.

Over a decade ago the distinguished critic Jonathan Yardley, whose book reviews appear in the Washington Post, observed, “There is no such thing as a powerful book critic.”

That remains true today.

Though there is reason to lament this state of affairs, it is not the diminished cultural impact of book reviewers that worries me. Rather, what concerns me is an overall decline in the quality of book criticism appearing in mainstream media publications. There is still a sizable number of people who read book reviews, and we deserve better.

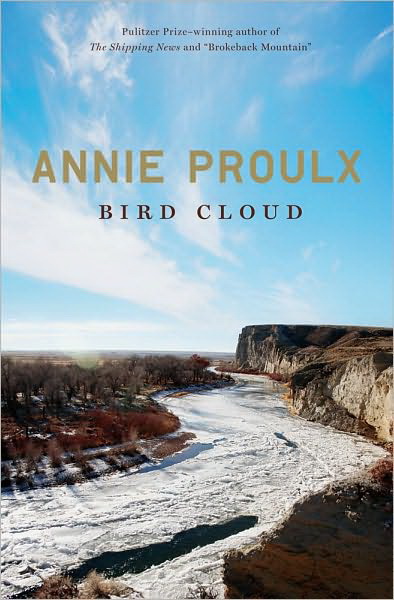

I’ve been monitoring newspaper and magazine critics’ reactions to “Bird Cloud,” Annie Proulx’s non-fiction book released earlier this week. I’m finding that a diseased strain of “reviewing” — a strain that first came to my attention last year around the time of the publication of Jonathan Franzen’s novel, “Freedom” — appears to be spreading.

I’m speaking of a mode of critical attack that exposes not so much the flaws of the book under review as the deficiencies of the book reviewer who indulges in its practice. This baleful approach is characterized by ad hominem attacks delivered in a voice that blends self-absorbed gusto with made-up grievance.

If this virus has a ground zero it might be an execrable “Freedom” review/profile from the pen of Jennie Yabroff, an article that Newsweek editors unwisely chose to publish last August as another marker in the decline and fall of that once vital periodical.

A month later the self-absorbed component of the style was placed center-stage in a review of Philip Roth’s latest novel, “Nemesis,” in The New York Times. In the piece, Leah Hager Cohen spends the first five paragraphs, a sizable chunk of the entire piece, talking about herself, her history, her touch points with Roth’s oeuvre, her moods, her equivocations, her journey. Yes, it’s all about me-me-me, before I go head-to-head with the author. This diversion into the self is “relevant,” she says. To her credit, she then goes on to say intelligent things about the book, judging it fairly on its merits.

Most of us who’ve reached middle age can sense when someone else has pre-judged a matter. I am especially concerned about reviews that signal the presence of prejudice.

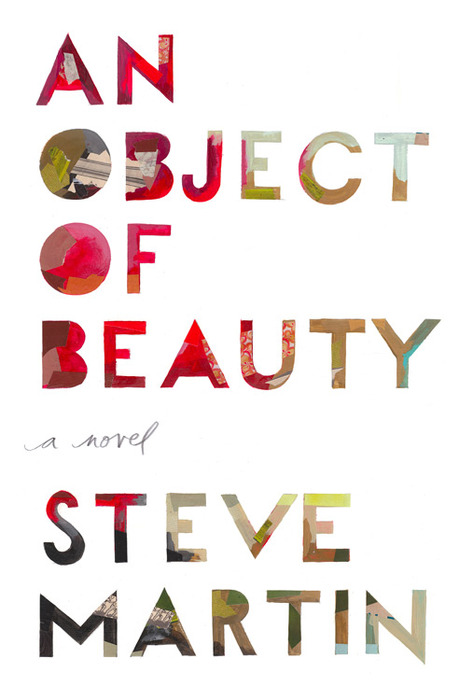

One such stink bomb, a book review that adds to the mix an aggrieved whine and some tired preppy insults, landed in December. In an online review posted by The New Republic, Andrew Butterfield does a hatchet job on Steve (“lazy”) Martin’s novel, “An Object of Beauty.” Typical of Mr. Butterfield’s approach is the bloodless delivery of this calumny: “All [Martin] makes you feel is that your ignorance should arouse your envy—that you, poor thing, are less fortunate than he and the fancy people in his book.”

