.

.

As I write this post, “The Great Gatsby” ranks as #6 among all books Amazon’s best seller list. Ever since reading the book became a mandatory right of passage in most American high schools, it has remained a perennial best seller (and a fixture on Amazon’s Top 100 Books list), but the reason for the current heightened interest is the release of a new filmed version by Baz Luhrmann. Readers have been posting reviews of the book on Amazon at a frantic rate in recent weeks. A new statement of praise, or sometimes a discordant note, appears just about every two hours around the clock. Most of these amateur reviewers identify themselves as re-readers.

Me, too.

My thoughts?

It’s not The Great American Novel. That laurel ought to be reserved for a novel of largeness and sprawl — a book that’s brawny, not slender; loud, not languid. There are candidates other than “Gatsby” that have a superior claim on the label.

It was Hemingway’s opinion that “all modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.” What Hemingway didn’t realize when he rendered that judgment in 1934 was that “The Great Gatsby,” which had been released less than a decade before to positive critical reaction but disappointing sales, was even then steadily gaining an appreciative audience among common readers. And for later generations of writers, the book was about to exert an influence far beyond its weight class.

When I opened up “The Great Gatsby” once again, this time in middle age, I was impressed by how securely the novel belongs to the ongoing current of American literature. With the assistance of related sources of commentary on the novel, I also came to understand just how seriously the well-read Fitzgerald took literature’s calling and his own role within its tradition.

T.S. Eliot’s influence on the author of The Great Gatsby

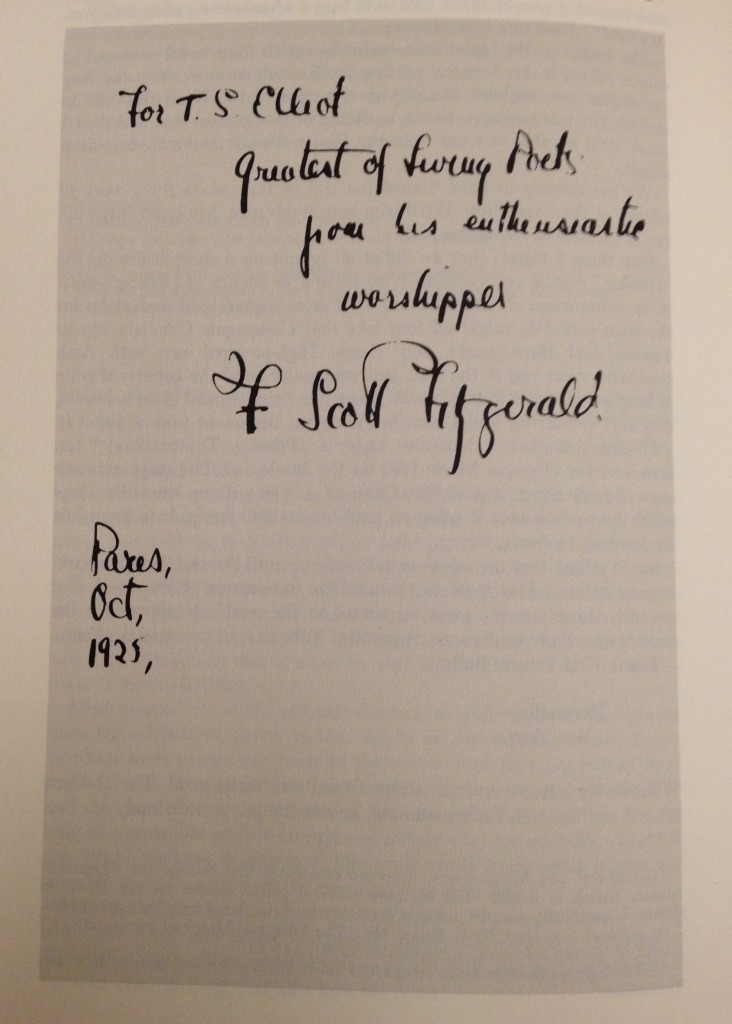

Fitzgerald, I learned, was a self-described “enthusiastic worshipper” of T.S. Eliot. He referred to Eliot as “the greatest of living poets” when inscribing a presentation copy of “Gatsby” to him in 1925:

.

.

The respect was mutual. After reading “Gatsby,” Eliot wrote Fitzgerald to say the novel “seems to me to be the first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James.”

