.

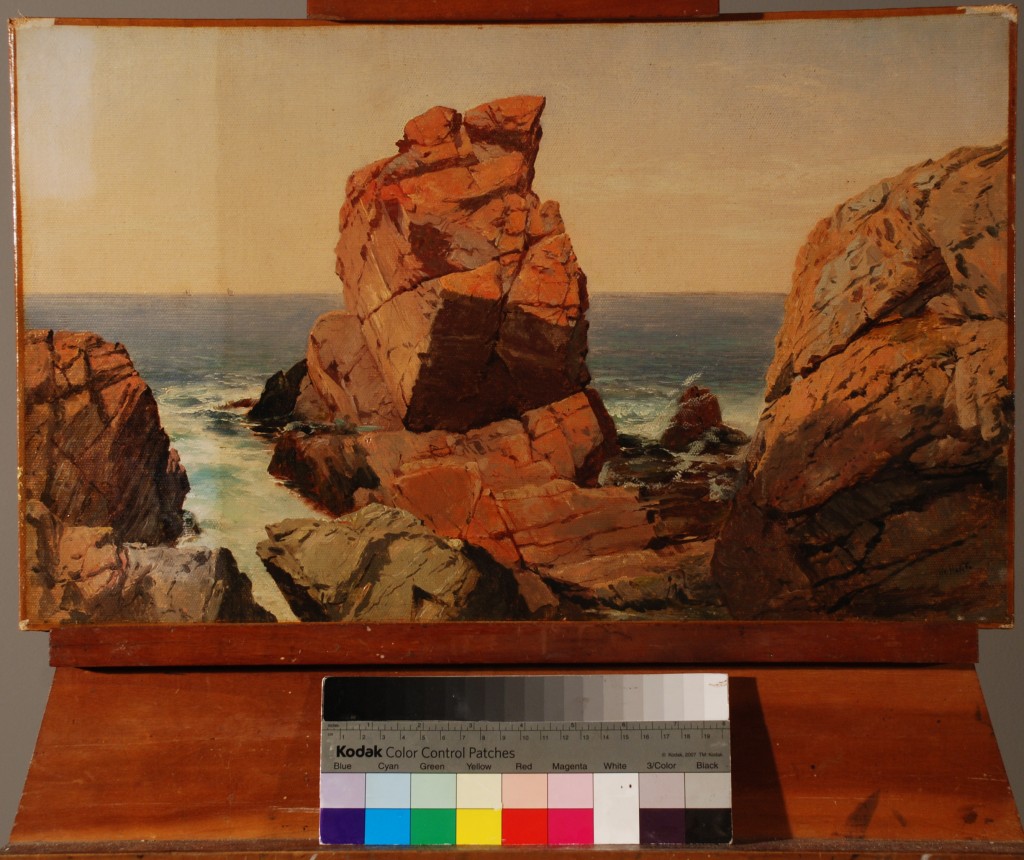

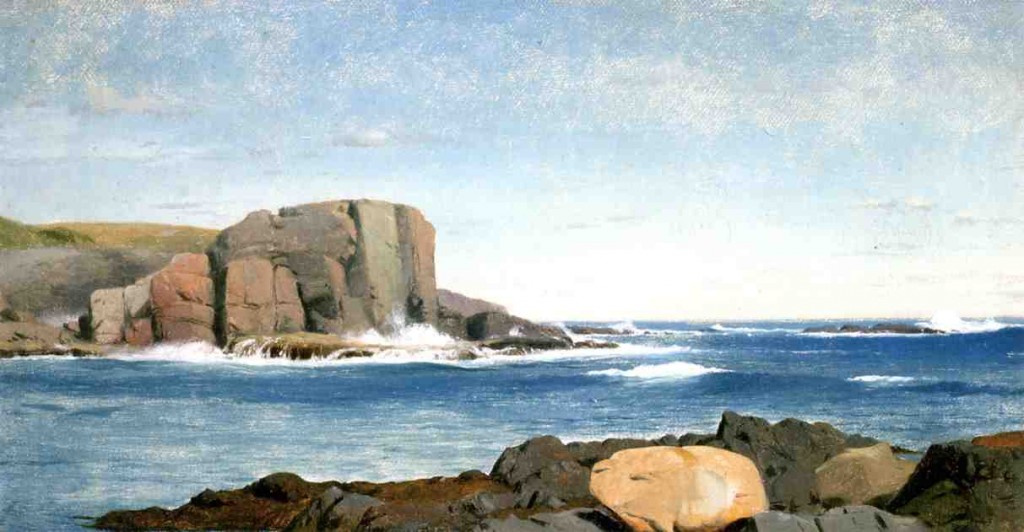

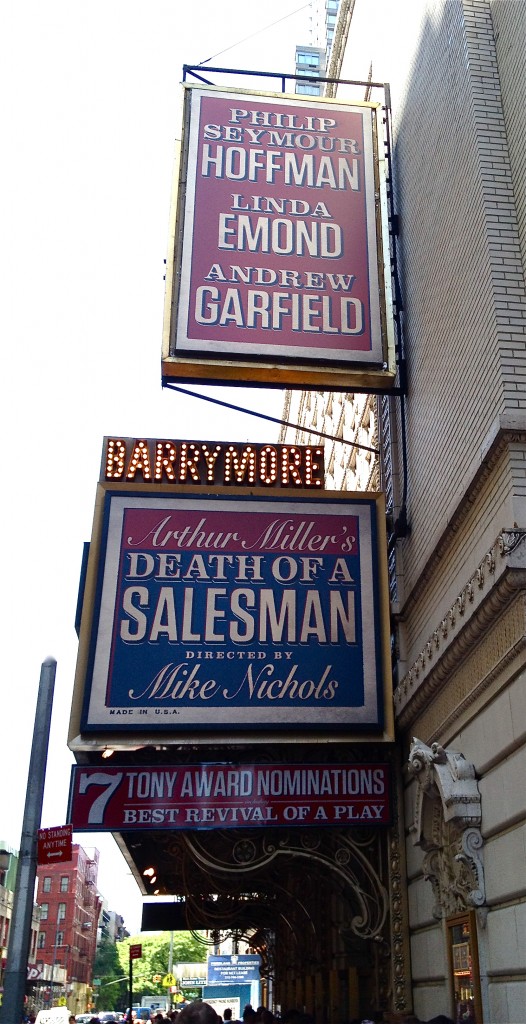

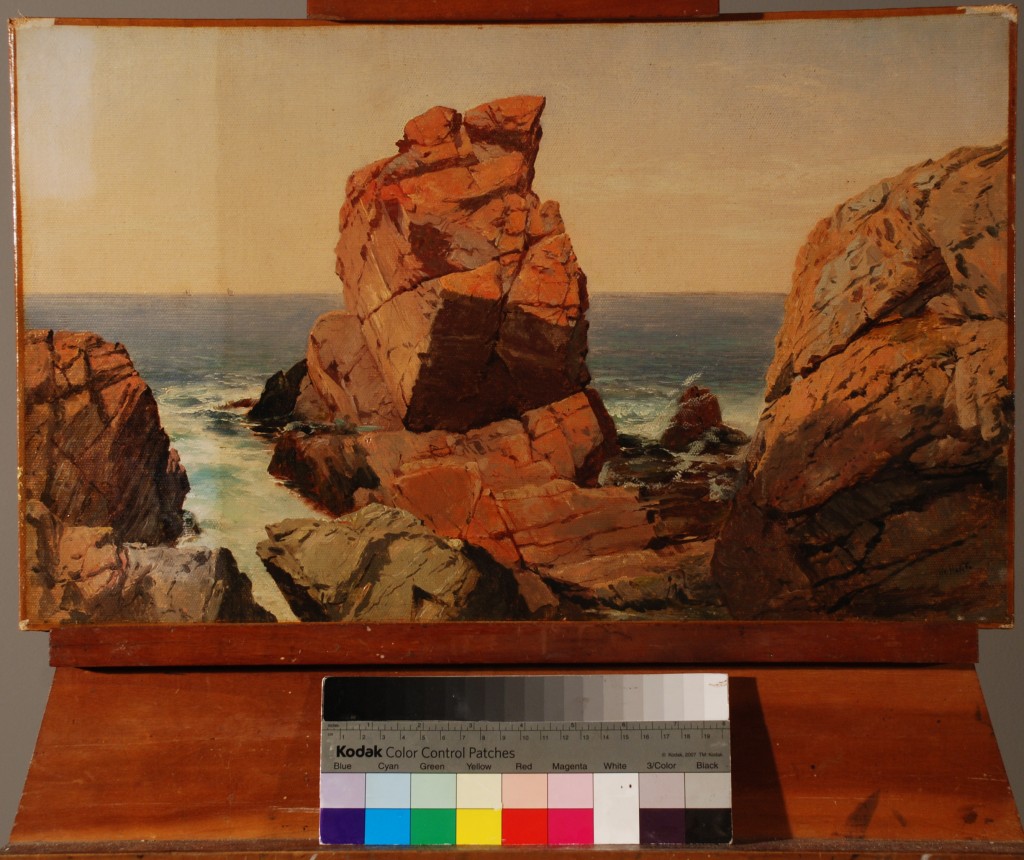

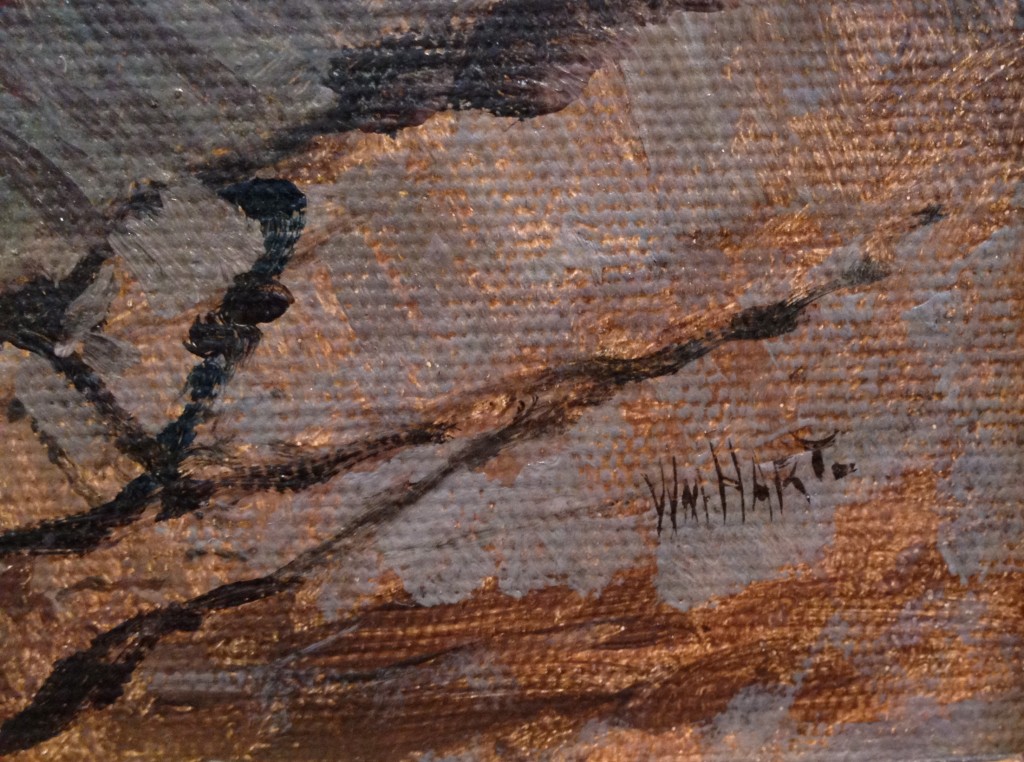

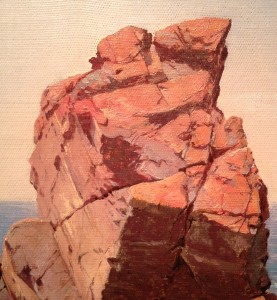

This spring I added a piece to my collection of mid-19th-century oil sketches by American artists. The painting, by William Hart (1823-1894), is an oil on canvas, 12 by 19 1/2 inches, titled “Rocks on the Shore.”

.

.

Sometimes it takes time for a work of art to reveal its hidden beauty, not to mention the circumstances of its creation. This painting is a good example of a slow reveal.

So far I’ve been led to two revelations.

* * *

