A mission statement spells out a company’s overall purpose and provides a sense of direction to decision making. Among other things, it defines what the organization aspires to be.

The other day a friend sent me a link to a curious document that fits the general notion of a mission statement, although this one is labeled a “Manifesto.” It also fills up an entire page, making it wordier than the run-of-the-mill mission statement.

The Manifesto was generated by Thompson Hotels, a wholly owned subsidiary of a privately held real estate development firm named The Pomeranc Group. In 2007 the New York Times profiled the company’s entry into the world of boutique hotels. The firm’s growing portfolio now includes nine hotel properties.

If you go to Thompson Hotels’ black-backgrounded homepage at http://www.thompsonhotels.com you’ll be faced with a flashing series of quotations. Featured are the words of luminaries such as Che Guevara, Bob Dylan, Jean-Luc Godard, Federico Fellini, Oscar Wilde, and Jean Baudrillard. I noticed that in the hotelier’s talky firmament, the French post-structuralist Baudrillard’s star shines brightest. Two of his bons mots are offered for your delectation. Meanwhile, in the background, hip music is heard. An infinitely repeating loop plays a medley of eight instrumental selections, each abbreviated to 30 seconds. The overall mood? Retro groovy. I felt smothered by an über trendy ooze.

If you visit the homepage, and I recommend you do, be sure to click on the word “MANIFESTO” found in the top border. Or access the manifesto directly, here. On that page you’re invited to test whether your personal identity matches the profile of an ideal guest as conceived by the hotel owners. Here is the text of the Manifesto:

_________________________________________________________

Dear Guest,

In a world full of choices, we all need to question who we are and where we belong.

We set out to create a group of hotels that are effectively sophisticated and classically cool but small enough to provide personal service. Thompson Hotels are contemporary and elegant with an element of edge and surprise. At Thompson Hotels we believe there’s a place for refined, intimate style in a world of overly dressed up mega brands. We are not trendy boutique hotels. Our style is simultaneously timeless and avant-garde.

Who are our guests? Bohemian chic meets art-house-wise meets quiet yet radical elegance; really more of a mind-set than a demographic… “good looking revolutionaries.”

We wish we had known: Steve McQueen, Bobby Kennedy, Mick Jagger in 1973, Grace Kelly, Jean-Luc Godard, Edie Sedgwick and the fictional Royal Tenenbaums.

You’ll find us watching Darko, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Coffee and Cigarettes, Badlands, Blow Up, Le Mans. Or listening to The White Album, the Sex Pistols, Sinatra and we don’t pick sides between the East Coast and the West Coast.

We collect Hiroshi Sugimoto photographs, vintage Zippo lighters, matchbooks from cafes, quotes and one day, Basquiat.

We are a tribe, nomadic in nature joined by common threads. We are driving up the coast to a life of epic adventures… “It’s an anywhere road for anybody anyhow… but no matter the road is life”: Jack Kerouac.

See you soon,

TH

p.s. we will keep all your secrets and promises.

________________________________________________________

The term “fisking” is blogosphere slang for a point-by-point criticism of a statement, article or essay. The fisking process involves questioning the analytical framework of the text and highlighting perceived errors. It values close scrutiny, so the dissection usually proceeds sentence-by-sentence or paragraph-by-paragraph. After reading the Thompson Hotels Manifesto, I thought, “Now there’s a document begging for a good fisking!” I’m not sure I’m the man for the task, but what the heck, it’s worth a try. Below is my token gift to art-house wise-asses everywhere. Especially those who, due to their good judgment or bad finances or both, are destined never to find themselves embedded in a Thompson Hotel.

Caveat: It is possible the Manifesto is a small hoax, a put-on, a tongue-in-cheek bit of cheekiness designed to separate those who get it from those who don’t. By the same token, maybe my text below is too.

So. Now vee may perhaps to begin. Yes?

In a world full of choices, we all need to question who we are and where we belong.

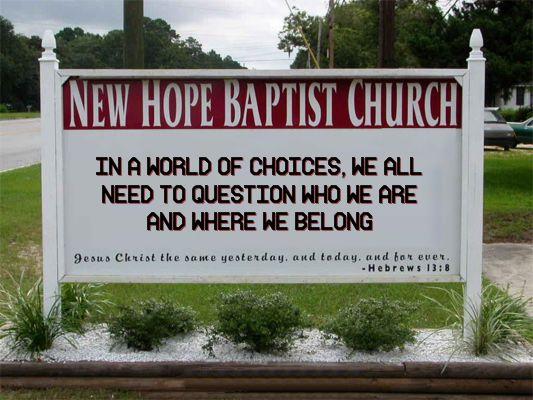

Come on, confess. When you read that first sentence, sounding so eerily like an invocation, an invitation to prayer, you sensed a spiritual touch, did you not? Maybe a tingle of déjà vu ? Oops! Lo and behold, the sentiment does fit nicely on a Church Sign:

.