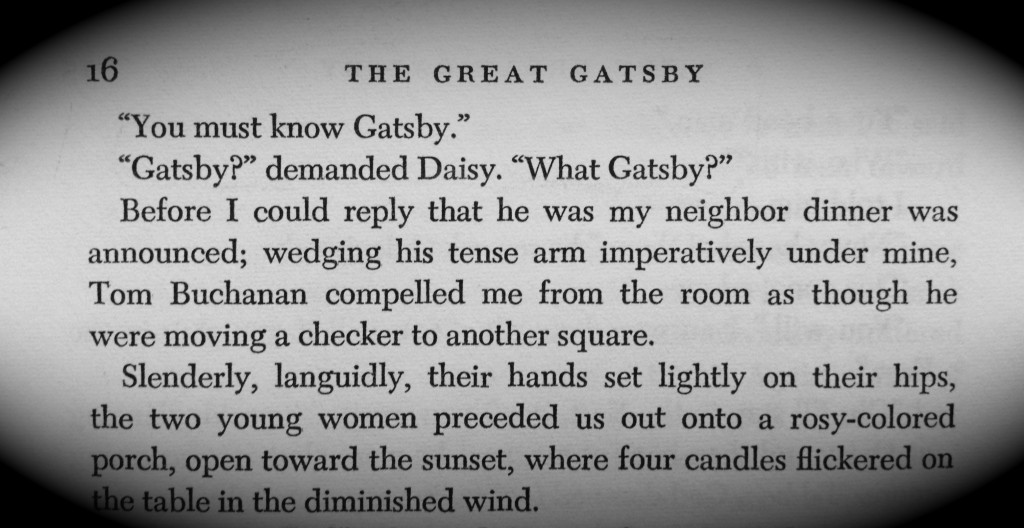

I was struck on several occasions by how much of Nick Carraway’s character and behavior fits the mold of the narrator of “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” Nick is glad to be of use to Daisy and Gatsby. His attachment to Gatsby may well be described as that of an attendant Lord, whose actions are deferential, politic, cautious, a bit obtuse. In the end Nick recognizes himself as, perhaps, the Fool. There are details in the novel that borrow generously from the poem. For example, when observing feminine beauty, Nick is as attentive to slender, languidly-posed ladies as his English counterpart. Compare Prufrock (“I have known the arms already, known them all–arms that are braceleted and white and bare [but in the lamplight, downed with light brown hair!]”) with Nick’s observation of Myrtle’s sister Catherine, whose “bracelets jingled up and down upon her arms”).

Nick’s perambulation of Manhattan in Chapter 3 (“At the enchanted metropolitan twilight I felt a haunting loneliness sometimes, and felt it in others–poor young clerks who loitered in front of windows”) is a variation on Prufrock’s penchant for wandering at dusk through narrow streets to watch lonely men in shirt-sleeves, leaning out of windows.

Prufrock’s seaside romantic fantasy (“I shall wear white flannel trousers, and walk upon the beach. I have heard the mermaids singing, each to each”) becomes Nick’s street-side daydream (“I liked to walk up Fifth Avenue and pick out romantic women from the crowd and imagine that in a few minutes I was going to enter into their lives”). These yearnings are unrequited. The mermaids will not sing to Prufrock, and Nick’s girls are equally elusive as they “faded through a door into warm darkness.”

So too does Fitzgerald’s animistic description of the breeze blowing through the sitting room of the Buchanan mansion in Chapter 1, and its gentle demise (“the caught wind died out about the room, and the curtains and the rugs and the two young women ballooned slowly to the floor”) appear to repeat the journey — and to adopt the anthropomorphic tenor — of Eliot’s fog and smoke that licked its tongue into the corners of the evening, slipped by the terrace … and curled once about the house, and fell asleep.

In Chapter 2 Fitzgerald identifies the Valley of Ashes past Flushing as the waste land — the very title Eliot gave to what would become his most celebrated poem. Eliot finished “The Waste Land” in 1922, the year in which the events described in Gatsby take place.

If Fitzgerald’s prose can be said to converse with his poetic contemporaries, the lasting glory of his prose is its power to continue the conversation with later generations of literary lions. “Gatsby,” it seems to me, has become for American writers a primary source, an unavoidably inspiring voice.

Williams, Miller, Updike, Salinger

When Daisy castigates Tom as “a brute of a man, a great, big, hulking physical specimen,” chances are good the reader will conjure up the showdowns between Blanche DuBois and Stanley Kowalski. When Nick, organizing the funeral, despairs over the coldheartedness of Gatsby’s friends and hangers-on (Nick’s devastating two words are: “Nobody came.”), the reader may be reminded of Willy Loman’s widow, Linda, during the Requiem scene that ends “Death of a Salesman,” as she expresses her pained confusion: “Why didn’t anybody come? Where are all the people he knew? Maybe they blame him.”

