.

.

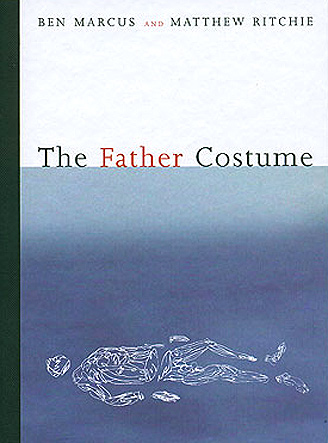

This novella by Ben Marcus (with illustrations by the artist Matthew Ritchie) is currently unavailable except from a handful of used book dealers who are selling copies at forbidding prices. What a shame.

The Father Costume was published in 2002 by Artspace Books as part of a series featuring “collaborations of image and text by today’s most innovative artists challenging the culture in which we live.” Here’s how Marcus describes his interaction with Richie:

We got together and talked a little bit about stuff that interested us. He’s really into physics and creation stories and origin theories of the universe, yet his relationship to all that heavy stuff is really light and playful and subversive. When you look at his paintings, there’s certainly nothing didactic or overbearing about them. He wants painting, essentially, to visualize the first moments of time. We threw some ideas around and decided to make a book. I wrote something and I showed it to him. He made some images and we got together again to mess around some more. There’s the book.

The book ought to be brought back into print, for the simple reason that I can think of no more exemplary introduction to the accomplishments of Ben Marcus, a so-called “experimental” writer who in these 45 pages belies that label’s negative implication of inscrutability by producing a work of deep emotion and resonance.

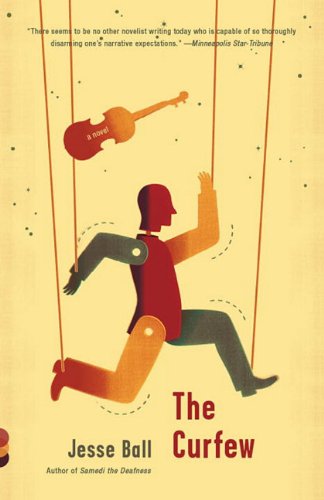

On the immediate level The Father Costume is a family drama told from the awed perspective of a child who attempts to follow the unfathomable actions of his father. It is narrated by one of two brothers removed by their father from their ancient home to escape some amorphous danger. They embark on a sea voyage that takes an ominous turn. As strange and at the same time as genuinely moving as Donald Barthelme’s affecting tale, The Dead Father (1975), the book bears an even closer kinship to Jesse Ball’s The Curfew (2011) which centers on the bond between a father and his daughter and is also set in a time and place not exactly of this world. Marcus previously examined relationships within nuclear families in Notable American Women: A Novel (2002) and does so again in the upcoming The Flame Alphabet (2012).

Veteran readers of Marcus know that the author achieves his signature brand of queasy disconnection and anxiety by means of language manipulation. He moves way beyond the relatively simple language games of Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky” (where nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs, are replaced with nonsense word counterparts) — upping the ante by constructing sentences with familiar but “wrong” words, crafting images and actions that catch you off guard. Early in the The Father Costume the son notes, for example, “I dotted our windowsills with listening utensils, in case a message came in the night.” The reader must remain nimble in order to negotiate the uncertain ride of these games. What serves you best in this mythical and fantastical universe is a comfort level with surrealism and a willingness to tap into your intuitive side. As well you must also accept Marcus’ obsession over certain objects (here, cloth, costumes, lenses), rituals, and failures of communication. Early on the son explains, “I could not read fabric. I had a language problem.” He notes that “the antenna of our radio had been soaking in honey overnight.” Later he confesses, “My brother and I would have attacked my father with chopping motions until he had been silenced. Keeping maybe his hair, just in case.”

Some of this oddness is amusing, but all sense of playfulness disappears as the story reaches its climax with violence and death. That is when essential questions are unavoidable. What is the meaning of the cryptically-described “costumes” the father makes for himself and his sons? Are these their personas? Socially-imposed behaviors? God’s constraints? Can The Father Costume be viewed as a religious allegory, and a specifically Christian one? At the end of the story the surviving son wonders whether “there may be a father operating on the other side of the glass.” In an interview C. B. Smith conducted with Marcus devoted solely to The Father Costume the author explains: “The narrator has no idea what is really happening. That kind of innocence appealed to me, the trust you put in someone whose designs are beyond your comprehension.”

More telling to me is how in the final pages the narrator finds solace in reviewing his martyred brother’s voice: “And though I do not understand the words, I enjoy their defeat of silence . . . I know them to be the right ones, the ones that someone had to say. I am happy that they are mine now.”

