.

.

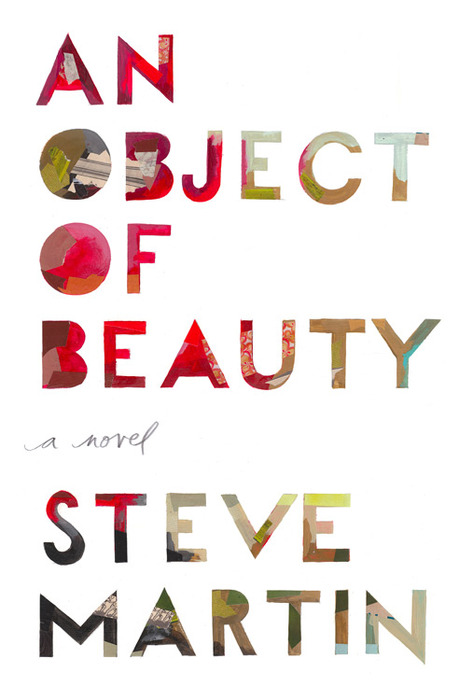

Frank O’Hara’s reputation seems caught in a holding period, an awkward stage preliminary to his work becoming universal and timeless. Consider, for example, the final scene in the opening episode in the second season of “Mad Men,” the cable TV series set in the world of advertising as practiced in New York in the early ’60s. We see the show’s protagonist, Don Draper, picking up a slim volume of O’Hara’s poems (“Meditations in an Emergency,” 1957). He recites the final lines from “Mayakovsky.” There is an ambivalence to the scene. Was O’Hara chosen less for the intrinsic merit of the poetry than to set an easy marker for a zeitgeist, the same thing the producers accomplish by highlighting the period-specific cut of Draper’s suit and hair? With friends like these, will O’Hara ever escape the mannerist ghetto of the “New York School“?

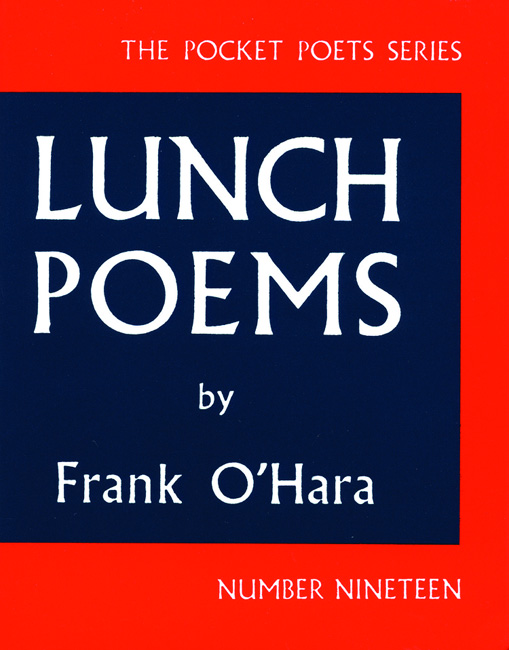

And so some readers may pick up “Lunch Poems” (first published in 1964) after seeing it praised as an emblematic cultural document of mid-twentieth century America. Yet even if the time-bound aura of O’Hara is the come-on, what makes you stay enthralled in his circle is his voice — a “thinking” voice as vitally American as Whitman or Frost.

There are 37 poems in “Lunch Poems” and their quality as well as their accessibility varies. The poems span a period from 1953 to 1964. This book is not a “best of” O’Hara collection, yet it does contain what may be his most durable poem.

A few of these short pieces are so recondite that they lose me. In a few others O’Hara raises an opaque scrim to suggest beauty beckoning from the other side, and these poems begin to “click” only after multiple readings. But the majority of the poems are freshly-minted coins granting immediate access to a lively, urbane worldview. While general knowledge of the New York cultural scene in the ’50s and early ’60s is helpful, these poems, at their best, easily communicate to us in a way undimmed by the passage of time.

Here is an endless succession of the poet’s friends, lovers, artists, musicians, and the parties, meals and conversation they create. Here are O’Hara’s travel experiences and his love of foreign languages (you could write an essay on the myriad uses of French in O’Hara’s poetry). The man wears his erudition lightly on his sleeve. He’s enamored by both the high and the low in American culture: “I am ashamed of my century for being so entertaining but I have to smile” (Naphtha, 1959). Another poem from the same year, Rhapsody, contains a premonition of his early death (at age 40) a few years later: “I historically belong to the enormous bliss of American death.”

Most delightful are his street-level ruminations, spinning in all sorts of directions, nurtured during mid-day breaks away from his curatorial duties at the Museum of Modern Art. A typical flight occurs in A Step Away From Them, which begins: “It’s my lunch hour, so I go for a walk among the hum-colored cabs.”

A new survey ranking the most walkable cities in America placed New York on top. Teju Cole’s recently published novel, “Open City,” set in contemporary Manhattan, is a current example of a continuing tradition of perambulating literary protagonists. A half century ago, O’Hara was walking these same streets, looking, speculating, daydreaming about the city. A fragment in an untitled poem from 1959 asks, “Where does the evil go when September takes New York and turns it into ozone stalagmites deposits of light?”

The cityscape serves as a platform for accessible philosophizing, as found in one of his best works: “The Day Lady Died”. Is there another poem where so much meaning resides in its title? At first glance the title rattled me, threw me off stride. In it I heard a rhythm, but an uncertain one. Then came the answer hit me: simply reverse “Day Lady” to reveal “Lady Day” — the nickname of blues singer Billy Holiday, whose dark night of the soul ended in 1959. The displaced “day,” her missing “day,” had to be displaced, it had to go missing from O’Hara’s page. The text of the poem recounts the day the poet walked the streets and avenues of Manhattan attending to errands. These everday events end when he spies a tabloid newspaper’s front page announcing Holiday’s death. It is the day after death, the first of many days denied her.

In the poem’s final stanza — in which O’Hara recalls hearing Holiday perform at the Five Spot Café — he accomplishes a wonder. He turns death into something other than displacement and omission. Memory overpowers death, converging time present and time past.

.

(An abbreviated version of this review is posted on Amazon, here.)