.

.

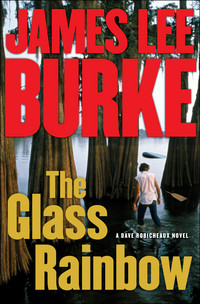

This is the latest installment in James Lee Burke’s series of crime novels featuring the New Iberia, Louisiana detective Dave Robicheaux. It finds Dave caught up in solving the mystery behind a series of murders of young women.

First things first: “The Glass Rainbow” maintains Burke’s high standard of engaging prose as the author revisits his signature theme of good and evil. As in previous outings, Dave Robicheaux’s world-view remains a tragic one. Once again Tripod, the three-legged pet raccoon, climbs trees and enjoys ice cream. Dave acquires yet another nickname (Robocop). As before, Dave teams up with his pal Clete to vanquish foes. As always, the coastal Louisiana environment, lyrically serenaded, is an ever-present protagonist, more than eager to convert to antagonist during a climactic (and, you know, not unprecedented) home-invasion episode. In short, here is everything we want in a Robicheaux novel. While “The Glass Rainbow” has its flaws, it is a fine addition to the now 18-volume series and a pleasure to read.

Picking up a newly-released Dave Robicheaux novel is like getting together with that super-charged friend from school days, the inveterate trouble-magnet, the one who long ago ventured off and settled in some exotic locale. Every year or two he pays a return visit, and so you get together for a long session of catching-up and you hear the kind of first-person stories only he can tell, told in a good-hearted, world-weary voice that commands your attention. Your friend’s character-driven tales twist and turn, shifting from factual to lyrical, from realism to the metaphysical, and then back again. His newest story ends, as they always do, in an improbably baroque climax, leaving the narrator battered but alive to see another day, leaving you slack-jawed and sated.

In “The Glass Rainbow,” each scene is masterfully constructed, building to a crescendo of tension, pushing the narrative forward with a shard of revelation. The economical way Burke sketches characters, and his visceral handling of action, are the skills of a fine craftsman. My past experience, when reading the previous novels in the series, was to come upon moments when, I felt, the pace slackened or the prose almost went off the rails. This feeling never arose with “The Glass Rainbow.”

I would not categorize “The Glass Rainbow” as one of Burke’s plot-heavy, plot-driven books. In fact, major components this ostensible whodunit are left unrevealed at the book’s end. It contains the usual cohort of colorful, sometimes over-the-top minor characters. My favorite is a wise-cracking 12-year-old named Buford who gets into snap insult contests with Clete Purcel, Dave’s longtime friend. The now adult Alafair, Dave’s daughter, has become a distinctive force of her own, possessing her own whip-smart voice in argument. Like her father, Alafair is a bundle of contradictions: a Stanford Law student with an off-the-chart IQ who is as gullible as a child; a receptive and resourceful woman who nevertheless is caught up in an obvious snare.

Fortunately for the reader, what is the irreducible core of the book, it’s true propellant, is the Dave and Clete Show. The repertoire of this pair of lawmen is broad and deep. The two call to mind Mutt and Jeff, Felix and Oscar, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. There’s more love between them than in most marriages. Their repartee now includes bittersweet reflections on growing old (or, in Clete’s case, his adamant refusal, at times, to grow up). I chuckled whenever Clete’s irrepressible descriptions of his recent sexual exploits caused the prim Dave to squirm and say, Shut up — I don’t want to hear that stuff!

“The Glass Rainbow” differs from several earlier Robicheaux books in grounding its story more solidly in realism. Earlier volumes experimented with Burke’s theme that the dead live amongst us and the past is not past but always present (a notion he shares with Faulkner). On occasion Burke eased close to adopting a Southern Gothic version of Latin Magic Realism, most sensationally in the sixth book in the series, “In the Electric Mist with Confederate Dead.” In contrast, “The Glass Rainbow” is part of a pull back, as was “The Tin Roof Blowdown,” set in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Real horrors trump imagined grotesques.

Dave and his third wife Molly now live in town. Abandoned is Dave’s former bayou home with its dock and Bait Shop that figured so prominently as a setting for the first dozen or so books. I miss Dave’s stalwart manager of the dockside business, Batiste. This means Dave’s domestic milieu lacks an immediate, immersive relationship to nature; he now only “visits” that raw natural world in his pickup. After finishing “The Glass Rainbow” it occurred to me that not once had I heard the cry of a nutria; instead, the patron animal for this book seems to be a blue heron. “The Glass Rainbow” also eschews a serious confrontation with Louisiana political power that energized earlier books (and no federal agents stop by this time either). There is also a diminished role for religion. Characters occupy a smaller circle, closer to home. While these are all losses, the situation is redeemed by the opportunity to move the strong Dave-Clete and Dave-Alafair relationships to center stage. This provides more than enough substance and depth to support a 433-page tale.