The first discovery emerged when I decided to uncover the work’s original appearance. A century and a half of accumulated dirt and time-yellowed varnish had obscured its glow. As always I relied on the technical skills of Arthur Page, a veteran painting conservator. His studio removed the grime and old varnish that had veiled the artist’s original accomplishment.

This photo is from an early stage of conservation treatment (note the upper left quadrant).

.

.

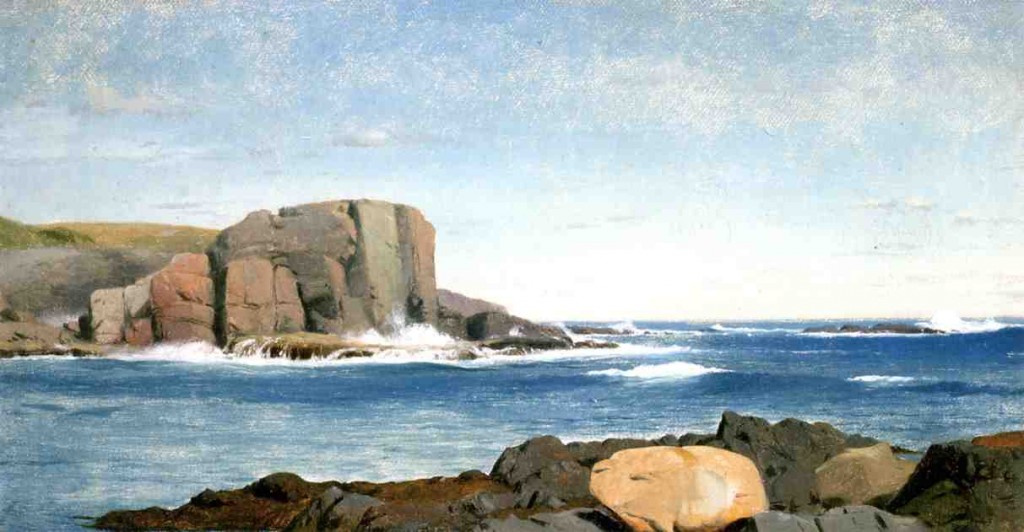

The result of the cleaning was striking. Revealed was a fresh, high-keyed painting of a bright day that attracts the viewer’s eye. The scene Hart depicts has an immediate impact. This is a sign of a fine plein air sketch — a painting completed, or at least begun, in the open air, as the artist engages in a face-to-face encounter with the natural environment, discovered here-and-now.

.

.

