.

In which the author speculates that the compositional inspiration for Eanger Irving Couse’s controversial American Western painting may have been an East Coast work by Winslow Homer

.

.

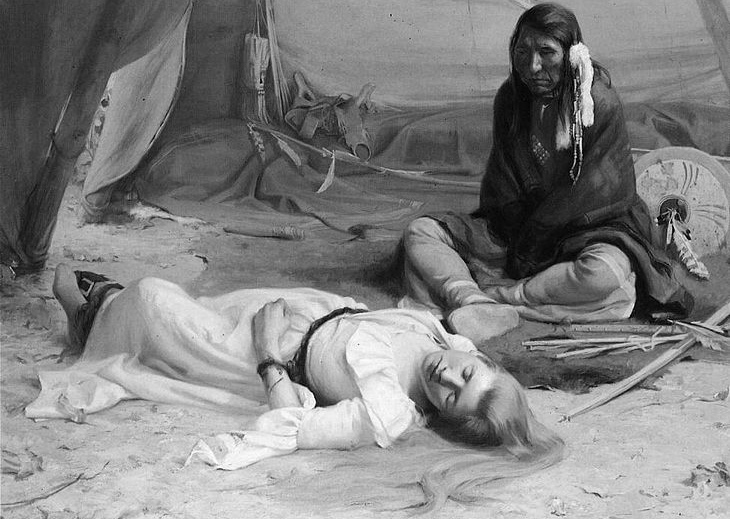

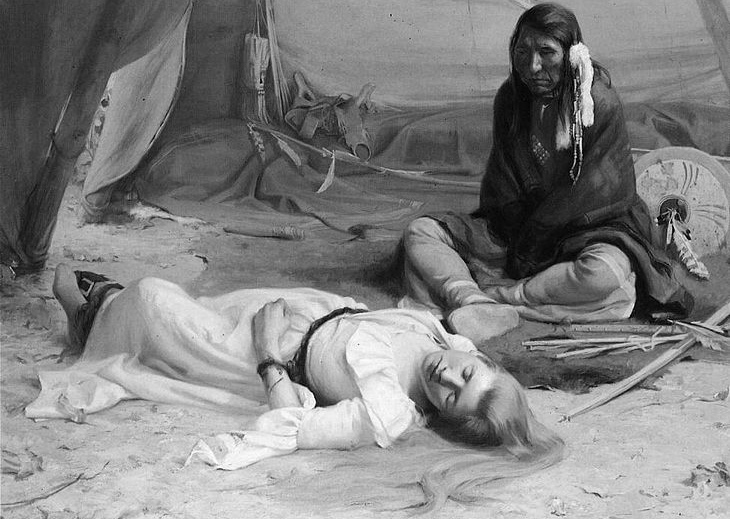

The Captive is a large studio work completed early in the career of the American artist, Eanger Irving Couse (1866-1936). Shown at the artist’s first solo exhibition held at the Portland (Oregon) Art Association in 1891 where it garnered much attention, the work was exhibited shortly thereafter at the Paris Salon of 1892. The Captive is significant as the first Native American subject attempted by and artist who would go on to achieve fame in the United States for his paintings of the indigenous inhabitants of New Mexico. The Captive is now in the collection of the Phoenix Art Museum.

This is a “staged” picture, to be sure. Yet the narrative suggested by The Captive is rooted in historical fact. The background story involves a raid conducted by the Cayuse Indians in 1847 upon a mission settlement of white immigrants in the Oregon Territory. The incident culminated with the capture of a woman, a 17-year-old school teacher named Lorinda Bewly, whom Cayuse chief Five Crows wanted to keep as a wife. The young woman refused his offer, and after two weeks she was put up for ransom. The ransom was paid by the British at Fort Vancouver.

Wikimedia Commons user Rob Ferguson, Jr., describes the setting imagined by Couse:

Couse’s painting shows us a dramatic scene – Lorinda is lying on the floor of the chief’s teepee, unconscious, with bloody bonds testifying to a terrified but courageous struggle. Five Crows is seated on the floor, staring at her and unable to fathom her behavior, her aversion to him. Couse has shown us two cultures in tragic juxtaposition, and we are able perhaps to have an understanding of each.

It is reported that two women — Couse’s wife, a rancher’s daughter from Washington state, and a local Kickitata indian — served as the artist’s model for Lorinda.