Now, personal rants of this sort, especially those that rise to histrionic pitch, are usually full of howlers, and Butterfield does not disappoint. For example, his command of the book is so slipshod that he is unable ever to get the book title correct, not even once. Three times he refers to it as “The Object of Beauty.” (But wait, you say — is it possible a gremlin slipped Butterfield a rogue, evil version of the good book I had the pleasure to read?) His paragraph assuring us there has never been an art collector who ever wore an Armani suit is a real hoot.

The decline continues to manifest itself in 2011.

Early in his review of “Bird Cloud” published in the New York Times this week, Dwight Garner lays down a marker, dubbing the book “shelter porn.” It can be viewed, he says, as a product of “a wealthy and imperious writer who . . . believes people will sympathize with her about the bummers involved in getting her Japanese soaking tub, tatami-mat exercise area, Mexican talavera sink and Brazilian floor tiles installed just so.” In truth, the tub installation problem that needed correcting (described on page 118) involved a clogged outflow drain which caused water to leak to the downstairs library, threatening Proulx’s research files and vital book collection. I wonder how Garner would react if his auto mechanic were to chide him for selfishly wanting his oil-leaking car engine tweaked “just so.” Oh, never mind.

Then there are the words “tatami mats.” These four syllables have an exotic sound that attracts easy mockery, but does Garner really want to throw his lot in with the class warriors who made hay of Obama’s expression of arugula-love, back in 2008? And what’s with Garner’s prissy “just so” fillip, anyhow? I defy any reader to come away from “Bird Cloud” with the impression of Annie Proulx as a prissy lady (although I have to admit that taunt — Prissy Annie Proulx! Prissy Annie Proulx! — feels kinda good tripping off the tongue). I also defy anyone to come away from “Bird Cloud” with the feeling that Proulx wants us to “sympathize with her” for any of her travails, large or small.

While others (in Slate and in The New Yorker, before which I normally bow down in awe) are saying sweet things about how clever Garner’s review of “Bird Cloud” is (I agree Garner can be witty, and he delivers verdicts with a good comic’s sense of timing), I have a sneaking suspicion neither of the encomium-givers (Timothy Noah and Ian Crouch) has read “Bird Cloud” in full.

One thing I know for sure: no one’s interested in my reviewing their reviews of a review of a book. To get caught up in the vagaries of a posse of literary critics — a dysfunctional family if ever there was one — is not conducive to anyone’s mental or moral health. So, returning to the merits of Proulx’s “Bird Cloud,” I simply will say as a reader I disagree with Garner. With him you get a twofer: a misunderstanding of the book and a misreading of the author.

