.

.

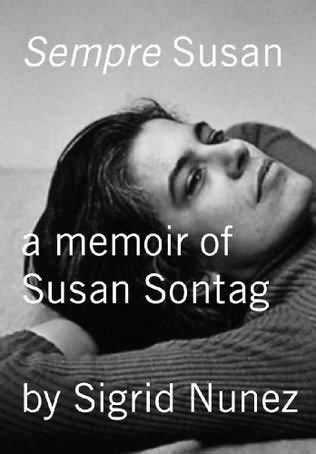

In her short novel, “Mitz” (1998), Sigrid Nunez imagines the experiences of a pet marmoset who became an affectionate companion to writer and editor Leonard Woolf, husband of novelist Virginia Woolf. During the course of the story, little Mitz takes on the role of eye-witness to the ups and downs of the couple’s Bloomsbury household during the period when Virginia descended into depression. Based on actual events (Leonard really did own a marmoset in the mid- to late-1930s), the book is enlivened by the author’s imaginative scene-setting, and her exploration of a three-pointed relationship, sadly destined to last but a few years.

I read “Mitz” a year ago and reviewed it positively, here. I still remember the pleasure of its warm tone and modest charms. Within a slim frame, “Mitz” accomplishes many things. It is a playful writer’s holiday; a recreation of a time and place in history; and a deft exercise in stagecraft as the author directs the movement of significant personalities, among them T.S. Eliot, John Maynard Keynes, and Vita Sackville-West, as they intersect with the era’s quintessential literary power couple — a duo known affectionately among friends, and referred to none too kindly by enemies, as “the Woolves.” In Nunez’ hands, “Mitz” becomes a window into a storied household and the quotidian pleasures — reading, writing, eating, talking — sheltered therein. Nunez’ touch is light as air as she anatomizes domesticity via the device of a domesticated (well, mostly domesticated) pet. The book charts the breathing in and breathing out of a successful marriage. It offers lessons in patience and protectiveness and love.

CLOSER TO HOME

Now Nunez has written another story of a three-way relationship. The just-released “Sempre Susan: a Memoir of Susan Sontag” and “Mitz” both weigh in at about 130 pages. This time, however, the author has a long-simmering personal agenda to get through — and a volatile mix of objectives to achieve. That Nunez somehow pulls this off, and in such short order, is a testament to her talents as a writer.

In “Sempre Susan” Nunez reminisces about her experience at the start of her writing career when, for a brief period starting in 1976, she lived and worked in the household shared by the older and notorious writer Susan Sontag and her son, Philip Rieff. The relationship that developed took the form of an unstable triad, a love/hate triangle. Inside Sontag’s apartment, Nunez shared a bedroom with David, who had become Nunez’ boyfriend soon after Nunez arrived at the apartment on an assignment to assist Sontag in managing her correspondence. Nunez reveals how Sontag treated David more like a brother or best friend than her son, and it was not long before a tense current encircled the three. The travails of this arrangement, Nunez writes, were aggravated by Sontag’s mental instability.

The first hundred pages of “Sempre Susan” are filled with observations about Sontag’s strong character. Her quirks were legion. She felt alive only in the city and lacked any appreciation for nature. She had never heard of a dragonfly. She wore a men’s cologne, Dior Homme. At the cinema she always sat in the first row. Her favorite words were: servile, boring, exemplary, serious, grotesque. Her credo: “Security over freedom is a deplorable choice.” She had, Nunez comments with what I take to be approval, “the habits and the aura of a student all her life.”

The reader is never far from another anecdote involving New York literary life as luminaries pass within Sontag’s orbit (Joseph Brodsky, Elizabeth Hardwick, Jean Genet). Her love life gets full attention. Nunez reports her resigned observation: “Mean, smart men and silly women seem to be my fate.” Nunez pays attention to how Sontag managed the challenge of a being a female writer — and, even more dangerous, an intellectual — in the second half of 20th century America.

ROUGH JUDGMENTS

In the early pages of the book the thrust of Nunez’s cuts may be unkind (for example, at one point she notes how Sontag usually dressed like a “prison matron”) but her commentary is not vicious. Yes, Sontag had a high-maintenance personality, and so what? Nunez still conveys a modicum of respect for her teacher and the advice she dispensed, albeit commandingly. For instance:

“[Sontag] also believed that how other people treated you was, if not wholly, mostly within your control, and she was always after me to take that control. ‘Stop letting people bully you,’ she would bully you.” (p. 72.)

Though the irony may mask hurt, Nunez’ temper remains jocular. And even as you pass the halfway mark the author is still expressing appreciation for what Sontag gave to her, even down to the transfer of mundane habits:

“Because of her, I began writing my name in each new book I acquired. I began clipping articles from newspapers and magazines and filing them in various books. Like her, I always read with a pencil in hand (never a pen), for underlining.” (p. 85.)