From its earliest appearances before the public, The Captive generated discussion and controversy. According to a descriptive note attached to the Wikipedia Commons image of the painting, this notoriety arose in part from the picture’s “sexual implications (rather strong for the art of the period)” and at the same time its contradictory “stereotyping of Native Americans [and] ‘noble savage’ romanticization of them.”

In our own day, this controversy returned with renewed force when the work appeared in a 1991 art exhibition, The West as America: Reinterpreting Images of the Frontier, 1820–1920, organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum (known then as the National Museum of American Art). This ambitious show included a total of 164 works. Essays in the show’s catalog as well as the descriptive wall texts that visitors to the museum found next to each picture, sparked protests from a few historians who disputed the curatorial interpretation of artists’ meanings and intents. More noisily still, rebuke came from conservative politicians who condemned the exhibition for what they saw as its unrelieved leftist agenda.

An example of the material that incited critics is the wall label that accompanied The Captive (text written by William H. Truettner, Curator):

“From Puritan cultures onwards, the captivity theme had been an occasion for white writers and artists to advocate the “unnaturalness” of intermarriage between races. Couse’s painting is part of this tradition. The painting establishes two “romances.” The first – suggested but not denied – is between the woman and the Indian. The two figures belong to different worlds that cannot mix except by violence. (Note the blood on the woman’s left arm). The second romance is between the woman and the viewer of the painting, implicitly a white man, who is cast in the heroic role of rescuer. This relationship is the painting’s “natural” romance. These two conflicting romances account for the ironic combination of chastity and availability encoded by the woman’s body. The demure turn of her head shows that she has turned away from the Indian. Yet this very gesture of refusal is also a sign of her availability: she turns toward the viewer. It is by her role as sexual stereotype that the woman in Couse’s painting is really captive.”

I am not aware of any study or analysis by critics or art historians of the formal aspects of The Captive. This may be due to the overwhelming interest nowadays in matters racial, sexual, social and political. In particular, I have yet to find any mention of the sources or inspirations for Couse’s composition or the details he chose to emphasize. If, as seems likely, the artist relied on some existing model or templates in sculpture or painting, it has not yet been identified and announced. A moment ago, for example, I conducted a Google search, placing in the search box two titles — “The Captive” and “The Wreck of the Atlantic” — only to get in return zero results. Why “The Wreck of the Atlantic”? Let me explain the reason to consider that title as a possible precedent for Couse’s work.