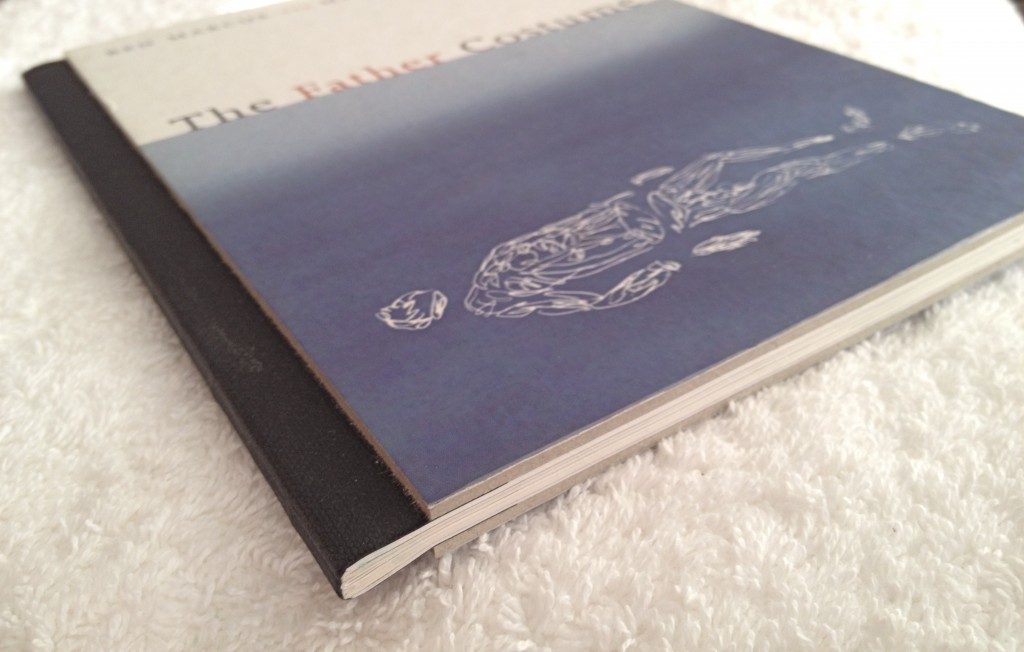

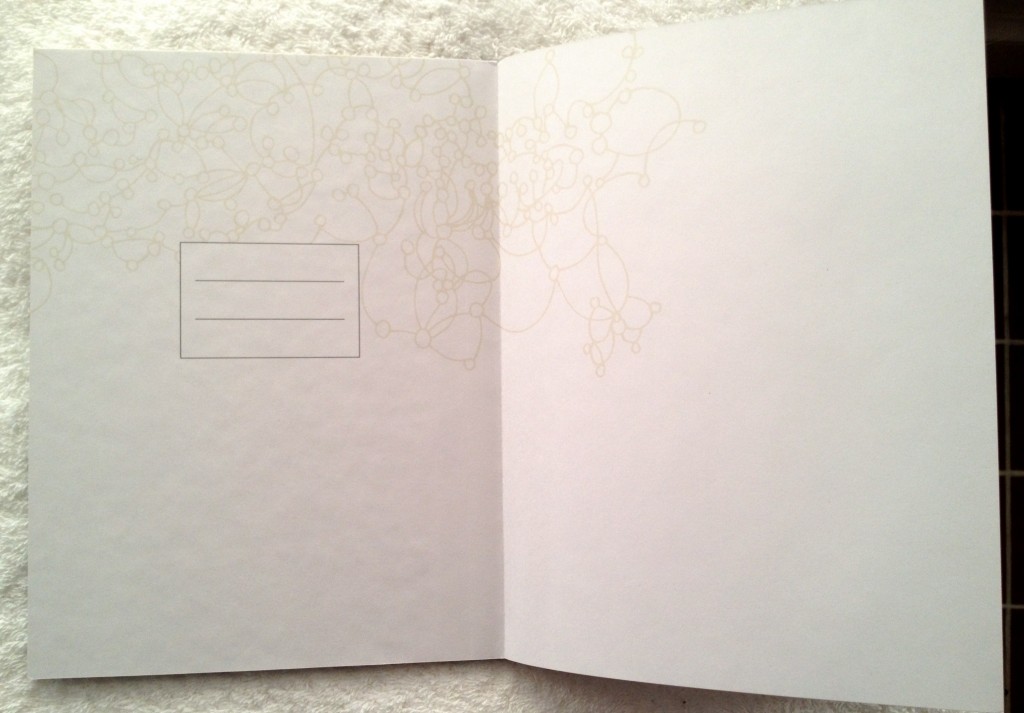

A few words on the book as a physical object. Fascinating to me is the book designer’s decision to take cues from childrens books of an earlier age. This includes retro 1950s-style thick cardboard covers whose edges are cut to expose gray paper pulp, as if this were much-handled book. Adding to the worn look is a spine wrapped in black cloth tape, as if Dad had repaired the falling apart pages with a trusty spool of old-style electrical tape. Inside the front cover is a place inviting the young owner to fill in his or her name in clumsy block letters. All of this adds a sense of innocence to a challengingly adult book.

.

.

.

.