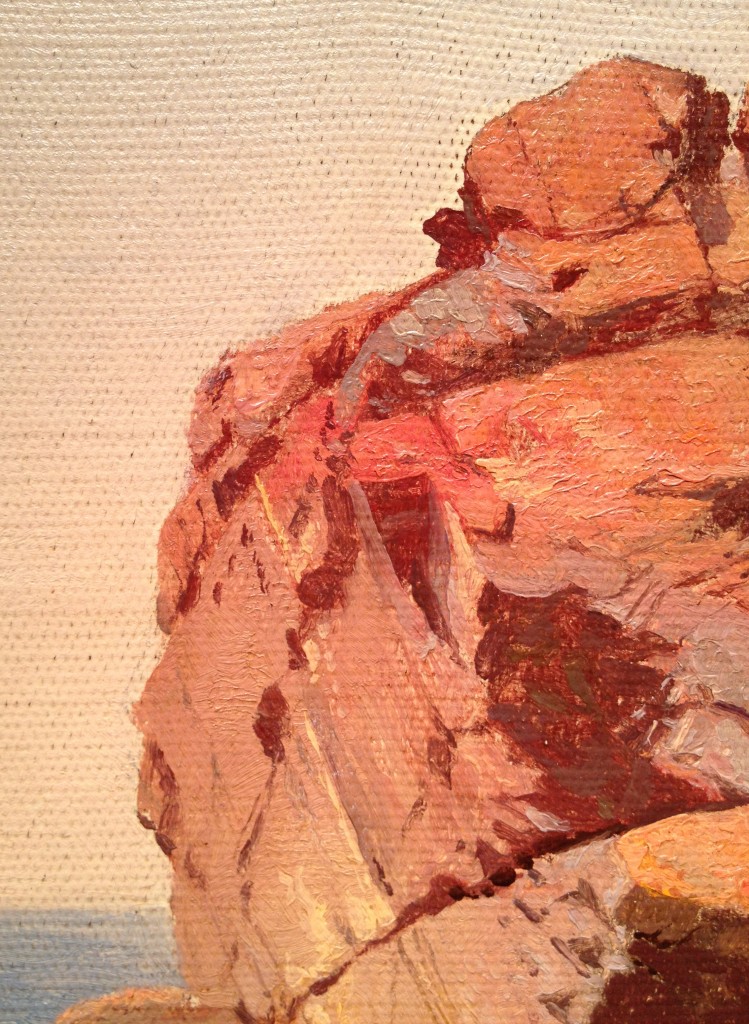

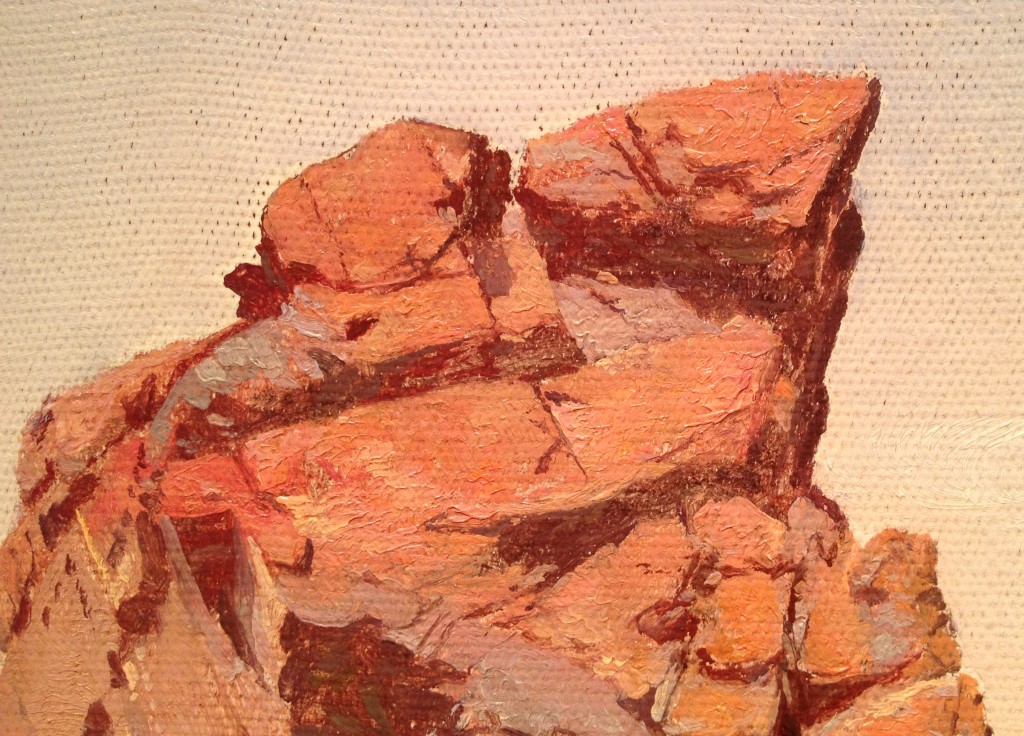

Some of the details that emerged, brightly:

.

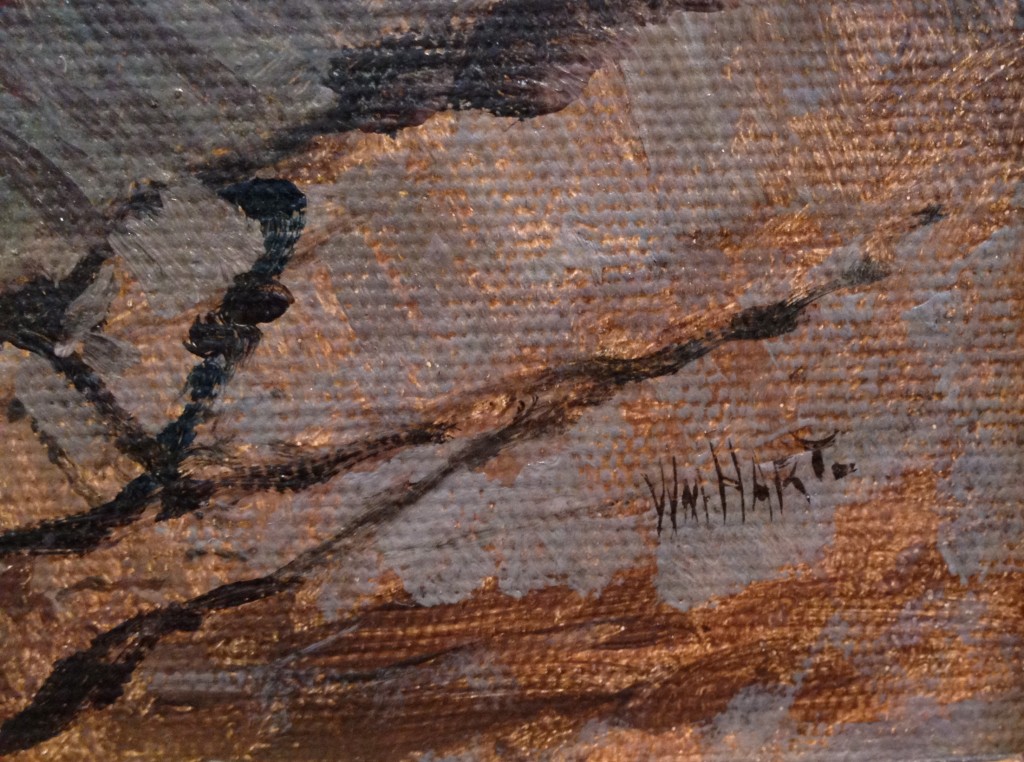

Signature in the lower right corner

.