* * *

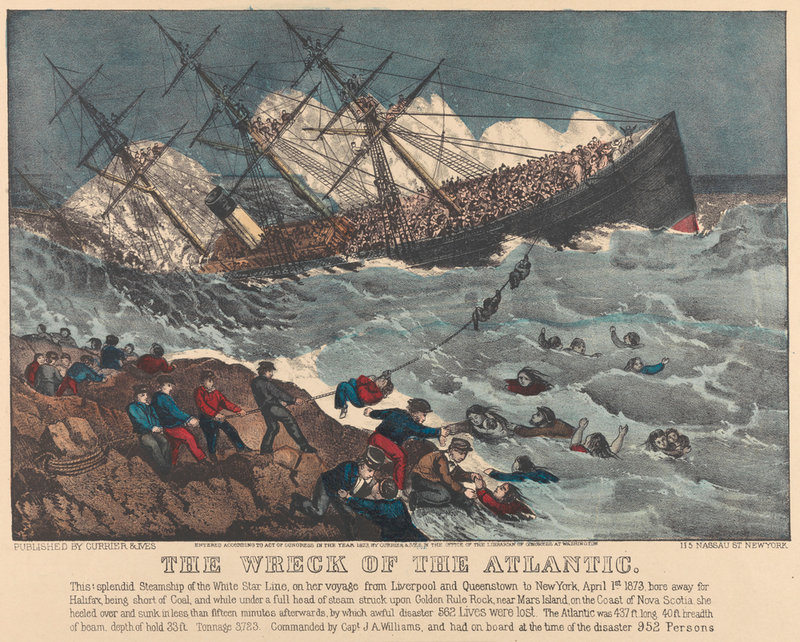

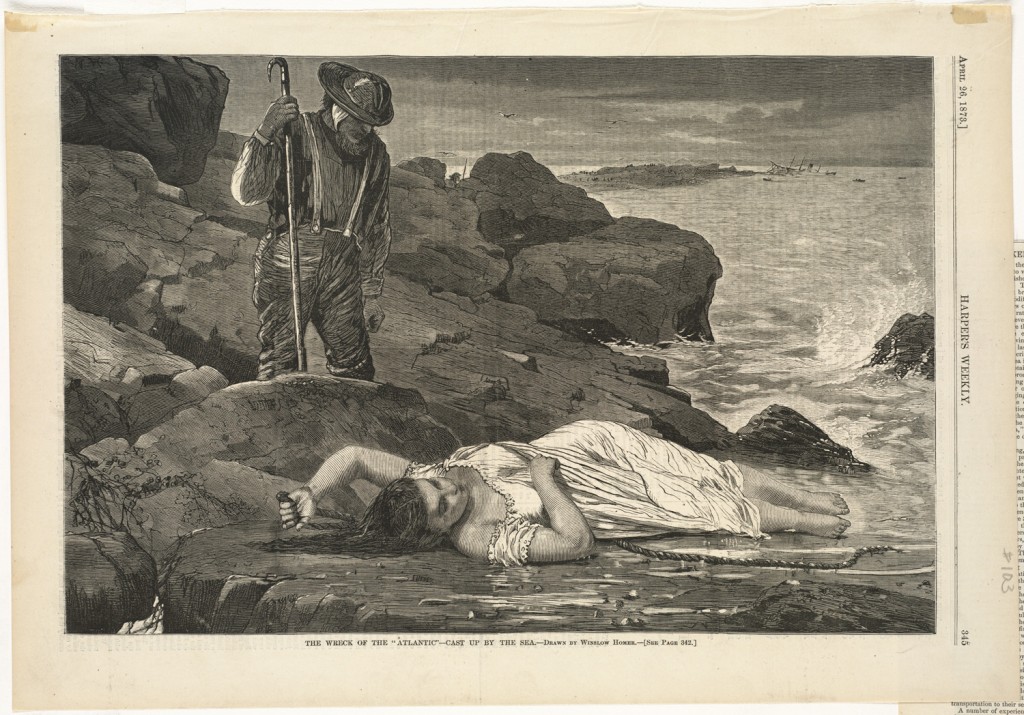

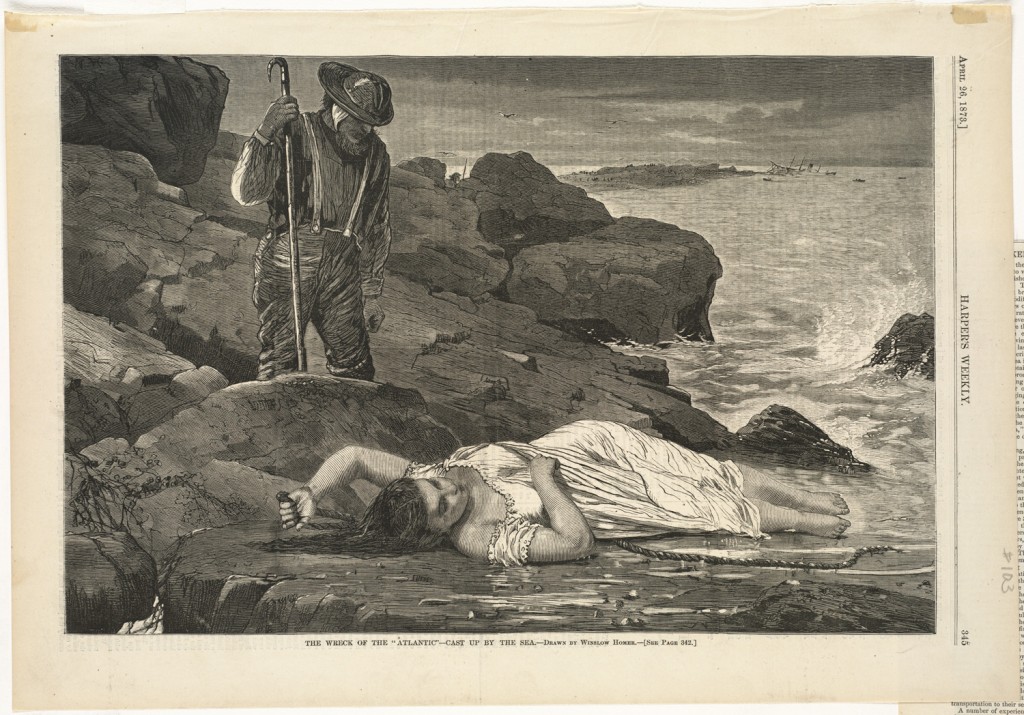

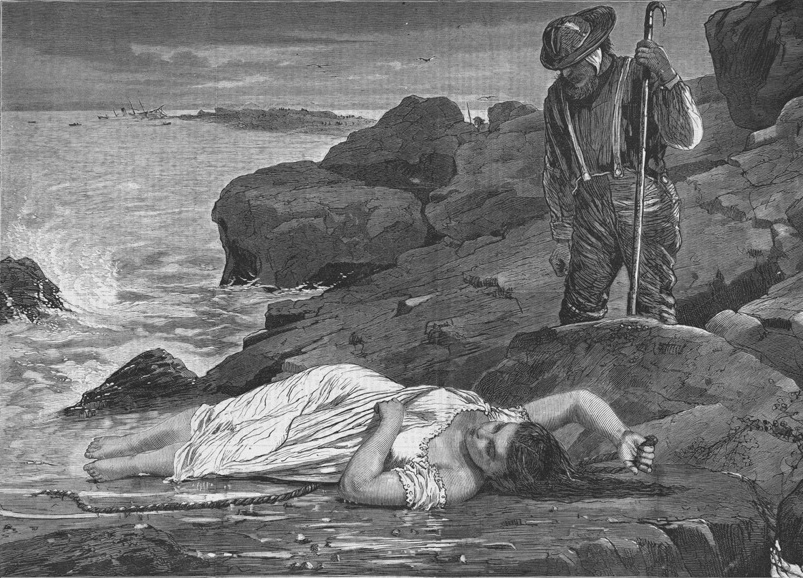

In 1873 Winslow Homer, who was coming to the end of his remarkable period as a commercial illustrator of American lives and events that dated back to the Civil War, submitted to the dominant illustrated journal of the time, Harper’s Weekly, a drawing for a wood engraving that would come to be titled, The Wreck of the Atlantic – Cast Up By the Sea. Published in the April 26, 1873 edition of Harper’s Weekly (Volume XVII, p. 345), the picture was Homer’s response to