Boone. There, in front of him, is a scene of immediate activity and distant calm. He is glad to have come upon something demanding to be captured on canvas.

What were Jefferys’ working methods as an artist? Did he do a pencil sketch then and there? Did he bring a camera? Or did he leave the house carrying a fresh canvas, easel, and plein air materials, instinctively knowing this would be a productive day?

If you stand at the same vantage point today, as you can do in absentia thanks to Google Maps Street View, it is clear Jefferys took some liberties with distant perspective, bending space to create a more thrilling atmosphere. That is what artists do.

Repeating elements seen in his 1910 sketch, the upper portion of the picture features mills and factories, the soft hills beyond the river, and finally a spacious wintry gray sky. But Jefferys’ talents have moved well beyond the primitive mode of 1910, now embracing a style similar to that of John Sloan and of a younger cohort of social realist painters who emerged in the 1930s. He has well captured in paint a landscape cushioned in white, the cold air alive. He introduces a stronger narrative. The foreground tableau is a tale of play and toil, where boys’ shouts compete with the muffled metalic scraping of shovels handled by the old man at left and old woman at right. Tiresome work is consigned to the margins, peripheral to the central energy of sledders, who evade a snowball fight and zoom like dare-devils deeper into the world.

I am struck by how the composition, whether by chance or intention, is so reminiscent of one of the most beloved paintings in art history, Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow.

In an interesting online essay entitled, “How Can We Be Composed?- Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow,” Nancy Huntting quotes from Eli Siegel’s commentary in Art as Composition:

“Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow is a picture that tells us, Everything can be composed. Lines can be composed. The general direction of the picture is at a slant, or diagonal; the trees are assertively vertical; there are horizontal lines with the snow. Varying white shapes differ and coalesce. Houses, as volumes, mingle with snow as weight, and with space. Birds are diagonal, vertical, horizontal. The immediate in the picture mingles with a various middle ground, and a spacious, rising, misty background. Here is reality’s plenty caught hold of by Bruegel and arranged.”

Siegel’s formal analysis helps explain why a painting is so arresting. But it forgets the power of the sentimental elements (using the “s” word in its non-pejorative sense) of a painting — elements which, to an opened heart, provide pleasures all their own.

___________________________________________

UPDATE (August 2009)

In the Comments section, below, you’ll find an email from the artist’s grandson, Jim Jefferys, who came across this blog posting and wrote to me in June, 2009. A few months later he sent along some photos and these additional information about his grandfather’s artistic efforts:

“The first picture is a snow scene with a chimney in center (oil on canvas, rather large – 36 inches square). This painting was to be given to the first male Jefferys in each generation. After me it goes to my son. … The painting I’m told was a fireplace that my great, great grandfather built when he came to this country. The building, after years and years of neglect, is the way my grand father saw it and painted it on a snowy day. A lot of his snow scenes were painted outdoors when it was snowing. My aunt can tell you he would take her as a little girl sledding in Manyunk, with oils, brushes and easel in tow. So, that’s the answer to your one question — he did paint in the snow.”

“The second picture is the old Mill inn in Hatboro PA. which still stands to this day. [Note: unfortunately, the JPEG file for this painting could not be opened.] I was born and raised in that area. This building is still there and even though it has had renovations it still looks the same. The painting (watercolor) was completed on the day I was born. It was given to my father the next day for him to hold for me. Third picture (oil on canvas) is of Valley Green in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia. The building still there today and looks the same. I used to go trout fishing there when I was 16 years of age. It was one of my father’s favorite pictures.”

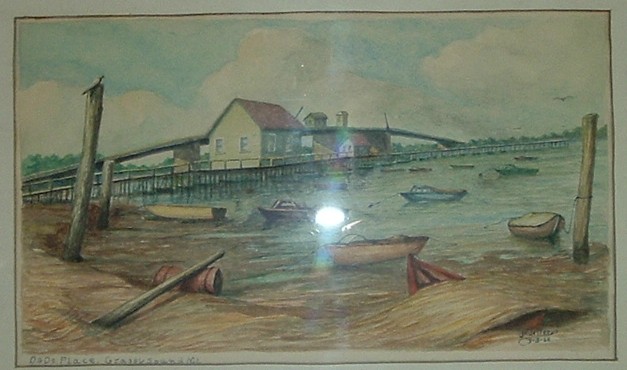

“Fourth picture [JPEG file was not openable] is a castle in Germany he did during WWI (oil on canvas). He also did a portrait of Von Hindenburg when he was there after Germany surrendered. That picture is around somewhere, as one of the relatives has it. Fifth picture [JPEG file not openable] is a small painting of a run-down farmhouse (oil on canvas). I don’t know anything about it, just that I liked it and my grandfather gave it to me after I graduated from high school. Sixth picture is a watercolor of Dad’s Place in North Wildwood, NJ. It is still there and I was with my grandfather when he started the painting , back when we did not have bug spray for green flies, etc. I asked for the painting and he gave it to me. He knew if he gave it to me I would not forget the good times I had going to the shore with him.”