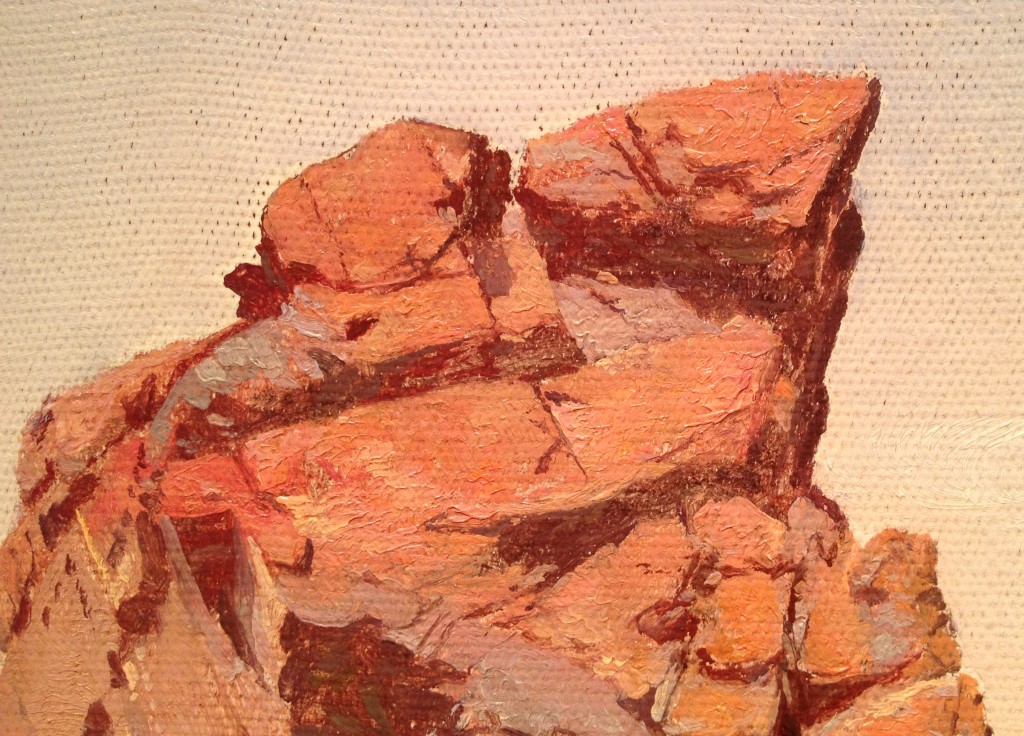

Pencil outlines

.

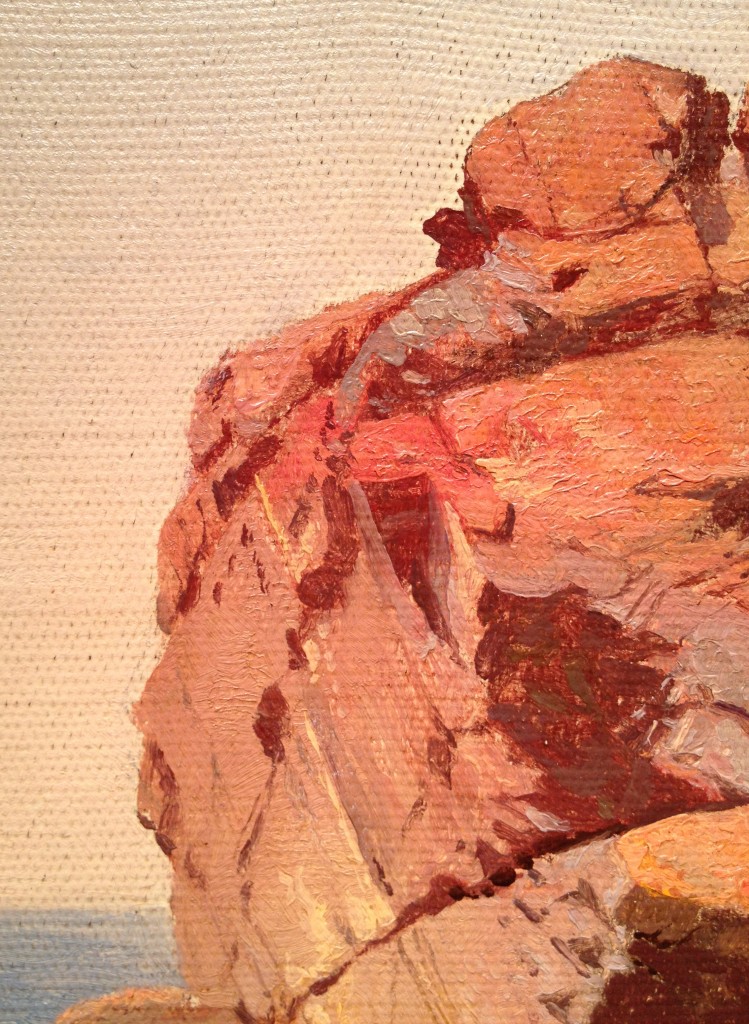

Hart’s facility in handling a colorful, paint-laden brush

.

The artist’s attention to the smallest phenomenon, such as grasses rooted in the boulder’s crevices (click on photo for enlargement)

.

* * *

The second discovery I made was the location Hart chose to capture in paint. As I’ll explain, the path to a final determination of that site was not smooth, because the search was first waylaid by a false identification made by an art historian.

Aside from the artist’s signature, no other inscriptions appear on the canvas, verso or recto, nor on its original stretcher. This meant finding the scene’s location and the date Hart painted it would have to depend on information external to the work itself.

The auction catalog’s description of the piece contained a bit of speculation:

“This fine example of the subject [a rocky shoreline] by Hudson River landscapist William M. Hart [sic: William Hart never used a middle initial; “WM” is how he abbreviated “William”], a Scottish emigre who settled with his family near Albany, New York, […] probably records a spot of coast in Maine, near Grand Manan where he frequently painted.”

I, too, thought Maine was a good guess. But exactly where in Maine? Surely such a dramatically-wrought promontory, whose every cut and curve, plane and shadow, was meticulously traced by Hart’s eye and hand, must be some familiar spot. It must have been known and appreciated by Hart’s fellow itinerant artists who traveled up and down the New England coast in search of scenes of picturesque and sublime content. What other artists were drawn to record this vista? Did their works survive?

Surfing online for answers, I found a few other examples of Hart’s own paintings of sites where rock terrain met the sea.

.

.

.

.

But these paintings were of different formations, and none of the information connected to them pointed to the location of my painting.

Then, a Eureka moment — or so I thought at the time.

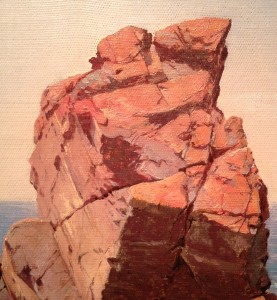

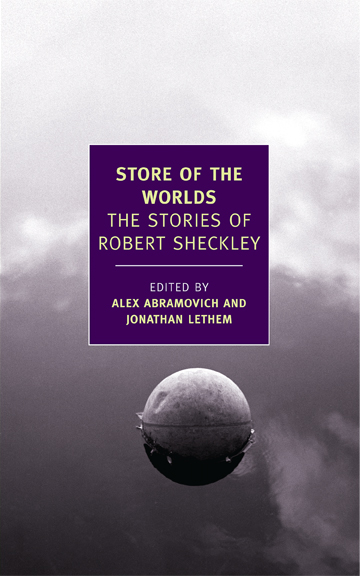

Paging through John Wilmerding’s “The Artist’s Mount Desert: American Painters on the Maine Coast” (1994) (currently out of print), I came to the chapter devoted to William Stanley Haseltine (1835-1900). Haseltine, like Hart, was a member of the second generation of the Hudson River School, America’s first native school of landscape painting. He is best known for his precise renderings of the rocky coast of New England. Starting in the late 1850’s and continuing well into the next decade, Haseltine traveled from Rhode Island’s Point Judith to Maine’s Mount Desert Island, along the way executing drawings and oil sketches that he then used as source material for larger works he would complete in his studio. Bold rock formations were his inspiration.