a devastating shipwreck that had occurred off the coast on Nova Scotia several weeks before, on April 1, 1873.

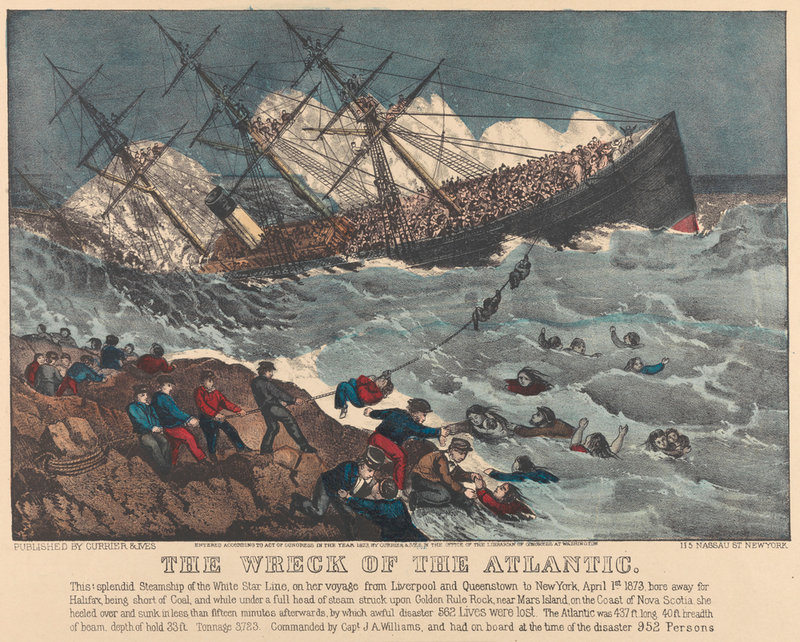

Of 952 passengers and crew onboard the transatlantic ocean liner, RMS Atlantic, at least 535 perished in the pitch-black night, including every woman and child except for one young boy. Historians of the event like to emphasize how this disaster captured popular interest to an extent that was not to be exceeded until four decades later with the sinking of the Titanic. Background and resources about the sinking of the RMS Atlantic can be found here; additional material and links here.