We set out to create a group of hotels that are effectively sophisticated and classically cool but small enough to provide personal service. Thompson Hotels are contemporary and elegant with an element of edge and surprise.

Having established in the reader’s mind the notion of sanctuary, of a time and place for spiritual self-evaluation, the authors of the Manifesto decided to drop that idea cold. Instead, it’s full steam ahead! On to a relentless chug-chug-chug of words! The modus operandi is simple. Throw down words and phrases in hopes that something coherent will emerge. The document becomes an onslaught of adjectives, adverbs, oxymorons and proper names. Scatter shot onto the page, you watch them pile up into an enervating mass. You encounter novel compounds (“effectively sophisticated”) as inert as the arbitrary pairings formed when kids fiddle with Magnetic Poetry words on a refrigerator door.

But let’s move on to the next bit of nonsense.

At Thompson Hotels we believe there’s a place for refined, intimate style in a world of overly dressed up mega brands. We are not trendy boutique hotels.

I like how a simple declarative sentence (“We are not trendy …”) stands out amidst the lazy mush (“overly dressed up mega brands”). It turns out this defensive crouch (“We are not!”) has a back story: one of Thompson Hotels’ co-owners has been quoted elsewhere as saying, “If you call us a boutique hotel chain, I’m going to scream.” He prefers the term, small luxury hotel group. The reason has something to do with branding and status. But I am not Winston Smith (nor was meant to be) and shall not revise my text.

The term “Boutique hotel” is commonly used to describe intimate, usually luxurious or quirky hotel environments — exactly the environment the Manifesto, however clumsily, purports to describe. Check out Wikipedia’s article on the “boutique hotel” phenomenon for a consensus understanding of the term. The unavoidable fact is that these hotels are inherently trendy, occupying a segment of the industry characterized by constant churn, where players forever chase the next wave.

Historically, boutique hotels (sometimes also known as “design hotels” or “lifestyle hotels”) began appearing in the 1980s in trend-setting neighborhoods of London, New York, and San Francisco. Typically, boutique hotels are furnished in a themed, stylish and/or “aspirational” manner. The mission, the raison d’être, of Thompson Hotels is to participate profitably in this trend.

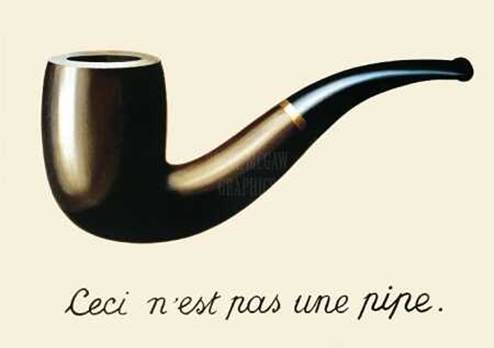

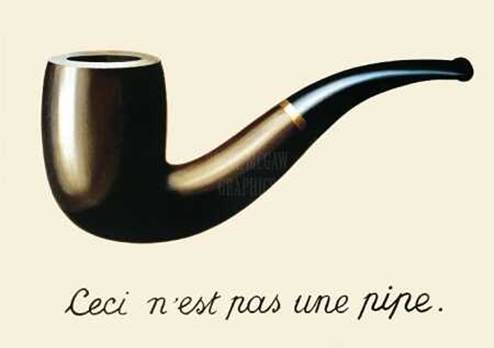

When responding to an absurd assertion, I often find it useful to summon the the clarity of the French. What’s the best way to view a trendy Manifesto eschewing trendiness? Comme ça:

Though not as deft as Magritte playing with the way we attribute significance to images, the Manifesto does serve the purpose of highlighting a complicated relationship between the company’s self-definition and reality.

Our style is simultaneously timeless and avant-garde.

Reading this sentence, I was momentarily intrigued. I like timeless. On occasion I also like avant-garde. The Manifesto brings them together again for the first time. What’s not to like? Should I worry about how stable the marriage is? No, for the moment I’m willing to play along, especially since the sentence sparks a frisson. There’s an echo of T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. In “Burnt Norton,” the first segment of that magisterial poem, Eliot posits:

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present,

All time in unredeemable.

