.

.

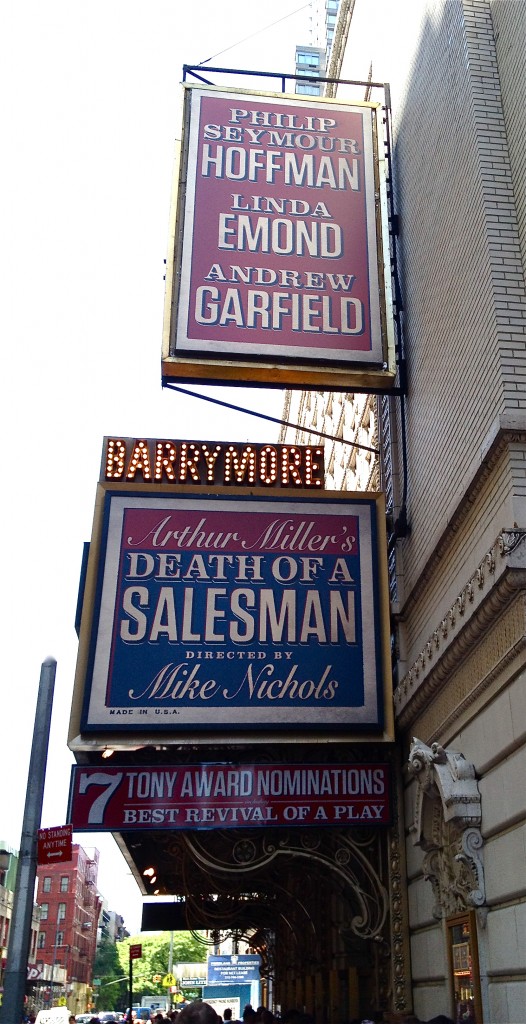

Yesterday afternoon I attended a performance of Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman” at the Barrymore Theatre. The cast of 14, directed by Mike Nichols, was headlined by Philip Seymour Hoffman (Willy Loman), Linda Emond (Linda Loman) and Andrew Garfield (Biff Loman).

The anticipation of a crowd of eager theatre-goers as they entered the theater is something I tried to capture in a video, uploaded here. What I cannot adequately capture is the general force and impact of the production we saw.

Instead, here are particular things that struck me:

Numbers. Someone could write an entire essay on the use and meaning of numbers in “Death of a Salesman.” Years, ages, dimensions, limits, prices and payments — the script is chock-full of them. The characters measure their lives with numbers. From the early flashback scene in which Linda recites the household bills needing to be paid (16 dollars on the refrigerator, nine-sixty for the washing machine, three and a half on the vacuum), to the later scene when Willy’s neighbor Charley lends him support (the usual 50 dollars plus, this time, 110 to pay for insurance), all the way through to an ending where we find Willy wondering over his life “ringing up a zero,” you can hardly catch your breath before some new numbers are announced, debated, corrected, and chewed over some more. There are the sinking salary requests made by Willy as he pleads with Howard to keep him on the payroll after he’s “put 34 years into this firm.” Willy starts at 65 dollars a week (“I don’t need much any more”), then lowers himself to 50 (“all I need to set my table”), then bottoms out at a beggarly 40 (“that’s all I’d need”). There are Linda’s imprecise references to Willy’s age (is he 60 or 63?); Ben repeating the limits of his jungle adventure (17 when he walked in, 21 when he walked out); and Willy’s precise recollection of lumber stolen for a home improvement project (those beautiful 2-by-10s). We hear of Biff’s failing math grade of 61, just 4 points way from passing — those 4 points something Willy declares he’ll gain for his son. Then a circular debate over how much of a loan Biff should request from Bill Oliver (10 thousand? 15 thousand?). There’s Linda’s mention of their 25-year home mortgage (she’s compelled to note that Biff was just 9 when they bought the house). Amid this onslaught of figures, our apprehension grows. Are numbers for Americans the preferred way to follow and ultimately judge a life?

Insurance. When, in order to aid his elder son, Willy strikes a bargain with death — twenty thousand dollars from an insurance policy (those numbers again!) — there is an echo of the climactic plot device in Clifford Odets’ “Awake and Sing,” in which a no longer useful man similarly chooses a disguised suicide to bankroll the future of his grandson.