Then things change, abruptly. As the pile of anecdotes grows higher, you begin to perceive a growing tension between mentor and protégé. In the book’s final third, magnanimity departs. Long-harbored resentments are let lose. You can almost hear the snap! of a breakthrough epiphany, as in a therapy session, when Nunez specifically recalls —

“[Sontag] reminded me to a remarkable degree of my German mother — another touchy, chronic ranter who thought she was surrounded by idiots, who practically lived in a state of indignation, and who happened also to share Susan’s contempt for American superficiality and American ‘culture.’” (p. 96.)

And so, for the remainder of the book, the text is overtaken by Nunez’ blunt, relentless portrait of a sick woman, a person oblivious to the feelings of others, a monster. Nunez reports that, as a mother to Philip, Sontag was an idiot from the get-go: “From the time she knew she was pregnant until the day she went into labor, she never saw a doctor. ‘I didn’t know you were supposed to.’” (p. 103.) Nunez’s rough judgments are swift and stark: Sontag was depressed (p. 114), paranoid (p. 115), narcissistic (p. 116). She was, in the final analysis, “a masochist and a sadist” (p. 118.)

AS FIRST INTRODUCED IN THE NY TIMES

Some readers may be attracted to “Sempre Susan” after having read an excerpt published in the New York Times’ Style Magazine (February 25, 2011). That article, titled, “Suddenly Susan,” carried the tag line: “When the author shacked up with Susan Sontag’s son and his brainy mom, in 1976, three was not company.” If that was your initial experience with the book, please know this: What you read was misleading. The material may have struck you as mildly critical of Sontag, mildly bitchy in tone, mildly voyeuristic. Some readers who posted comments online have said as much. And here’s how the magazine’s editor, Sally Singer, described its appeal:

“I want a good, sexy, neurotic story about New York literary life in the Seventies. I want the New York Review of Book parties. I want a little Farrar, Strauss and Giroux. You have that literary dream of New York. It’s got it all.”

But what Singer edited, for placement in the New York Times, was not representative of the content and tone of the actual book released to the public this month. True to its code (constraining the “Gray Lady” to print only what’s “fit”) the New York Times altered Nunez’ text for its readership. Whether this was accomplished with Nunez’s input and approval is not clear. The material published in the Times’ Style Magazine is described not as an “excerpt” but instead as a new product “adapted from” the book.

To give an example of the alterations, consider how Nunez herself treats the salacious rumor of incest between Susan Sontag and Philip Rieff:

“That there was feverish, prurient interest swirling around 340 [the address on Riverside Drive of Sontag’s apartment] was something I already knew. Before I ever met Susan or David, I’d heard the talk. Now people came straight out and asked: Is it true? Have they had sex together? Sometimes, rather than being asked, I was told: They must have had sex together.” (p. 100)

Here, as throughout the book, Nunez uses her skills as a novelist to lead the reader toward a tentative — if still uncertain — conclusion. In the pages leading up to that point she has built the platform from which to launch her heaviest character assaults. She has offered vignettes of Sontag’s disdain for convention (“What did it matter what other people said?”), her outlaw instincts, her transgressive behaviors. Then, as the reader absorbs the implications of Nunez’ flat presentation of the rumor of incest, Nunez simply moves on to other aspects of Sontag’s foul reputation. Nunez neither confirms nor denies the rumor, leaving the reader exactly . . . where?

Compare how the New York Times handles the text:

“Before I ever met Susan or David, I’d heard the talk. Now people came straight out and asked the absurd: Is it true? Have they had sex together?”

With the clarifying addition of two words — the thing some ugly people were wallowing in was the absurd — the editor steers the reader away from the rumor. Pay it no heed, consign it to the category of lies. A question you might have for the author is: Which of the two presentations is preferred?

THE “MEMOIR DEFENSE” OF OFFENSE

Then there is the question of the reliability of Nunez’ memories. Rare is the page of “Sempre Susan” that lacks one or more quotations from the mouth of the loquacious Sontag. Presented as transcribed conversations, Sontag’s words add punch to the proceedings. But consider: most of these are words Sontag uttered 35 years ago, and they are not commonplaces, not throwaway lines, but language with exactness, with pungency, with meaning. In short, character-defining utterances, down to their last nuance. These “quotations” are the material Nunez leverages to construct her brief against Sontag. Yet, as Nunez confesses early in the book, she kept no contemporaneous notes: “I didn’t keep a journal then — or if I did, it has long since vanished.” (p. 24). How, then, can the reader have confidence in the accuracy of her reconstructed conversations? Is Nunez’ memory of conversations supported by contemporaneous letters, notes, journals kept by Sontag herself, or by David Rieff? Did Nunez review that related material as part of her research and fact-checking? Does “Sempre Susan” conform to professional and ethical standards of journalism, biography, history writing? Should we expect it to? Does the book’s presentation as a “memoir” shield it from those norms?