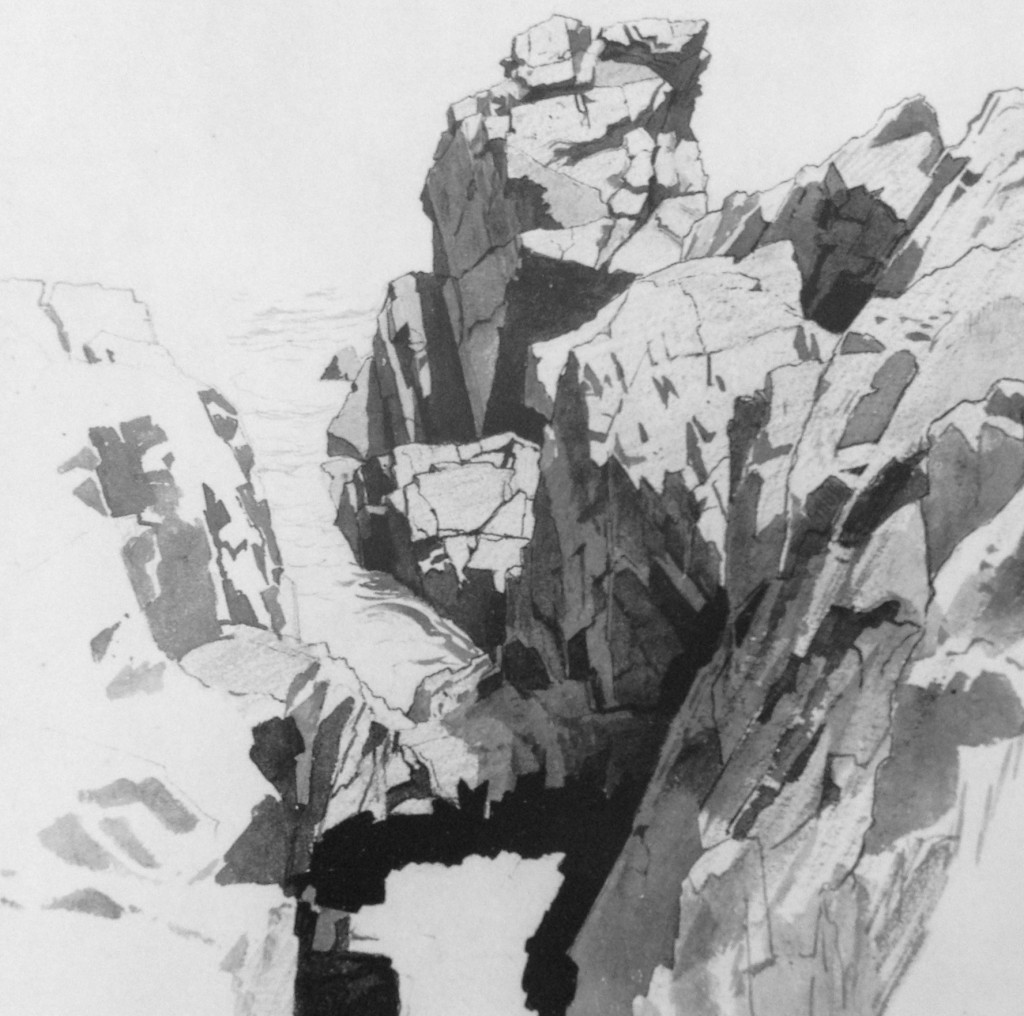

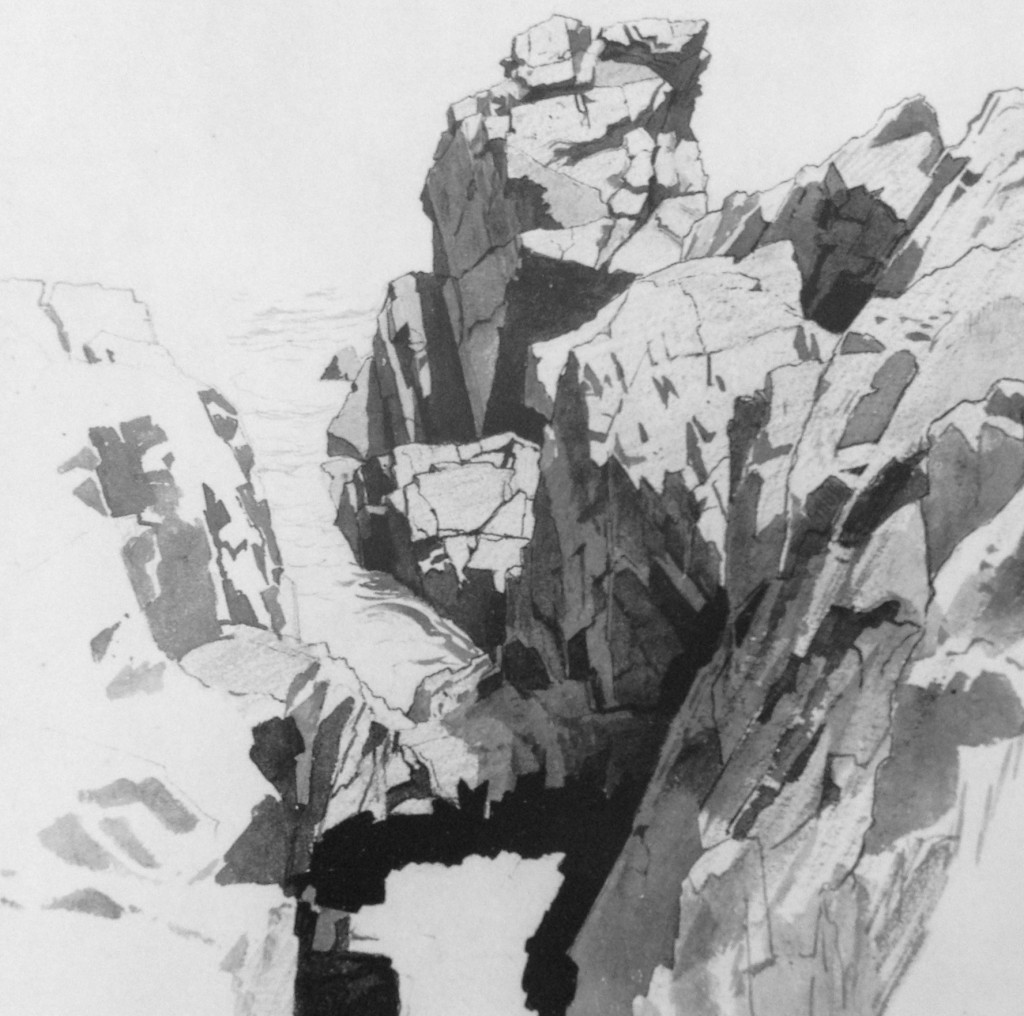

On page 112 of Wilmerding’s book there is an illustration of one of Haseltine’s many beautifully-rendered drawings from 1859. It is titled, “Thunder Hole, Mount Desert Island” (pencil and grey wash on paper, 15 1/8 x 21 9/16 inches, private collection):

.

.

If you examine the central monolith in the drawing and compare it to the William Hart painting you will discover — it is a match!