It goes without saying that Burke is in firm control of his material, yet the veteran reader may feel the author is taking a play-it-safe approach this outing. Or say that Burke’s ambitions are muted. The trajectory of the plot is more streamlined than usual, the action centered on the present day, with few flashbacks (except for asides designed to familiarize new readers with Dave and Clete’s background). There is no complex layering of multiple subplots. The cast of characters is a bit narrower than usual. All of this serves to make “The Glass Rainbow” one of the quickest-to-read books in the series.

Solving the mystery of the murders of a group of young women is not the real subject of the book (in fact, their stories soon recede into the background, and much is left unexplained at the book’s end). Instead, the focus of the suspense is on the fate of three persons: Dave, Alafair, and Clete. It is through dialog that these three are seen at their best (and worst) — and it is dialog that provided me with maximum delight, particularly when it serves as the platform for comic relief.

When the supremely self-aware Dave observes others, he lets no gesture go unremarked, no suppressed twitch unnoticed. Clete and Alafair’s perceptivity is nearly as acute. They too skillfully track the emotional states of others, except when they themselves are blinded by love. All in all, you could not ask for better guides to the moral dimensions of the story.

The real subject of “The Glass Rainbow,” as with all Robicheaux narratives, is good and evil. That is a large subject, of course. Over the course of an intriguing hour-long interview conducted with the author in 1998 (its first segment is available here), Burke made the following points:

– There is a minority of people who thread their way in and out of the fabric of society who are indeed wicked.

– Dave Robicheaux recognizes environmental and genetic sources for criminal and psychopathic behavior, but he’s most intrigued by the existence of a third category. Not directed by environment or genes, there are people “who reach a moment of choice where, of their own volition, they step across a line and deliberately murder the light of God in their soul. They eradicate His thumbprint from the soul, as Dave says. It’s a conscious choice. And they enter the Kingdom of darkness.”

– Evil always consumes itself; it’s just a matter of time. That’s not only the nature of the universe, its also the path of the human soul.

– In terms of a story line, the hand of justice works from somewhere outside of the criminal justice system.

In that same interview, Burke mentioned his belief in the presence of “the other side” (in “The Glass Rainbow,” Dave has repeated encounters with a 19th century steamboat, whose crew calls out to him to join the realm of the dead). Burke explained:

“I subscribe to a belief in the unseen. I believe those spirits [the dead] are with us. I believe the visible world is the external manifestation of one that’s far more complex than we could ever imagine in our wildest dreams. . . . I believe the world is inhabited as much by the dead as by the living.”

Are there deficiencies in “The Glass Rainbow”? Yes. A central character named Kermit Abelard, wealthy scion of Louisiana aristocracy whom we come to learn is a member of Dave’s “third category” of evildoers, is insufficiently developed. Kermit’s passivity and his lack of charisma weaken the climactic home-invasion battle, an episode which desperately needs a three-dimensional figure if it is to sustain the reader’s loyalty. A related flaw is that Kermit’s relationship with Alafair does not ring true, a condition not assisted by the fact that Burke keeps the pair’s intimacy offstage. Another disappointment is that not much is done with another favorite theme of Burke’s: the path from atonement to redemption to restoration. Significantly, this book ends abruptly, with Dave’s successful defense of his home. Unlike previous books, Burke offers us no epilogue, no period for a calm aftermath.

People new to James Lee Burke are likely to ask where they should start. Should it be with this latest release? My view is that reading the novels chronologically is ideal . . . and not very realistic since by now the size of the backlist is daunting. Plus, I suspect most fans did not follow a pristine chronological path, anyway. I first met Dave in the middle of his life (in the rambling “Dixie City Jam”). I then looped back to the starting point (“The Neon Rain”); proceeded to tear through paperbacks; got caught up; and followed him ever since.

So where to begin? Most of us, even if we hesitate to claim a single favorite Robicheaux book, do have a more-favored book — the one that inches slightly ahead of the pack. For me that book is “Purple Cane Road” (maybe because uncovering his mother’s story meant so much to Dave). Burke himself in the interview I mentioned previously said he felt “Sunset Limited” was the best in the series up to that point. When asked about “In the Electric Mist with Confederate Men,” he admitted, “I’m real fond of that book as well.” I’m guessing among serious readers there’s no consensus on which is “best”. When you consider the consistent quality of the writing, the recurring thematic concerns, and the immutability of Dave and Clete, I think the newcomer can jump in at any point. And keep in mind that if “The Glass Rainbow” provides your first introduction, Burke has already considered your situation: as the story unfolds, whenever the reader needs to know some element of Dave or Clete or Alafair’s past, Burke is there with a quick and clear synopsis.

So my advice is this: Just start. James Lee Burke is too good to miss.

(A condensed version of this post appears as a book review on Amazon, here.)