With alchemical dexterity Fitzgerald, in the opening chapter of “Gatsby,” transforms a ringing telephone into a living character capable of disordering a marriage — an audacity John Updike pays homage to in his short story of adultery, “Your Lover Just Called,” collected in “Museums & Women and Other Stories” (1972).

I was frankly surprised by the evident ties between “Gatsby” (1925) and another landmark in American writing that debuted a generation or so later — “The Catcher in the Rye” (1952). When speaking about American voices and memorable narrators, literary critics love to cite Holden Caulfield and Huckleberry Finn. The reader is introduced to those two indelible characters as they pursue a wayward path toward maturity, shedding innocence along the way. Yet I find there is also a kinship between Holden and Nick Carraway. Although Nick is older (29 going on 30 over the course of the story he narrates), he is in many ways just as unanchored as Holden, or Huck for that matter. Each is a person whose education is not yet complete, a persona still in formation.

Both “Catcher” and “Gatsby” use the framing device of a narrator who has escaped the scene of an intensely personal experience. What Nick describes as his own “riotous excursions with privileged glimpses into the human heart” during the summer of 1922 could, with some tailoring, fit the days Holden describes for us (what he calls “this madman stuff that happened to me around last Christmas”). Both characters are now recovering from trauma and are relaying their tales from a safely distant post. Notably, in Baz Lurhmann’s re-telling, Nick has not returned home to the middle west (as in the novel) but instead finds himself, like Holden, in a California sanitarium.

Holden (in Chapter 24) and Nick (after the drunken party in Chapter 2) recount enigmatic but sexually-charged incidents with older men. Both Holden and Nick, toward the end of their stories, engage in small, symbolic acts to rid their world of indecency: Holden erases an obscene graffiti in the stairwell of his sister Phoebe’s school; Nick scrapes away an obscene word a truant scrawled on the steps of his friend Gatsby’s mansion.

More than nostalgia: “the colossal vitality of illusion”

My appreciation of Fitzgerald’s novel has been abetted by reading letters to and from the author, collected in the “Correspondence of F. Scott Fitzgerald” (1980), edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli and Margaret M. Duggan. In a 1925 letter to Scott, Roger Burlingame, an editor at Scribners and fellow novelist, observed:

“Someone once said that the thing that was common to all real works of art was a nostalgic quality, often indefinable, not specific. If that is so then The Great Gatsby if surely one because it makes me want to be back somewhere as much, I think, as anything I’ve ever read.”

Yet there is so much more that is durable about “Gatsby” than mere nostalgia, or why would its final sentence (“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past”) have become indelibly linked to our vision of America? One of the pleasures of re-reading the novel is to discover how carefully, how relentlessly, the author prepares us for that final revelation.

From the beginning the seeds are planted with rueful words about “the abortive sorrows and short-winded elations of men” (p. 8). Then come the author’s tossed off psychological insights about his main characters. Tom, for example, is “forever seeking, a little wistfully, for the dramatic turbulence of some irrecoverable football game.”

Hints of the what will become the ultimate phraseology (borne back, past, beat on) start to appear. At the riotous party in Chapter 3 (p. 48), “girls were swooning backward playfully into men’s arms […] knowing that someone would arrest their falls — but no one swooned backward on Gatsby.” Gatsby declares: “I’m going to fix everything just the way it was before” (p. 99). Later, when the principal characters assemble at the Buchanan mansion on a sultry afternoon, Daisy’s voice “struggled on through the heat, beating against it” (p. 106). An hour later, the cast of five reassemble in a steaming Manhattan hotel room. Gatsby realizes he is losing Daisy, “and only the dead dream fought on as the afternoon slipped away, trying to touch what was no longer tangible, struggling […] toward that lost voice across the room.” (p. 120). Still later, as Nick and Jordan drive back to Long Island, a single sentence breaks off to becomes a separate paragraph:

“So we drove on toward death through the cooling twilight.”

The tragic power of receding time is alluded to yet again when Gatsby, on the day of his death, tells Nick the history of his relationship with Daisy. After returning from the war, Gatsby learns Daisy has married Tom, yet he is compelled to take a “miserable but irresistible” journey to Louisville, the city where the two first met:

“[Gatsby] stretched out his hand desperately as if to snatch only a wisp of air, to save a fragment of the spot she had made lovely for him. But it was all going by too fast now for his blurred eyes and he knew that he had lost that part of it, the freshest and the best, forever.” (p. 135)

The adjective you most frequently encounter in the text? Romantic and its variants.

.