Some will argue a “memoir,” especially one from the imaginative mind of an author whose métier is the novel (Nunez has published six novels; this is her first published book of non-fiction), ought to be evaluated through a different lens. But even if that were the case, shouldn’t the author at least provide us with contextual support. How about an Introduction, an Afterward, an Acknowledgments page, or a section of Notes explaining and supporting the book’s content? Nothing of the sort accompanies “Sempre Susan.” Regrettably, at its close, the book simply peters out. There is a final expression of disappointment, a sigh of self-pity, and nothing more.

The reader is apt to remember how, earlier in the book, Sontag admonished her then assistant and future profiler: Stop letting people bully you! A reader inclined to armchair psychologizing may very well recognize the defensive posture Nunez adopts, a classic passive-aggressive mode. Consider, for example, this admission:

“But, to be honest, I often played dumb with Susan, and if there was one thing that could drive her insane, it was that.” (p. 131.)

I remembered the three-member household that Nunez lovingly recreated in “Mitz” (Leonard, Virginia and the marmoset) and how it was so alive, so charmed, so pleasurable. I — and I suspect the author as well — longed to trade places, if only for a moment, with the privileged position of that little resident-guest. In “Sempre Susan” Nunez often pauses to compare and contrast Sontag to Virginia Woolf, each time to Sontag’s detriment. With undisguised bitterness Nunez remembers Sontag referring to the trio — David, Susan and Nunez — as “the duke and duchess and duckling of Riverside Drive.” (p. 105.) Nunez knew the duckling part wasn’t good. She felt cheated.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

It is disappointing to realize how little “Sempre Susan” accomplishes. The missed opportunities are many.

Nunez, a serious and accomplished writer in her own right, offers few insights into Sontag’s writing. Although Nunez makes very clear her disdain for Sontag’s attempts at fiction, she offers no serious critical analysis of Sontag’s thought or ideas. She mentions but glossed over the themes and content of her ground-breaking essays. There is nothing about the genesis or evolution of Sontag’s political views during their years of intimacy. The reader searches in vain for Nunez to express an opinion on the question uppermost in many minds: Was Sontag a thinker of importance? You are left with the impression Nunez is simply not interested in the play of ideas that was the essence of Sontag’s breathing in and breathing out.

During the time Nunez lived with Reiff, Susan Sontag was assembling the essays that would become “On Photography” (1977). Although present “at the creation” of that seminal work, Nunez offers us nothing at all about its formation: only a single short paragraph mentions the book, and it is unenlightening. For many readers this will be frustrating. Nunez must have seen or overheard something of interest. If you are a reader who likes to learn about the “Eureka” moments that seize a creator, or who seeks the vicarious thrill of being a fly on the wall of the ugly but beautiful creative process, “Sempre Susan” will leave you starved. Famished too will be readers expecting to experience at least something of Sontag the intellectual, some glimpse into her mind at work. Is that not something those persons who were her assistants, and those who shared even greater intimacies, may provide to us? What, we ask, was the source of Sontag’s brilliance? What signs did you see? In response to the curious reader Nunez grants us silence.

FINAL THOUGHT: THE “WHY” OF THIS BOOK

I understand why Nunez wanted to — and needed to — write this book. The exercise was therapeutic, for sure. Nunez’ reminiscences — however flawed — also have potential value to history, if time grants Sontag status as a durable contributor to American literary and intellectual history. At their most basic, Nunez’s pages are evidence, are material to be sifted through critically by future biographers. Nunez’ memories will be joined by the remembrances of Sontag’s colleagues, friends, editors, and other intimates. I was happy to discover another former personal assistant to Sontag, Karla Eoff, has written a piece for the Winter 2011 edition of the online literary magazine, blipmagazine.com, here. In a very brief space, Eoff describes the creative process that produced Sontag’s celebrated novel, “The Volcano Lover.” Her account is valuable evidence. Yet another reminiscence by a former aide-de-camp, this one painfully revealing, especially on the subject of Sontag’s sexuality, is provided by Terry Castle, here.

If the writing and preservation of Nunez’ recollections has value, a separate question arises over whether the material should have been published at this time. My opinion, for what it’s worth, is that Nunez would have been better advised to have kept the completed manuscript of “Sempre Susan” under her lock and key. Or, she should have donated it to a suitable library for preservation and use by scholars (a good choice would have been UCLA Library which houses Sontag’s papers).

– – – – –

UPDATE: An adaptation of this review appears on Amazon, here.

.