* * *

When Haseltine recorded this view of a massive rock formation overlooking the sea, it appears he stood further back from the water than where Hart managed to climb. Haseltine also positioned himself a bit to the right. This resulted in slightly less than the entire huge craggy mass at the apex of the composition being visible, when compared to the view recorded by Hart. Regarding that dominating monolith, there’s no mistaking the fact that it revealed the complexity of its facets to Haseltine and Hart in identically clear fashion. I’m hard-pressed to find any significant differences.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Both artists recorded the site at about the same time of day; the sun casts shadows of similar direction and depth. Yet of the two artists, I sense Haseltine, ever the geologist, was the more faithful transcriber of the position and shape of the flanking structures on the left and right. Hart, less a literalist, seems to have taken liberties in portraying the structures to the left and right of the focal point whose beauty most intrigued him. This is also understandable when you consider Haseltine’s aesthetic approach when drawing with pencil and ink wash involved creating an interesting black, grey and white design that floats upon the white expanse of a flat sheet of paper. To the extent Haseltine wanted to reformulate the actual scene in front of him, he could accomplish that without rearranging the physical matter before him, but by modulation of tone — assigning various shades of grey to each stationary element in service to his two dimensional design. Hart proceeded differently. In creating his sketch in oil paints, he enjoyed the added resource of color. While generally respecting the fidelity-to-nature imperative of mid-19th century painting, Hart would allow his composition to stray from the actual. He felt free to rearrange matter at the behest of other, superior values.

In a later chapter in “The Artist’s Mount Desert” (pp. 129-130), Wilmerding grants only passing mention to William Hart (applying to him words of faint praise such as “competent” and “clever in a modest way”), though he does say that records exist showing Hart was painting at Mount Desert from 1857 to 1860.

With these bits of evidence falling into place (and with Wilmerding’s ostensibly reliable scholarship), I was fully prepared to re-title this William Hart painting, “Thunder Hole, Mount Desert” (ca. 1859).

And yet there was something that bothered me — a nagging question arising from a practical observation. It was this:

Why does Thunder Hole look so different today?

* * *

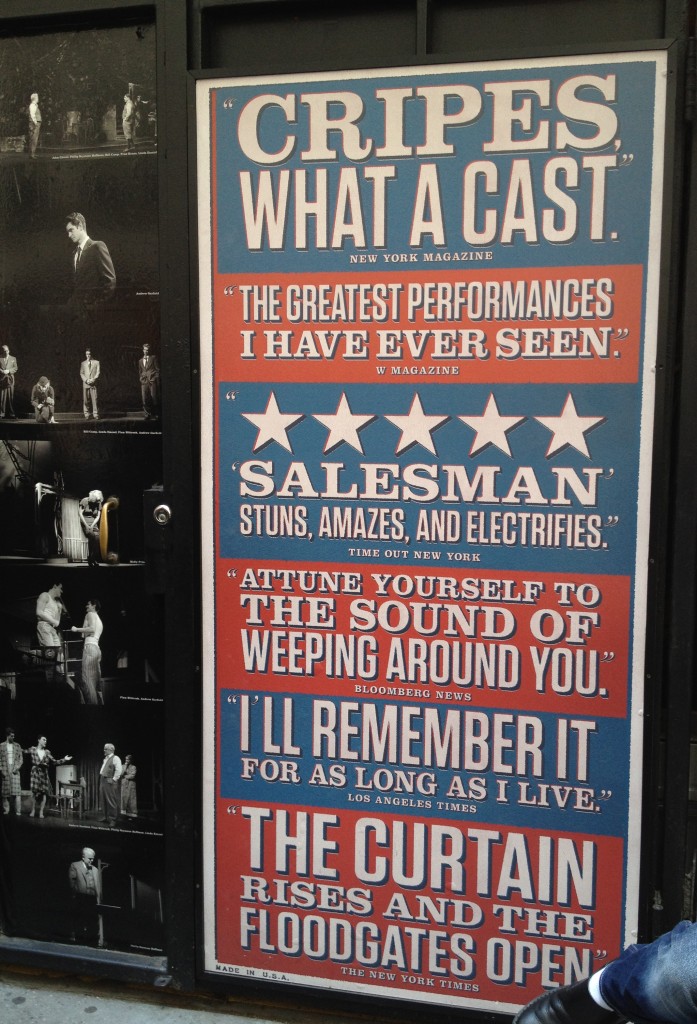

Today, Thunder Hole is a tourist stop for visitors to Acadia National Park on Mount Desert:

Nothing symbolizes the power of Acadia National Park as much as Thunder Hole does. When the right size wave rolls into the naturally formed inlet, a deep thunderous sound emanates. The cause is a small cavern formed low, just beneath the surface of the water. When the wave pulls back just before lunging forward, it dips the water just below the ceiling of the cavern allowing air to enter. When the wave arrives full force, it collides with the air, forcing it out, resulting in a sound like distant thunder. Water may splash into the air as high as 40 feet with a roar!

Videos of the phenomenon are available here and here.

Thunder Hole is on the east side of the Island, south of Sand Beach and just north of Otter Cliff:

.

.

Changes in light and moisture can alter the color of the cliffs from grey to pink, orange, even red:

.

.

.

Dynamics defined the site. But still I wondered, had the erosion of wind and water so altered the structures meticulously depicted by Haseltine and Hart that, today, the distinctive central rock formation has been transformed into . . . this?

.

.

I didn’t think so.