Along those lines, did you notice the verse from Hebrews 13:8 on the Church Sign, above? Jesus is the same yesterday and today and tomorrow. The Manifesto promises your stay at a Thompson Hotel will be just like that too! Heavy, man. Could be heavenly, too. But this has got my head spinning.

I know once reason returns I will understand there is no way to halt what The Bard called “time’s fell hand” — especially not in the trendy business of boutique hotels. After all, we’re talking about an industry in which a Thompsons Hotels co-owner cited with amazement the extraordinary “longevity” of an employee who’s been with the firm a whopping six years! There are reports the company’s Gild Hall location in lower Manhattan (open for less than two years) is slated for a style makeover, as its star restaurateur is being replaced. The company used to boast about its free Wi-Fi, but this year reversed its stance in favor of charging guests an extra $10.00 a day.

Timeless? I report, you decide.

But take heed. Clouds approach. Pretentious gobbledygook lies straight ahead.

Who are our guests? Bohemian chic meets art-house-wise meets quiet yet radical elegance; really more of a mind-set than a demographic…

I was going to point out hyphenation flaws and other nits throughout the Manifesto (for those interested, a useful hyphen guide is found here; don’t say you’re learning nothing from this post). But the prospect of correcting wrong notes in this Bohemian rhapsody reminded me of the scene in Basic Instinct when Michael Douglas (Detective Curran) comes upon the injured George Dzundza (Gus), who’s been attacked with an ice pick. Curran tentatively applies a finger to block the bleeding from Gus’s neck. But then he notices, in a growing panic, the full extent of the punctures. He quickly runs out of fingers to stanch all of Gus’s fatal wounds.

I know, I know — you’re still wishing that the chain of “blah-meets-blah-meets-blah” would meet up with a meat cleaver. And I’m reminded that the “fisking” process compels me to propose a remedial measure. OK, then. Let’s add one more hookup to the chain: Bohemian chic meets art-house-wise meets quiet yet radical elegance meets Freddy Krueger.

(Really more of a cathartic comeuppance than in your fondest dreams.)

“good looking revolutionaries”

Yes, Thompson Hotels defines its preferred clientele as persons who qualify as good looking revolutionaries.

Where to begin? Smug, self-satisfied, and fatuous, this loose phrase sinks into a swamp of cynicism. The concept of “good looking revolutionaries” belongs to a place where prices are known and values ignored. Where everything is superficial, cosmetic, trivialized, reduced to fashion. As for the not pretty faces and imperfect bodies of today’s equivalents of, say, Emma Goldman, Benjamin Franklin, Albert Einstein, Francis Crick, Betty Friedan, Balzac, Gandhi?

Oh for God’s sake, we don’t want the likes of them spoiling our hotels.

We wish we had known: Steve McQueen, Bobby Kennedy, Mick Jagger in 1973, Grace Kelly, Jean-Luc Godard, Edie Sedgwick and the fictional Royal Tenenbaums.

These appear to be the hotelier’s picks for the class of good looking revolutionaries. The introductory clause (“We wish we had known …”) sets up the sad premise that these are folks no longer available to be known. They’ve passed on. They’re now guests at the Celestial Hotel. Or, in the case of the still prancing Mick Jagger, his 1973-vintage incarnation (beautiful at age 30) cannot stroll through a Thompson Hotel lobby in 2009.

The prefatory language also presupposes that the persons cited were all once capable of being known, i.e., their feet once trod the earth. News Flash: Fictional characters, such as members of the Tenenbaum family, the clan given cinematic life by writer-director Wes Anderson, were never in fact alive. Trust me on this. If “we” harbor a desire to commune with fictional beings, the first thing to do is to express that desire using different rhetoric. For example: “I wish Holden Caulfield were a real person so that I might have a chance to talk with him.”

The second thing is, “we” need to schedule an appointment with a therapist.

You’ll find us watching Darko, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Coffee and Cigarettes, Badlands, Blow Up, Le Mans. Or listening to The White Album, the Sex Pistols, Sinatra and we don’t pick sides between the East Coast and the West Coast.

An orgy of mid-cult name-dropping, these selections sound like a basket of DVD’s and CD’s that Charlie the Tuna might gather for his undersea lair. To prove his eclectic good taste.

Note the strangely truncated name (“Darko”) applied to writer-director Richard Kelley’s 2001 film, Donnie Darko. A Google search uncovers no evidence of actual people — whether they qualify as good looking revolutionaries or not — using the name “Darko” when discussing that movie. Maybe Thompson Hotels is trying to start a new trend? Say it ain’t so.