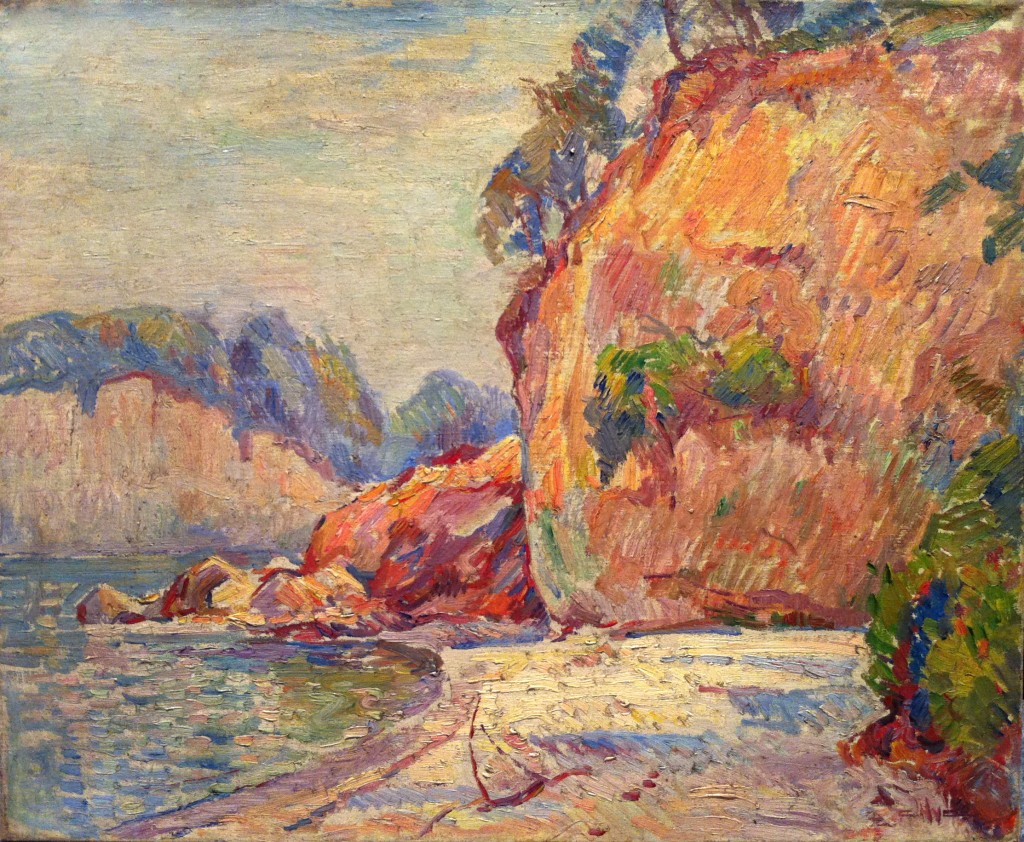

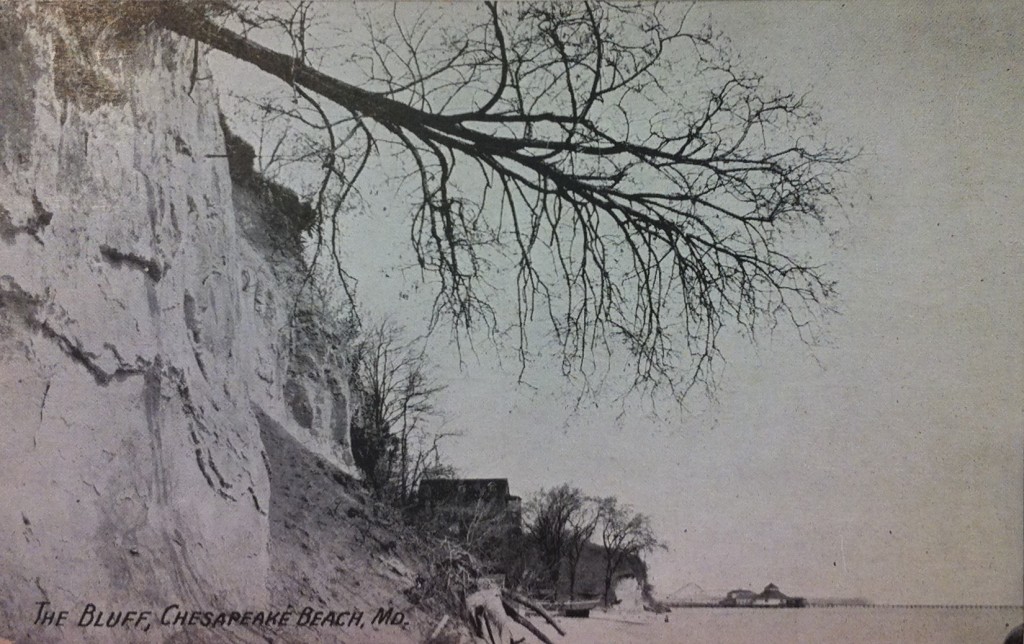

There has always been a moral component to the best literary criticism. That tradition, when examining “Bird Cloud,” would call on the critic to examine the environmental ethic so important to Proulx’s experience on her 640 acres of raw Wyoming rangeland. Keep in mind this is land the author decided to purchase by trading in her fair-gotten gains from her writings. The seller was The Nature Conservancy, and it is under the constraints of rigorous covenants that Proulx enjoys the property.

Few if any reviewers appear interested in this aspect of the book. Instead, critics stir up (or, in my opinion, make up) grievances. Garner, for example, finds it “deplorable” that Proulx writes so freely about “the perks of [her] success.” Joining Garner in his descent into status resentment is Michael Upchurch, who, in his review of the book in the Seattle Times, gives Proulx the raspberry for overreaching. He sums up his disdain for the 75-year-old author with this barb: “You wonder if Proulx has a single ounce of common sense.”

A notable element in these complaints is the loopy premise that the status of America’s economic health at the moment of a book’s publication could justify placing cautions, if not actual fetters, on free expression. Can that really be what these scolds advocate? Consider how Upchurch upbraids Proulx: “Her decision to publish this account of her extravagance when so many Americans are losing their homes seems in dubious taste.”

All too often nowadays the cultural impotence of book critics’ messages is matched by the imbecility of their content.

I wonder if it’s time to spin a variation on the Catskills resort joke (the food is terrible . . . and such small portions!).

How about this: What book critics write is terrible . . . and it has no impact!

.