.

.

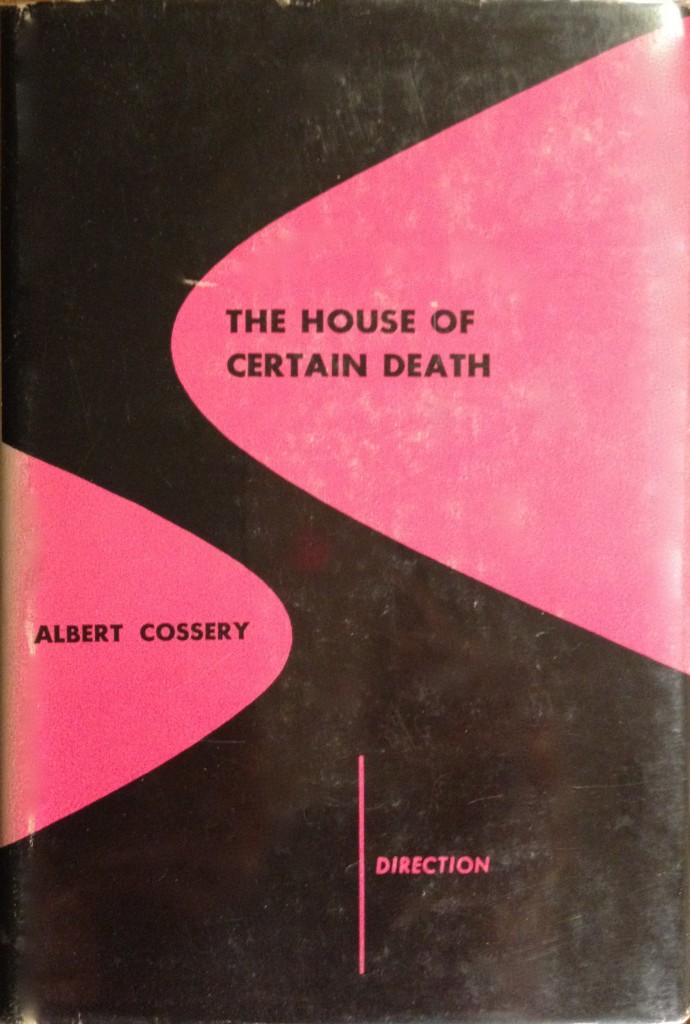

THE HOUSE OF CERTAIN DEATH (La Maison de la Mort Certaine, 1944) is Albert Cossery’s first novel. It marks an apprentice writer’s transition from his first book, the collection of short stories titled “Men God Forgot” (1940), to the accomplished later novels for which he is best known.

The author introduces us to a group of Cairo inhabitants, a handful of impoverished families living in a rundown tenement located in the squalid Native Quarter. We get to meet them during a cold winter season that becomes “a course of unlucky days.”

They include Chehata, an out-of-work carpenter who has gone mad due to his inability to provide food for his wife and daughter; Rachwan Kassem, an oil stove repairman who succumbs to anger; Soliman El Abit, a melon peddler who succumbs to fear; Souka, a café singer in unrequited love with an abused married woman; Abd Rabbo, a street sweeper who selfishly abandons the neighborhood; Bayoumi, a monkey trainer who provides limited comic relief; Kawa, a man resigned to painful old age; and Ahmed Safa, a hashish addict who, alone among the band, can read and write.

The character most interesting to the modern reader, especially one who has followed the impact of the 2011 Arab Spring, is Abdel Al, an unemployed carter. It is he who, in the final third of the book, undergoes a personal awakening — a new political consciousness — that guides him, tentatively, to thoughts of revolt.

As for a plot, the book is meager. We witness a few unsuccessful attempts by the tenants to confront their landlord, Si Khalil, and force him to do something about a building in imminent threat of collapse. The notion of a house in ruins is an idea Cossery again would examine 55 years later in his final novel, “The Colors of Infamy” (1999), whose plot turns on a catastrophe caused by a slum landlord’s indifference.

In this earlier story the crumbling tenement takes on a heavy — and some will say heavy-handed — symbolic weight as a sign of the corruption of Egypt’s social and political. We are reminded often that the crack in the tenement’s foundation is growing (“day by day its dimensions were becoming more alarming”). As we learn more and more of the personalities and perilous individual status of these forgotten men, women and children, we also learn of their collective peril. Cossery repeatedly inserts in the mouth of one character after another the exclamation, “Don’t you know that the house is about to crash?”

Throughout his career Cossery was prone to florid writing, a dubious skill he eventually learned to apply selectively. Here in his first novel this tendency is wholly unchecked. For example, the carter’s eight-year-old son, wandering the neighborhood streets, is described as being “alone in the immense charnel house where men were murdered by torment and tyranny.” As well, there is a great amount of repetitive and tiresome text separating rare moments of prose that chill us with savage revelations.

As in better works by this author, an oppressive atmosphere prevails. Its cause is an unresolved tension between apathy (“The world could crumble, the world could rot; the tenants would not move”) and action (“the soul-stirring force of revolt”). The problem I had is Cossery’s avoidance of building a case either way. Readers will wonder, Where does the author stand?

One would imagine he stands with Abdel Al who comes to realize how man has “concealed within him, secrets that could shake the world.” Abdel seeks to be sustained “by something bigger than himself.” The education of Abdel Al (“there are certain things that I am just beginning to understand”) is finely evoked.

“Ever since I began to think about the misery in which we all live, I can feel ideas sprouting inside me like poisonous weeds. I am always trying to sort them out, but just when I’m about to grasp them, they suddenly retreat into the shadows. And I am never able to catch up with them . . . . He was filled with a feeling of impotence that tortured him like an open sore.”

“He realized that, by himself, he could do nothing. What could one man accomplish? A lone man was a powerless thing, fit only for sorrow and for tears. Abdel Al would have liked to see everyone aroused by the same feeling; he hoped for a universal awakening for those who were affected by a common misery and a mutual desire to live.”

How disappointing it is for the reader that his evolution of thought, so harrowingly relayed by Cossery, leads . . . nowhere.

The book concludes with a climactic confrontation between Abdel Al and the landlord Si Khalil in an unnamed public square (could it be Tahrir Square?). It peters out with a mere exchange of insults and slogans. The tenant warns of an eventual “vengence of an oppressed people that nothing can stop”; the landlord responds: “You’ll be dead long before that.”

It is as if Cossery lost the nerve to pursue this grand theme.

“The House of Certain Death” is currently out of print. The likelihood of its revival in today’s uncertain publishing world is slim. Ardent and adamant Cossery readers will want to track down a used copy, if for no other reason that to trace the early development of this excellent writer. But the literary explorer should be prepared to find an awkward book, one lacking the controlled pace, the sly humor, and the intelligent talk that enlivens prime Cossery.

For those treats, check out the newly translated editions of the author’s “Proud Beggars” and “The Jokers,” both published by New York Review Classics.

Note: My reading was of the 1949 hardback edition of “The House of Certain Death” translated by Stuart B. Kaiser, published by New Directions as book 11 in its Directions Series. If ND decides to re-issue the books, news of that will likely be posted here.

.