.

.

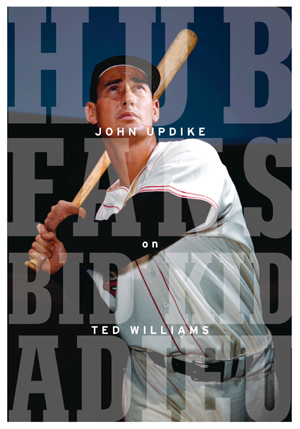

Published this week is a commemorative edition of “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” John Updike’s loving tribute to the character and craft of Boston Red Sox slugger Ted Williams. First published in The New Yorker magazine a few weeks after Updike sat in the stands of Fenway Park watching Williams’ final at bat on September 28, 1960, the essay has over the years attracted the highest praise from trustworthy observers. Garrison Keillor sums up the consensus view when he says, “no sportswriter ever wrote anything better.” The accolades are accurate and deserved.

If you follow baseball and care about its storied past, or if you admire the writing of John Updike, then you will enjoy reading this piece. If you happen to belong to both camps — if you’re both an Updike fan AND a baseball fan — then put this at the top of your list of must-reads.

The question is whether you should spend your money on this particular setting of “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.” The article is available online where it can be read for free on several websites, including that of The New Yorker and Baseball Almanac. In book form the piece has been much anthologized. It appears alongside contributions from the likes of William Carlos Williams, Don DeLillo, and Stephen King, in the elegant 721-page hardcover volume, “Baseball: A Literary Anthology.” It can be found in “The Greatest Baseball Stories Ever Told: Thirty Unforgettable Tales from the Diamond” (paperback), edited by Jeff Silverman, where it sits amongst 30 fiction and nonfiction pieces from a motley crew of writers such as Doris Kearns Godwin, Pete Hamill, Ring Lardner, P.G. Wodehouse, Vin Scully (on Sandy Koufax), and Abbott and Costello (whose “Who’s on First” comic routine is gloriously reprinted in its entirety).

The answer to why you might choose to buy this latest issuance of John Updike on Ted Williams comes down to personal preference, convenience, sentimentality, maybe even aesthetics. The essay has a special-ness to it. Its pages offer a sharp character study, a lyrical capturing of a moment of grace, and an essential moral lesson. It is, to use the corny metaphor, a small gem. Think of Duke Ellington’s description of Ella Fitzgerald: “beyond category.” The quality-conscious publishers at The Library of America respect good writing and have taken care to design the book, simply as a physical object, as an attractive product to hold in your hands.

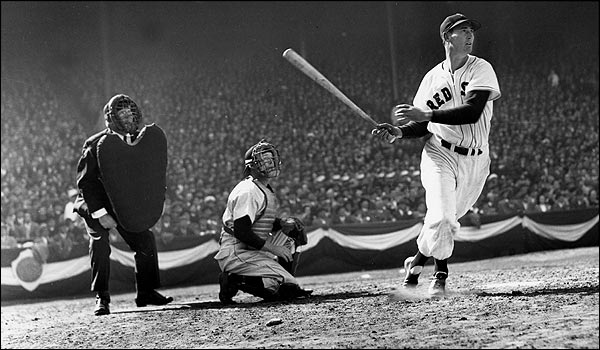

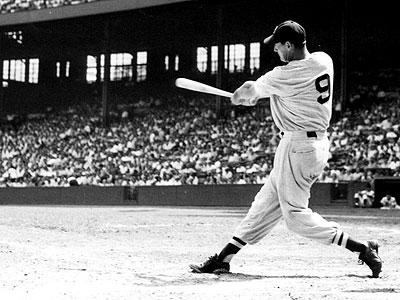

Three photos of Ted Williams grace the book: one in color on the jacket (pictured above); one in black and white that’s used as the frontispiece, showing the slugger ascending to the Fenway field on that final day; and one near-sepia in color spread horizontally across the front and back boards, freezing in time his celebrated swing — making this a hardback that looks just as fine with or without its jacket. (Updike approved the choice of photos but in a note to the editor forbade further illustrations: “There shouldn’t be too much attempt to ‘juice up’ the little volume. Austerity is always in style.”)

Inside, the main essay from 1960 (with a dozen factual footnotes Updike added a few years later) is, of course, the big draw. This text (33 pages in this wide-margined edition) is flanked by a three-page Preface, written only weeks before Updike died in 2009, and a meandering nine-page Afterword that served as an obituary for the ballplayer who died in 2002. The preface and afterward may strike you as workmanlike exercises — common stones wildly outshone by the diamond at the center of the book.

.

.

Updike’s essay begins with the stuff baseball fans demand: a concise chronicle of Williams’ unsteady two-decade career; a plethora of statistics; a swiftly delivered argument on the slugger’s position in the firmament: “From the statistics that are on the books, a good case can be made that in the combination of power and average Williams is first; nobody else ranks so high in both categories. Finally, there is the witness of the eyes; men whose memories go back to Shoeless Joe Jackson — another unlucky natural — rank him and Williams together as the best-looking hitters they have seen.”

The essay’s special hold on the reader depends not just on Updike’s extraordinary skills as a chronicler, but in the poignancy of the fact that here, at the start of his writing career, is a young author (a man of the mind) paying homage to a seasoned master (a practitioner of a physical craft) whose career is ending. It is a pairing of a novitiate with a soon-to-be retiree. Both men were unstinting strivers toward perfection. These two — one the observer, the other the observed — are well matched. Indeed, they are so “of a piece” that the reader finds the essay coming around full circle to become a profile of the author himself. It is Updike defining Williams in order to define himself. There are, to begin with, physical similarities between the men (both were a lanky six-foot-three-inches), plus some intriguing biographical congruences. In the essay Updike compares the long “affair” between Williams and Boston to a marriage (“a marriage composed of spats, mutual disappointments, and, toward the end …”). On September 28, 1960, Updike, whose first marriage was disintegrating in its seventh year, was in town to visit his new love’s apartment, and it was only because he found her absent that he decided, instead, to head over to Fenway Park.