The calamity also caught the attention of the premier American printmaking firm of Currier and Ives, which quickly produced and distributed for public consumption two lithographs, here and here.

.

.

.

Rendered crudely, these broad, journalistic views are crammed with dramatic incidents.

Homer, in composing his picture, chose a different means to convey the tragedy. His design was conditioned in part by the fact that he had not visited the site in person. Instead, as the long-standing “artist-correspondent” for Harper’s Weekly whose artistic skills had recently outstripped his reportorial talents, he chose as his task to imagine the scene and present it to readers in a simpler but no less powerful way. An illustrator transitions to artist.

.

.

It is the day after the terrible night. Homer relegates evidence of the wrecked ship to the distant background in favor of a close-up, immediate discovery: a single victim, a woman found “cast up by the sea” (Note: the image above comes from the Boston Public Library; click on the image for an enlargement of the remarkable details possible from the medium of wood engraving.)

Homer forgoes the busy mechanics of the Currier and Ives depictions. Simply, he heightens the life-and-death drama by establishing a relationship between two figures: a drowned woman and a lone man presumably belonging to the search party called up from a nearby fishing village, dispersed along the rocky shore.

Recent commentators mention the sexual undercurrent of Homer’s treatment. An unnamed annotator of the Brooklyn Museum‘s impression of the print describes the image as “at once pathetic and erotic.” When the work appeared in “100 Days of Homer,” a recent exhibition posted on the tumblr page of the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, the text observed: “In The Wreck of the Atlantic – Cast up by the Sea, Winslow Homer combines real-life events with melodrama.”

Homer’s imaginative visualization of an actual event of a shipwreck, his subjective after-image of the calamity, is at least a conceptual precedent for the course Couse chose to follow when representing an actual event (the Oregon Indian raise) and summarizing its essential meaning. Of interest to me is Couse’s replication of Homer’s formal solution to the task at hand. In both cases, picture-making starts with the relationship of two figures, as that relationship will carry the meaning.

To make more apparent the affinities between the two works, it’s helpful to reverse the direction of Homer’s illustration. This reversal restores the orientation of Homer’s original drawing as transcribed onto the wood engraving block. Useful as well is replacing the colors of Couse’s painting with gray-scale values.

.

.

.

The points of congruence in the two compositions, and the parallels in related details, are many. There is an exact repetition of the relative positions the protagonists. The central energy and tension of both works — the vector of the male gaze — points at the same angle to the identically immobilized female. The supine bodies of the women trace identical forms. There are the echoed details of the drape of their chaste white garments; bare feet; left arms positioned in an unconsciously protective gesture; heads tilted demurely away from the gaze of the man and toward the viewer’s gaze; and the flowing spill of long hair. In both compositions rope is used as a poignant artifact — signifying captivity in one instance and the dashed hope of salvation in the other.

In The Wreck of the Atlantic the male rescuer, though overseeing and closely scrutinizing the female victim, is kept at a discrete remove from her body by the physical intervention of a boulder. Consequently, we read his presence as grounded and still. In The Captive the pose given to the Chief also conveys present stillness. This is achieved by grounding him in a cross-legged sitting posture. These similar pictorial strategies serve a common purpose in controlling the viewer’s reaction. Where Homer implies the present “discretion” and sympathy of the male by hiding from our view the man’s eyes, Couse similarly tempers what Truettner assumes are the viewer’s fears related to complications of gender, sexuality and race by hiding the Chief’s hands in the bondage of his blanket cloak.

And so the question arises: Was Couse aware of Homer’s The Wreck of the Atlantic as he went about planning his first mature figurative work, some 18 years after the senior artist had confronted a similar pictorial challenge?

It’s a tantalizing possibility. But I have to concede it presupposes some lucky circumstance by which a copy of the 1873 Harper’s Weekly wood engraving survived and was available to Couse.