“Seventh picture is down the shore somewhere, probably the same area, but this home is probably gone from storms now. It was a twin set (my sister has the other) and was painted the same summer as the Dad’s Place picture.”

.

UPDATE (September 2014)

Here are photos of a 1942 watercolor by the artist, depicting the church and rectory of Saint John the Baptist in Manayunk. These photos were provided to me recently by Rev. John J. Kelly (see Comments section) who found the picture in a back room of the rectory. He writes: “The painting is quite realistic and a fine depiction of Rector street. On the left is Saint John’s, two schools and the Church which still stands. On the Right is the Rectory which still stands; so too do the walls at the top of the street and on Rector street. It appears that the houses are all still intact. What is noticeably different is at the bottom of Rector street there is no high wall and SEPTA train tracks are missing from the painting.”

.

.

.

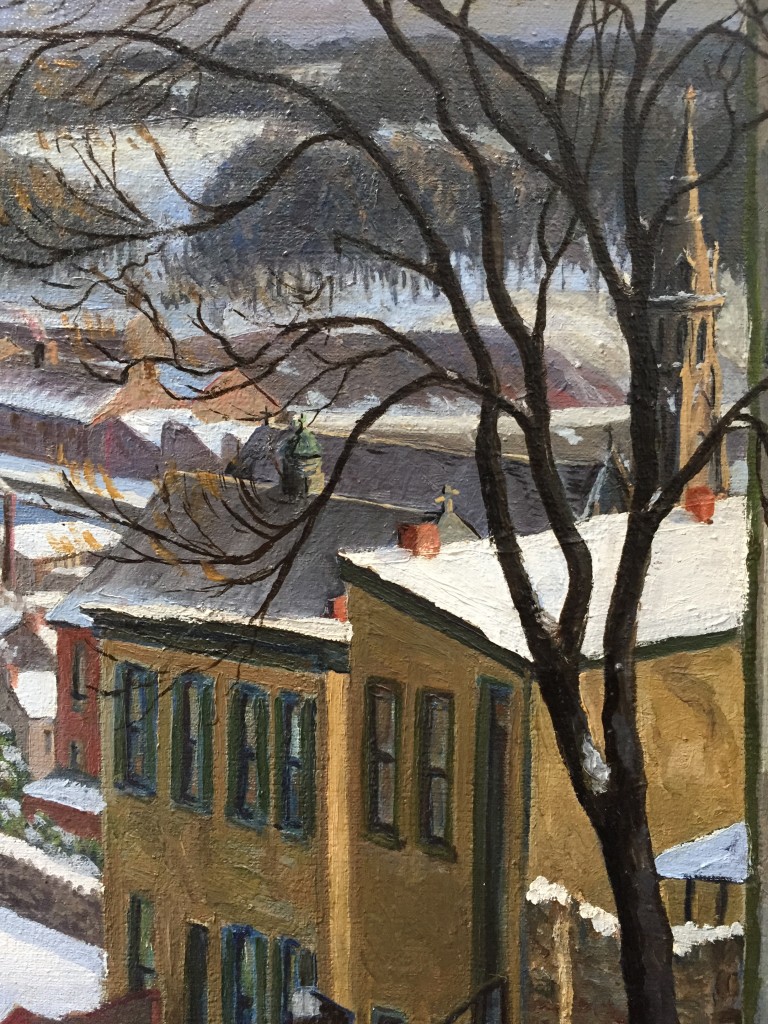

For comparison purposes, below is a detail of Jefferys’ 1938 painting, Boone and Grape St., Manayunk, showing the spire of Saint John the Baptist church and the roofs of two schools, from a higher perspective.

.

.

UPDATE – April 2015:

A new Google search for “James A. Jefferys” uncovered additional biographical information. The future artist was born in March of 1889 and died in July of 1969. The year 1938, when Jefferys painted the snow scene he titled Boone and Grape Street, Manayunk, shown at the beginning of this article, was a year of tragedy for the artist. In 1938 he lost both of his parents: (James Jefferys, 1851-1938) and mother (Anna Judge, 1864-1938).

The July 18, 1969 edition of the Des Moine Register newspaper published a short obituary for James A. Jefferys. It provides intriguing details about the artist’s early years:

“James A. Jefferys, 80, a portrait and landscape artist who painted European royally at the front during World War I, [died] in Philadelphia. He painted portraits of King Albert of Belgium and the Prince of Wales and later Edward VIII when they visited the front. He also made pen and brush sketches of battles.”