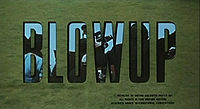

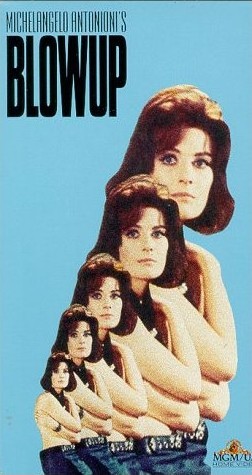

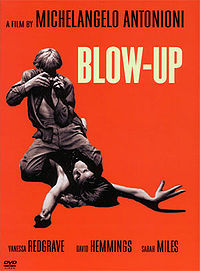

Next, notice the boast, “You’ll find us watching . . . Blow Up.” Hmmmm. It’s at this point that the needle on the Creepy-o-Meter starts to dance. Remember, this is a Manifesto presumably concocted by sophisticated advertising copywriters (correction: make that effectively sophisticated copywriters), then reviewed and approved by company management, one of whom promises to “scream” if confronted with words or terms he finds inaccurate. This means the Manifesto cannot be referring to the 1966 Michelangelo Antonioni film, “Blowup”. As shown in the screen credits (one frame of which is below), the title of Antonioni’s film is one word. While it is true the title appears hyphenated on some promotional and packaging material (as in the poster further below), it is never correct to render the title as two separate words.

Assume, then, that the Manifesto’s reference to a “Blow Up” signals something else. What might that be? One clue is that this “Blow Up” is something that can be “watched.” More particularly, it is something that you will find “us” watching. So let’s take a step back and ask, who are the “us”? Remember, the Manifesto is addressed to an anonymous “Guest” and is signed by “TH.” So “us” likely is the hotel itself, as represented by its owners, managers and staff. Or does “us” refer to the hotels’ guests? Or to both groups? What are they watching when they watch this thing called a — or the— Blow Up? An act of violence involving an explosion? A sex act? Both? Maybe posting a third quotation from Baudrillard would help readers solve the puzzle? We must work through the night to find the answer; otherwise, I fear grave consequences. Dawn may expose a pale, naked Manifesto, shorn of its raiments of erudition; a document written, edited and approved by a cadre of folks who, notwithstanding their air of knowingness, in the final analysis are (yes, it pains me to type the sentence’s final word, even though its etymology is French) poseurs.

We collect Hiroshi Sugimoto photographs, vintage Zippo lighters, matchbooks from cafes, quotes and one day, Basquiat.

More trendy brand names and other detritus. Spare me. This recalls a short-lived literary trend of a few decades ago, led by a set of young novelists. They wrote prose with copious references to trendy high-end consumer goods, discos, real life celebrities, and other pop culture stuffing. Their theory was that in our consumerist society, what you eat, wear, listen to, where you go clubbing, how you furnish your apartment, the famous people you encounter — all of that stuff taken together equals your identity. Therefore, a list of a fictional character’s recent purchases would be a valid shorthand way to construct in the reader’s mind a fully-formed fictional personage. The Manifesto shares this bleak and shallow world view. It tacitly endorses the notion that you are what you consume.

In the present text, I was glad to find a soupçon of wisdom hidden in the final words of the sentence: “… and one day, Basquiat.” Implied are the principles of connoisseurship and deferred pleasure. Collecting the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat demands maturity and a lot of groundwork. Accumulating money, of course. Finding a house or apartment with tall ceilings. Most critically, developing a discerning eye — something especially important with an artist like Basquiat whose output was of notoriously uneven quality. Assuming I’m not reading too much into those four words, the author deserves kudos for that little grace note.

We are a tribe, nomadic in nature joined by common threads. We are driving up the coast to a life of epic adventures… “It’s an anywhere road for anybody anyhow… but no matter the road is life”: Jack Kerouac.

True to form, a return to folderol. I’m hoping you, dear reader, will join with me in announcing that we are growing bored by all the silly talk coming from this other “we.” It occurs to me that you and I together are a “we” superior to the Manifesto’s “we.” We possess largeness; the author of the Manifesto’s gotta wee “we.”

(The silliness is spreading.)

As for the tribal and nomadic references, I defer to another reader of the Manifesto, a person known as “jr”. He (or, if “jr” is initials, maybe she) left a comment back in May, 2008, on a blog named Harry’s Place, in response to a piece about the Manifesto. The commenter looked at the document as a marketing effort:

I suspect the purpose of the marketing is to make you think you will be more lucky to fuck an equally desparate fellow guest at this hotel and not feel too seedy afterwards. “We are a tribe, nomadic in nature and joined by common threads” means “we want some casual nooky and we’re not thinking too much about herpes.”