* * *

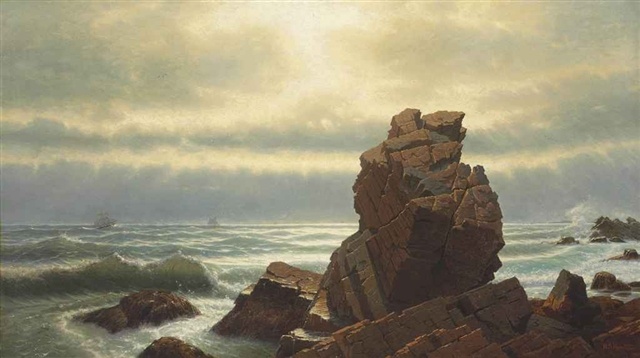

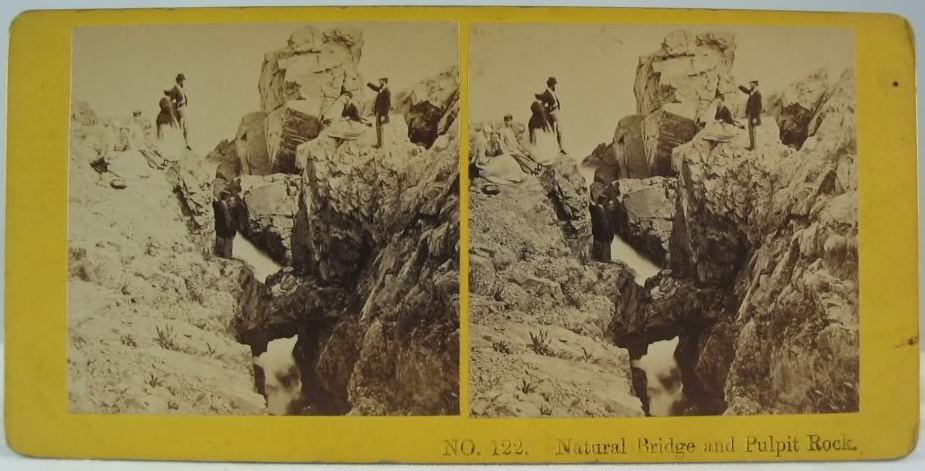

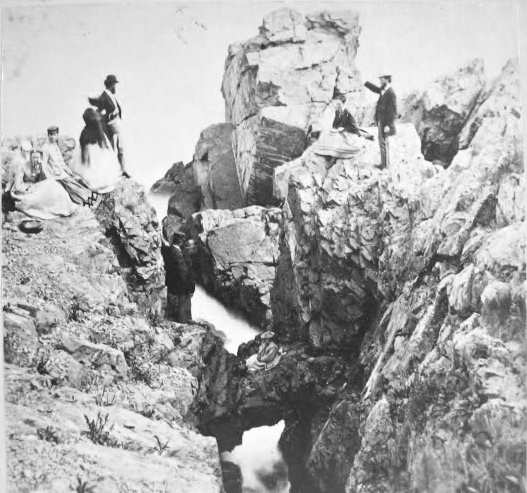

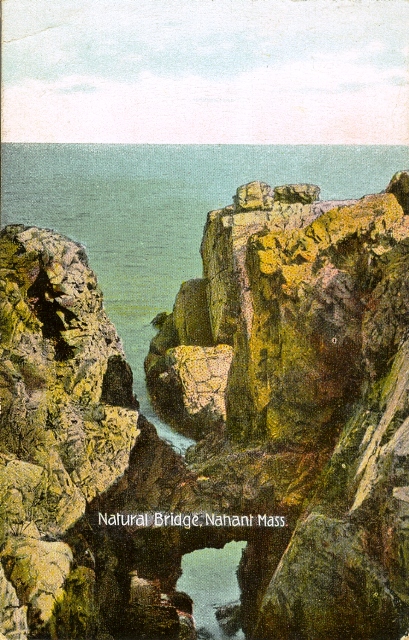

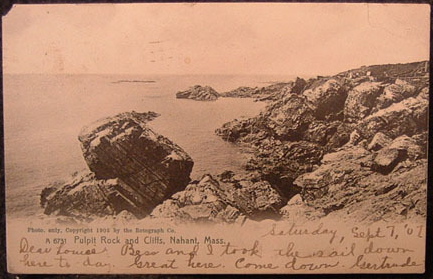

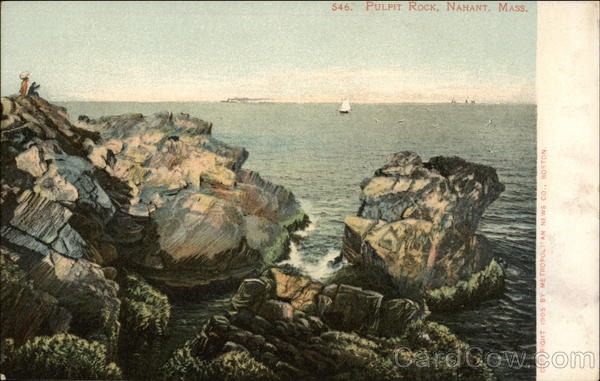

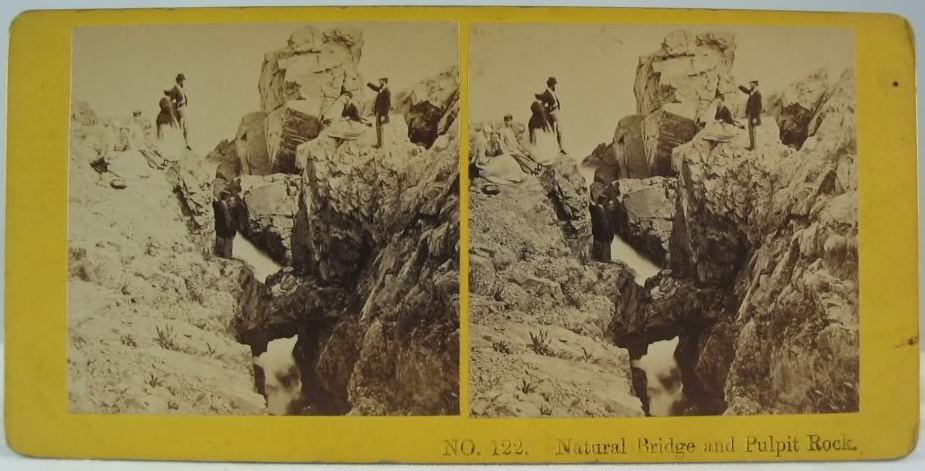

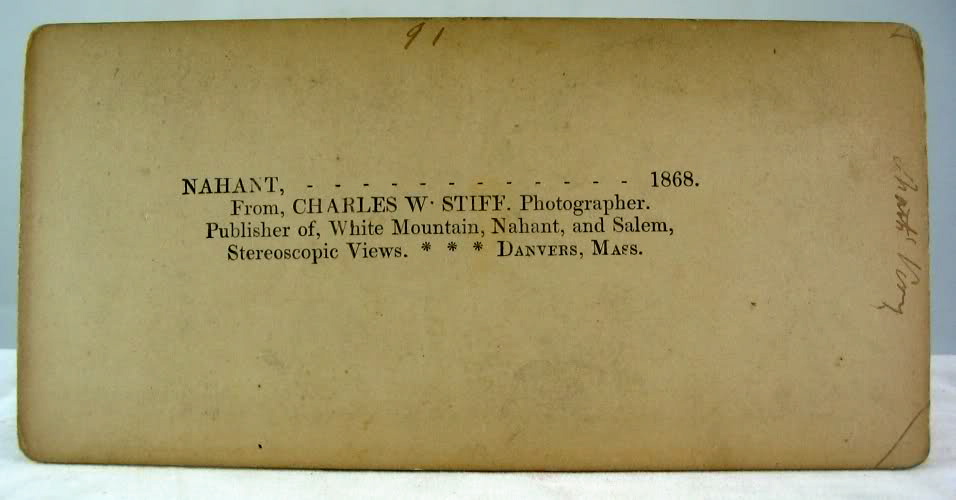

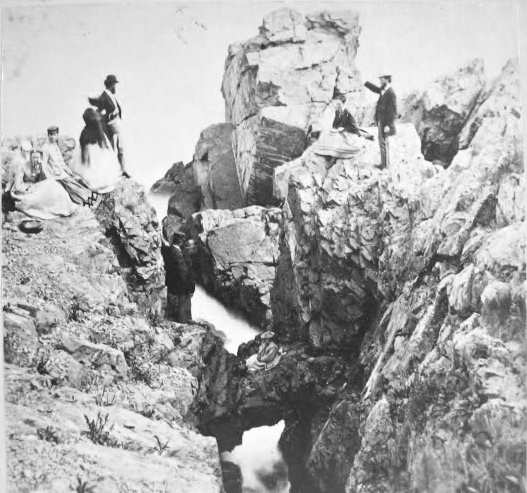

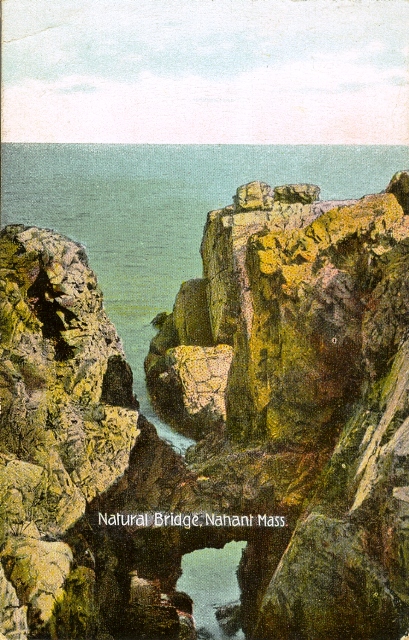

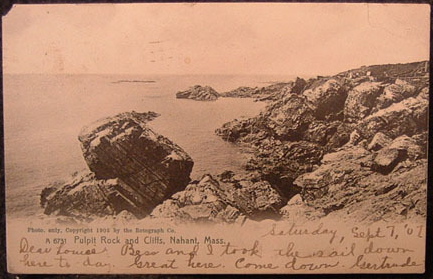

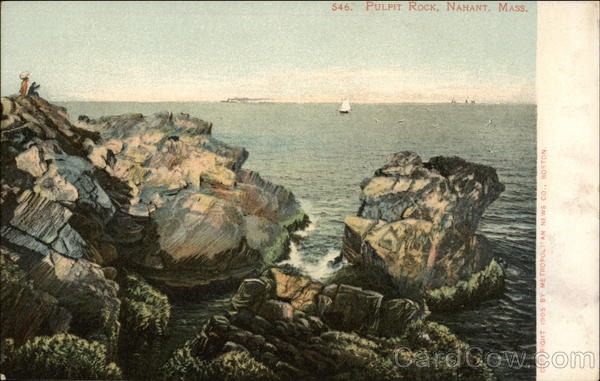

Nearly two hundred miles to the southwest of Mount Desert Island, on a peninsula called Nahant on the coast of Massachusetts, a remarkable geological formation greeted the rising sun. The formation was known familiarly as Pulpit Rock, and it attracted generations of tourists until it, along with a Natural Bridge connected to nearby rocky features, were destroyed in a fierce winter storm in February, 1957.