Now, it is a fact that many copies of Homer’s engraving were made and widely distributed. At its peak, the circulation of Harper’s Weekly reached 300,000, and it was also one of the journals that some libraries in the country made it a point to preserve. While Harper’s Weekly’s commanding subtitle — “A Journal of Civilization”! — is forgivable puffery, the publication was well respected and considered to be as a good record of current events as any. Many individual subscribers and readers kept (or one might say, hoarded) back copies as well, just as people in later eras saved their copies of Life magazine, National Geographic and Playboy. Homer’s magazine illustrations in particular were appreciated by discerning eyes. So it is at least possible that Couse, in want of guidance two decades later, could have had access to the image and used it as an aid when creating The Captive.

Note, however, one factor that would strengthen the case for direct influence is not present in this case. I’m not aware of any secondary iterations of Homer’s “The Wreck of the Atlantic” — no reproductions of the picture in other media that would have increased the image’s circulation and survivability. For example, we know that Homer recycled some of his wood engravings of the 1860’s and 1870’s, using them as the source for oil paintings. Examples include Waiting for a Bite, and Dad’s Coming. He presented A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty to the public twice, first as a painting (his own first oil painting) and then as a published wood engraving. However, I’m not aware of him replicating his picture of the shipwreck. Art historians point out that Homer’s The Wreck of the Atlantic provided a springboard to his painting of 1884, The Life Line — but that powerful work, which enjoyed significant national exposure, is a completely different composition.

* * *

There is, of course, another possible explanation for the affinity between The Wreck of the Atlantic and The Captive. Perhaps the central figure of an unconscious female captive in Couse’s composition was derived independently from the same source that Homer used for the central figure in his quite separate drama. unconscious female captive. As for the question of whether Couse then turned to Homer’s wood engraving for guidance when carefully positioning the secondary figure of the overseeing male, we may simply never know the answer.

The likelihood of Couse’s direct access to a model for his primary figure has support in the art historical record. According to recent scholarship, Homer himself probably relied on an existing source — a contemporaneous French painting — when drawing his drowned woman, and Couse would have had equal access to the same source. See Roger Stein, “Picture and Text: The Literary World of Winslow Homer,” in Winslow Homer: A Symposium, ed. Nicolai Cikovsky Jr., Studies in the History of Art, no. 26 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1990), pp. 49-50; and Kathleen A. Foster, “Winslow Homer’s Life Line: A Narrative of Gender and Modernity,” available online, here (the essay is based on Foster’s book-length study, Shipwreck! Winslow Homer and “The Life Line” [Philadelphia Museum of Art and Yale University Press, 2012], which contains an analysis of the reception of Homer’s remarkable nautical rescue painting, as well as additional commentary and bibliography on its sources).