Was “JR” weirdly prescient? In 2009, Alexander Wang’s limited edition designer condoms became available for purchase exclusively at Thompson Hotels properties.

p.s. we will keep all your secrets and promises.

My secret, which is not much of a secret, is that I have never been mistaken for a good looking revolutionary (alas). If you ask what I myself will keep, the answer is, I will keep my money — far away from the hands of Thompson Hotels.

That I promise.

New York City, 157 W. 35th St., September 23, 2017 at 11:45:33 AM

New York City, 157 W. 35th St., September 23, 2017 at 11:45:33 AM

Assume, then, that the Manifesto’s reference to a “Blow Up” signals something else. What might that be? One clue is that this “Blow Up” is something that can be “watched.” More particularly, it is something that you will find “us” watching. So let’s take a step back and ask, who are the “us”? Remember, the Manifesto is addressed to an anonymous “Guest” and is signed by “TH.” So “us” likely is the hotel itself, as represented by its owners, managers and staff. Or does “us” refer to the hotels’ guests? Or to both groups? What are they watching when they watch this thing called a — or the— Blow Up? An act of violence involving an explosion? A sex act? Both? Maybe posting a third quotation from Baudrillard would help readers solve the puzzle? We must work through the night to find the answer; otherwise, I fear grave consequences. Dawn may expose a pale, naked Manifesto, shorn of its raiments of erudition; a document written, edited and approved by a cadre of folks who, notwithstanding their air of knowingness, in the final analysis are (yes, it pains me to type the sentence’s final word, even though its etymology is French) poseurs.

We collect Hiroshi Sugimoto photographs, vintage Zippo lighters, matchbooks from cafes, quotes and one day, Basquiat.

More trendy brand names and other detritus. Spare me. This recalls a short-lived literary trend of a few decades ago, led by a set of young novelists. They wrote prose with copious references to trendy high-end consumer goods, discos, real life celebrities, and other pop culture stuffing. Their theory was that in our consumerist society, what you eat, wear, listen to, where you go clubbing, how you furnish your apartment, the famous people you encounter — all of that stuff taken together equals your identity. Therefore, a list of a fictional character’s recent purchases would be a valid shorthand way to construct in the reader’s mind a fully-formed fictional personage. The Manifesto shares this bleak and shallow world view. It tacitly endorses the notion that you are what you consume.

In the present text, I was glad to find a soupçon of wisdom hidden in the final words of the sentence: “… and one day, Basquiat.” Implied are the principles of connoisseurship and deferred pleasure. Collecting the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat demands maturity and a lot of groundwork. Accumulating money, of course. Finding a house or apartment with tall ceilings. Most critically, developing a discerning eye — something especially important with an artist like Basquiat whose output was of notoriously uneven quality. Assuming I’m not reading too much into those four words, the author deserves kudos for that little grace note.

We are a tribe, nomadic in nature joined by common threads. We are driving up the coast to a life of epic adventures… “It’s an anywhere road for anybody anyhow… but no matter the road is life”: Jack Kerouac.

True to form, a return to folderol. I’m hoping you, dear reader, will join with me in announcing that we are growing bored by all the silly talk coming from this other “we.” It occurs to me that you and I together are a “we” superior to the Manifesto’s “we.” We possess largeness; the author of the Manifesto’s gotta wee “we.”

(The silliness is spreading.)

As for the tribal and nomadic references, I defer to another reader of the Manifesto, a person known as “jr”. He (or, if “jr” is initials, maybe she) left a comment back in May, 2008, on a blog named Harry’s Place, in response to a piece about the Manifesto. The commenter looked at the document as a marketing effort:

I suspect the purpose of the marketing is to make you think you will be more lucky to fuck an equally desparate fellow guest at this hotel and not feel too seedy afterwards. “We are a tribe, nomadic in nature and joined by common threads” means “we want some casual nooky and we’re not thinking too much about herpes.”

Was “JR” weirdly prescient? In 2009, Alexander Wang’s limited edition designer condoms became available for purchase exclusively at Thompson Hotels properties.

p.s. we will keep all your secrets and promises.

My secret, which is not much of a secret, is that I have never been mistaken for a good looking revolutionary (alas). If you ask what I myself will keep, the answer is, I will keep my money — far away from the hands of Thompson Hotels.

That I promise.