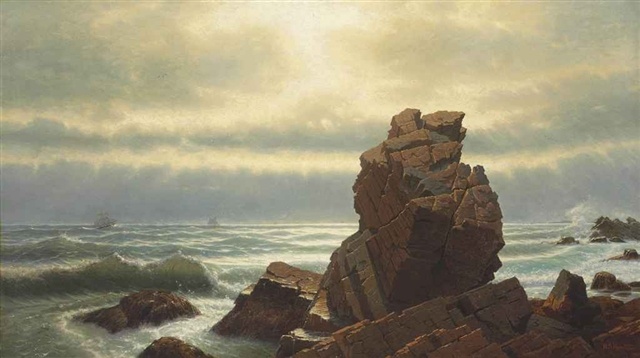

In the nineteenth century, among the many American artists drawn to Pulpit Rock was William Stanley Haseltine. In 1865 he finished a major oil painting that depicted the scene with reverential awe, backlighting the principal rock with divine illumination (Pulpit Rock, Nahant, 1865, oil on canvas, signed and dated ‘W.S.Haseltine/1865’ (lower right), 28 by 49 3/4 inches; the basis for the title is discussed in the Overview and Lot Notes sections of an auction catalog listing, here):

.

.

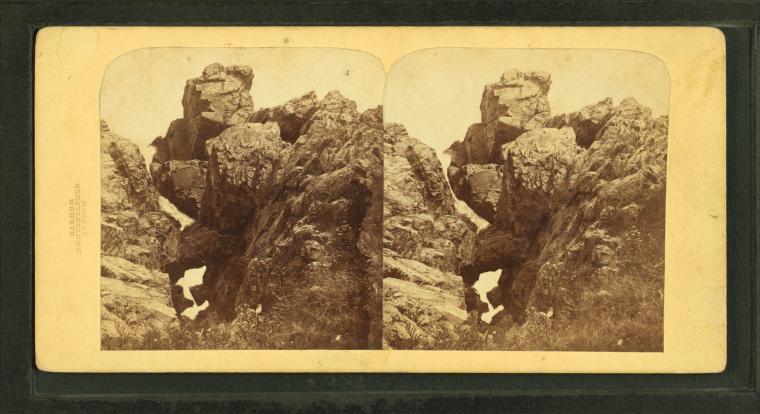

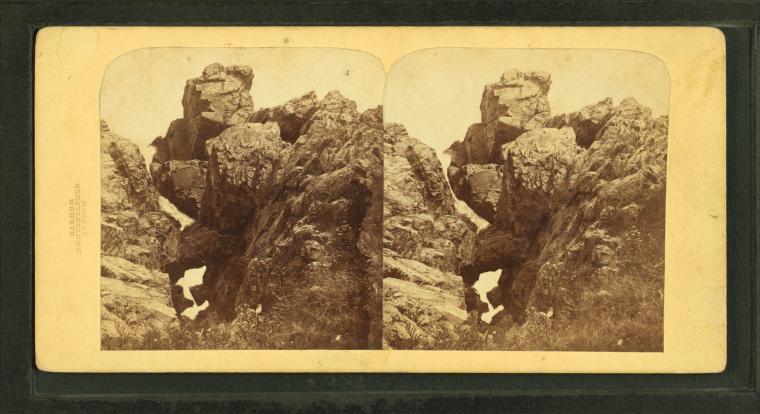

Competing with artists to memorialize the site were early photographers. Many photographic views of Nahant’s Pulpit Rock and Natural Bridge were published during the post-Civil War craze for stereoscopic views .

.

.

.

.

.

.

If you compare the first of the stereoscopic views of Pulpit Rock, above, with the drawing Haseltine made a decade earlier, you will discover — the location is a match.

.

.

.

It’s likely Haseltine used his 1859 drawing as a reference when, six years later, he began to compose his studio painting, Pulpit Rock, Nahant, although for the latter work he chose to strip away all but the central monolith, in effect de-cluttering the site for dramatic impact.

Other American landscape and seascape artists were lured to the notorious location to record Pulpit Rock from a variety of perspectives, including Thomas Cole, whose quickly rendered sketch is available here. Later in the nineteenth century, William Trost Richards positioned himself on a vantage point similar to that of the photographer of the third and fourth stereoviews, above. The result was a small watercolor (Pulpit Rock, Nahant, signed with initials ‘W.T.R’ and dated ’76’ lower right, inscribed with title lower left, 6 x 5 inches).

.

.

Souvenir postcards continued to spread images of Pulpit Rock and Natural Bridge into the twentieth century.

.

.

.

* * *

Plainly, Wilmerding was in error when asserting that the drawing by Haseltine illustrated on p. 112 of “The Artist’s Mount Desert: American Painters on the Maine Coast” was a sketch of Thunder Hole on Mount Desert Island, Maine. What’s especially regrettable is that at pp. 118-119, in his explanatory text interpreting the drawing, Wilmerding weaves an elaborate commentary premised entirely on an erroneous identification of the site. He concludes, “this drawing achieves a particularly powerful sense of location, capturing the face and personality of Thunder Hole.”

The question also arises: Where were the book’s editor and its pre-publication readers? Were they unfamiliar with the Nahant’s Pulpit Rock and its depiction by American artists?

Is there an inscription on the Haseltine drawing that may have misdirected Wilmerding and others? If so, that adds another demerit to the situation — namely, the frustratingly incomplete information Wilmerding and the book’s editor(s) chose to provide to interested readers of “The Artist’s Mount Desert.”

Here is the full description of the Haseltine drawing found in the book’s the list of Illustrations (p. 188, ill. 110):

“110. William Stanley Haseltine, Thunder Hole, Mount Desert Island, 1859. Pencil and grey wash on paper, 15 1/8 x 21 9/16 in. Private collection.”

This description presumes to assign an accurate title — Thunder Hole, Mount Desert Island — to the work. Yet, in an ostensibly scholarly context, the reader finds no information supporting the title given to this object — none of the information that, nowadays, even commercial auction houses provide when inventorying and cataloging a drawing of this caliber. Such data include:

Whether the piece is inscribed with a title, and if so, where (in this case, no inscription is visible to the reader in the reproduction of the drawing on p. 112);

What medium was used in making the inscription (pencil, ink, other);

Whether the inscription appears to have been made contemporaneously with the drawing’s completion, or whether there is something to establish or suggest that the inscription was added years later; and

Whether the inscription is by the hand of the artist, or by another hand, and if the latter, whether that person was someone knowledgable about the artist’s work (e.g., spouse or other family member, executor, knowledgable collector or scholar).

Information of this kind is essential to provide a base for subsequent scholarship.

Attention to these fine points is not an exercise in minutiae. It is a discipline that helps to avoid factual error.

.

I have retitled my William Hart painting, Pulpit Rock, Nahant, ca. 1859.

.