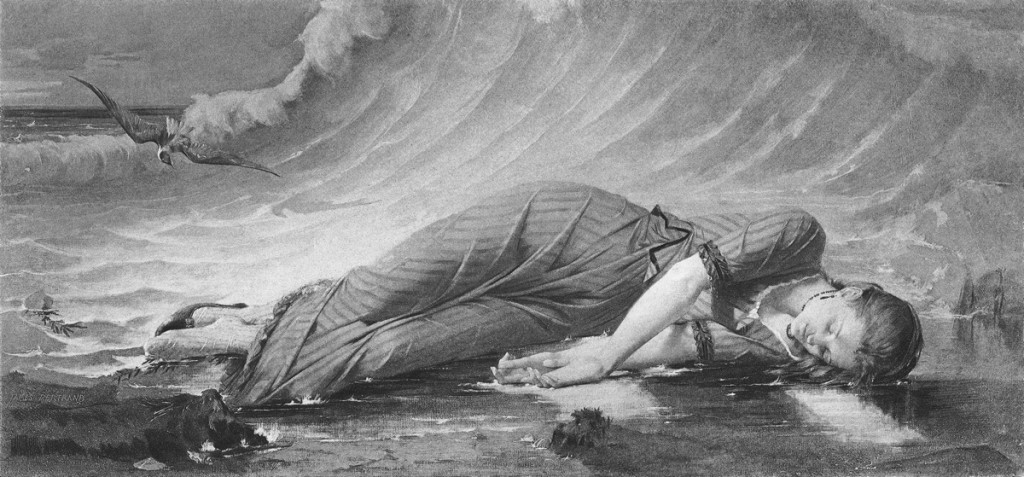

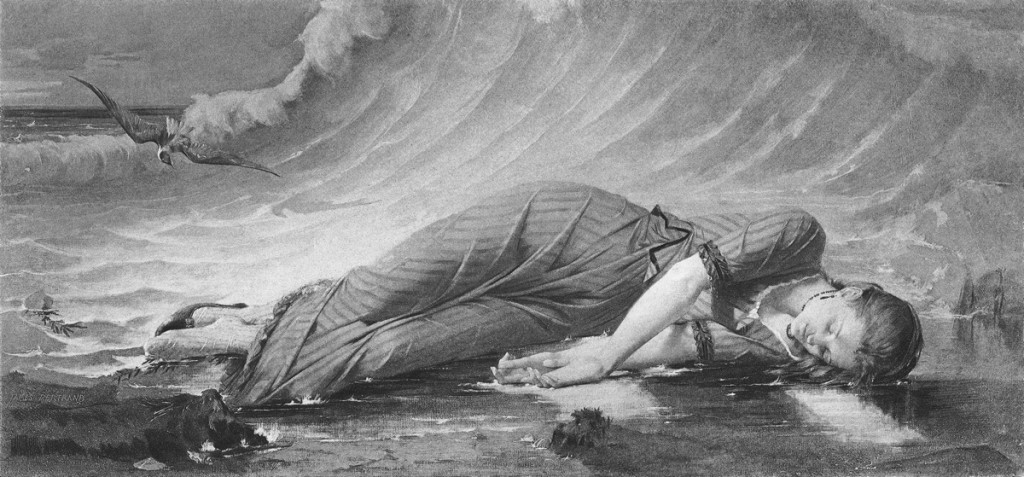

According to Stein and Foster, the painting Homer may have been inspired by is The Death of Virginia (La Mort de Virginie) by James (Jean Baptiste) Bertrand (1823-1887), 1869, oil on canvas, 32 5/8 by 72 1/2 inches.

Unlike Homer and Couse’s narratives, both of which are rooted in historical incidents, Bertrand’s painting is based on a fiction:

“Virginia [was] one of the ill-fated sweethearts described in the 1787 French romantic novel by Bernardin de St Pierre, Paul et Virginie. The novel, which was translated and widely read in Victorian England, centers around a shipwreck, during which the heroine must shed her clothes to be rescued. She refuses to sacrifice her modesty and drowns.”

Now found in the collection of Musée Bertrand, Châteauroux, France, the painting appears to be currently in storage:

.

.

Yet, during the latter half of the 19th century, the image of The Death of Virginia was a popular one and was widely reproduced. Faithful copies (and some not-so-faithful) were made as reduced-size souvenirs for the tourist trade or for export. Below are two examples that appeared recently at American auctions. The first an oil on canvas and the second a painting on porcelain.

.

.

.

How closely Homer followed the placement and contours of the figure of Virginia when he composed his own “Cast Up by the Sea” can best be seen by comparing the two pictures as graphic works. This can be accomplished by pairing Homer’s wood engraving with a version of Bertrand’s oil painting translated into a graphic medium. One such translation was made by the international art dealer Goupil & Cie, based in Paris and with shops in New York City and other locations. In 1888 the firm began selling a gravure reproduction of “Le Mort de Virginie.” Here it is, followed by Homer’s work (once again I’ve reversed the direction of the published wood engraving to simulate Homer’s original drawing of the scene):

.

.

.

Bertrand’s picture, then, was almost surely part of Homer and Couse’s visual memory. In fact, the appeal and influence Bertrand’s painting on American artists was brought to my attention yet again when I recently came across the following image of a small painting by Kenyon C. Cox (1856-1919) that will be auctioned on October 24, 2013 at Shannon’s Fine Art Auctioneers: Reclining Nude on a Beach, oil on panel, 10 x 12″, signed on the reverse. This undated study looks to me to be an offspring of the same ancestor:

.

.

Update 03/13/2016:

Another copy of Bertrand’s The Death of Virginia has surfaced recently at auction. The painting, whose dimensions (33″ x 73″) are virtually the same as the original oil on canvas, is boldly signed by the artist and dated 1875. That date, just six years after Bertrand completed the original work, suggests an expanding interest in the image. Photos from Myers Fine Art Auctions, St. Petersburg, FL:

.

.

.

.