Similarities in the two professionals’ character and aspirations are strong. Williams, in Updike’s eyes, is one of those players “who always care; who care, that is to say, about themselves and their art.” Their approach to their respective professions, baseball and literature, is identical. Updike approvingly writes that “baseball is a game of the long season, of relentless and gradual averaging-out” — as if he knew, in 1960, that the next five decades would see the release of over 60 books under his name. Was he envisioning his own hoped-for obituary when he describes Williams’ “rigorous pride of craftsmanship [that] has become a kind of heroism”? Consider their common stubbornness: here, in what is ostensibly a sports essay, Updike dares to insert references to Leonardo, Calder, and Donatello — because that’s the kind of writer he is. And, Ted-like, he gets away with it. As for Williams’ scientific interest in the muscular mechanics of swinging, Updike refers to this as the ballplayer’s “intellectuality, as it were.” You can sense the young Updike setting a goal for himself in this summation: “No other player visible to my generation concentrated within himself so much of the sport’s poignance, so assiduously refined his natural skills, so constantly brought to the plate that intensity of competence that crowds the throat with joy.” And then you come across four words that could serve as an epitaph for both men:

“A thing done well.”

.

.

Updike’s reference to Donatello’s sculpture of David victorious over Goliath appears in the course of his attempt to describe the effect of Williams’ bodily presence on base. The body is not an easy subject for American authors. Even as loose and modern an American writer as David Foster Wallace falls back on a Victorian reticence in his 2006 essay, “Federer as Religious Experience” (published in the New York Times, here) when addressing the magical physicality of the tennis great. In that profile of Roger Federer, in what is perhaps the best sports essay since Updike’s, DFW notes: “in men’s sports no one ever talks about beauty or grace or the body.”

The final pages of “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu” are a miracle; they crowded my throat with joy. Having finished his warm-up recitation of Williams’ career statistics and highlights, Updike switches back to the here-and-now, to the air of expectancy inside Fenway Park that memorable afternoon. What Updike’s writing does is conjure up the grand feeling that grabs you when the overture ends and the curtain rises. His words place us squarely among the ten thousand fans. He guides us through every phase of the ensuing wash of emotions. Common sports announcer lingo (“high fly to deep right”) is mixed with Updike’s own literary mode (‘The afternoon grew so glowering that in the sixth inning the arc lights were turned on — always a wan sight in the daytime, like the burning headlights of a funeral procession”).

Then comes a single paragraph that relays the climatic event (Williams hitting a final home run). Only when I read the paragraph again did I recognize the conjurer’s trick: Updike never uses the words “home run” or “homer” or even “hit”. Instead, the simplest of words — “it” — takes the place of those expected nouns. His pregnant prose has rendered direct identification superfluous and (in a sense) blasphemous. Here is the paragraph’s keystone sentence. Notice how the sentence builds a crescendo out of three phrases of diminishing length:

Fisher threw the third time,

Williams swung again,

and there it was.

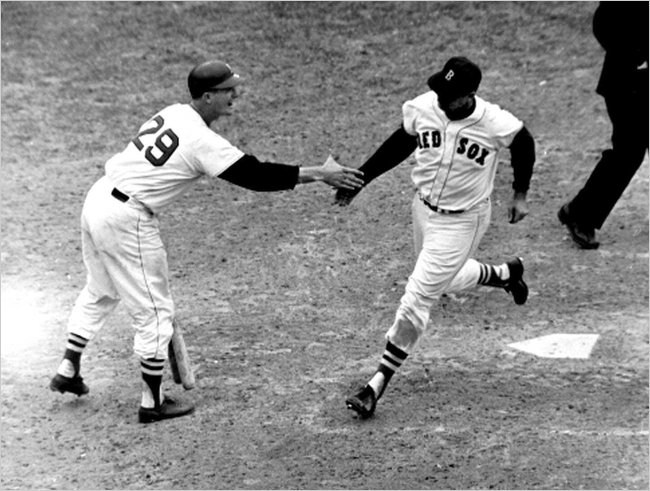

Notice, too, how the steps of the crescendo track the three elements Updike later says defined the day’s glory: “A perfect fusion of expectation, intention, and execution.” The craft behind this paragraph (and the even more memorable paragraph that follows, tracking Williams’ run of the bases and disappearance into the dugout) explains why readers of the essay often become re-readers of it. To mention one final bit of magic: We all have a cliched notion of time “standing still” at moments such as this. Updike will have none of that. He convinces us this was an episode even more mystical, a moment that touched all time, past and present and future. He writes: “It was in the books while it was still in the sky.”

A 35-second video of Ted Williams’ last at bat at Fenway Park on September 28, 1960 is available online here. If you watch it, pay special heed as Williams rounds third and heads for home. At that moment the cameraman pans up to show the crowd in the stands behind third base, the very section where, we now know, John Updike was on his feet joining in the stadium-wide “beseeching screaming.” The tape is too pixilated for us to spot him. But he’s there, absorbing the moment — and starting work on his own a piece for the books.

UPDATE (09-26-2010): From an article by Charles McGrath published (online) yesterday by The New York Times comes this photo of Ted Williams crossing home plate after hitting that homer in his last at-bat.

.

.

———-

(A shorter version of this post appears as a book review on Amazon here.)