Athletics. How fine and assuring it was to be an audience member watching Hoffman, Garfield and Finn Wittrock (who played Hap Loman) in an early flashback scene as they tossed a football around, between stage left and stage right, in a precise, easy manner.

Comedy 1. There were some awkward bursts of laughter from the audience, as when Willy repeatedly berates Linda when she tries to join in the family conversations. His bullying putdowns got laughs that were scarily undeserved. I wonder whether this was simply embarrassed laughter from otherwise psychologically astute adults who were already on to (and forgiving of) Willy’s gross and contradictory ways? I’m not sure. I think another factor might be our collective exposure to years of TV situation comedies where belittling is a staple, where similar putdowns are accompanied by canned laughter. The two times when Hap interjected his inapposite news — “I’m getting married, Pop!” — the audience roared with laughter. Were some among us hearing the voice of TV’s womanizing Joey Tribbiani (Matt LeBlanc), interrupting the banter of his Friends with yet another impossible statement?

Comedy 2. Yet how truly funny Miller can be, funny intentionally and on his terms, as in the restaurant scene in which the headwaiter, Stanley (Glenn Fleshler), tosses out a handful of lines that anticipate Neil Simon.

Blocking. For this production Nichols resurrected the set designed by Jo Mielziner for the original 1949 production. His direction featured blocking that places an emphasis on the actors’ profiles, from our viewing perspective. I’m guessing this was dictated by the set design, but I wonder whether it also is a borrowing from Nichols’ film direction. There are superb details. The last time we see Willy he is in his hoped-for garden. Centered down-stage, he looks straight ahead into the audience, talking not to himself (remember Miller conceived of the play as taking place in Willy’s skull) but in these final moments to us. This I thought was a perfect thing.

The lines we all know, still new. How right it was for Linda Emond not to specially deliver, not to call special attention to, her attention must be paid lines. How right a choice it was for her to allow those words to emerge as a seamless part of her argument for loyalty. How right her decision to permit those words to appear new, just as they were received as new by audiences attending the original production. The same sureness was evident during her speech at the funeral scene, done so quietly, a simple “I can’t cry . . .”.

Delayed catharsis. Then something occurred I’d never seen before at a staged performance of a tragedy. When the tragedy is ended and the curtain falls and then rises to reveal the cast, by convention the magic is broken and we return to our lives. But at the end of this “Death of a Salesman,” the full cast of 14 appeared linked hand-in-hand, and the entire troupe was dour faced. The four principals stood before us in the middle of the line with faces frozen in the very same shock, sorrow, and grief of the funeral scene. They remained so. Our loud standing ovation could not break the cast’s concentration, could not entice them to adopt the ecstatic mood of our side of the proscenium. Catharsis would not be shared just yet. It was as if a spell had taken hold of the actors and would end only if we sufficiently witnessed their pain. And so, after what felt like minutes, the focus resolved on Hoffman, who moved ever so slightly forward. The burden lifted when he smiled with pride.

.

.

Also in attendance. At play’s end, after exiting the row, I noticed the actor John Turturro walking up the aisle behind me, and though I tried my best to overhear the conversation he was having with others about the performance, I was not close enough to hear particulars. Drat. A compensatory thrill came earlier. Sitting in seat K-115, the aisle seat, was an elderly gentleman who, I learned, was 97 years old. His caretaker, a young woman, sat between us. After he cracked a joke about hoping to see at least three more years’ worth of plays, I asked if he had seen this play before. Yes, he replied, he saw it during its first Broadway run. (That would have been in 1949 or 1950!) I wanted to ask if he would tell me more of what he remembered, but the show was about to start and he had turned his attention to the stage.

Trivial questions I have. What is Linda’s backstory? Was Willy eligible for Social Security benefits? What are the odds the insurance company will successful rebuff the family’s claim? Viewing the Loman house as a character, were Miller and Mielziner familiar with the illustrations Virginia Lee Burton created for her 1942 children’s book, “The Little House“?

Why did this production succeed? A revealing, hour-long interview with Nichols and his three leads, conducted when the when the play was still in rehearsal, can be found here.

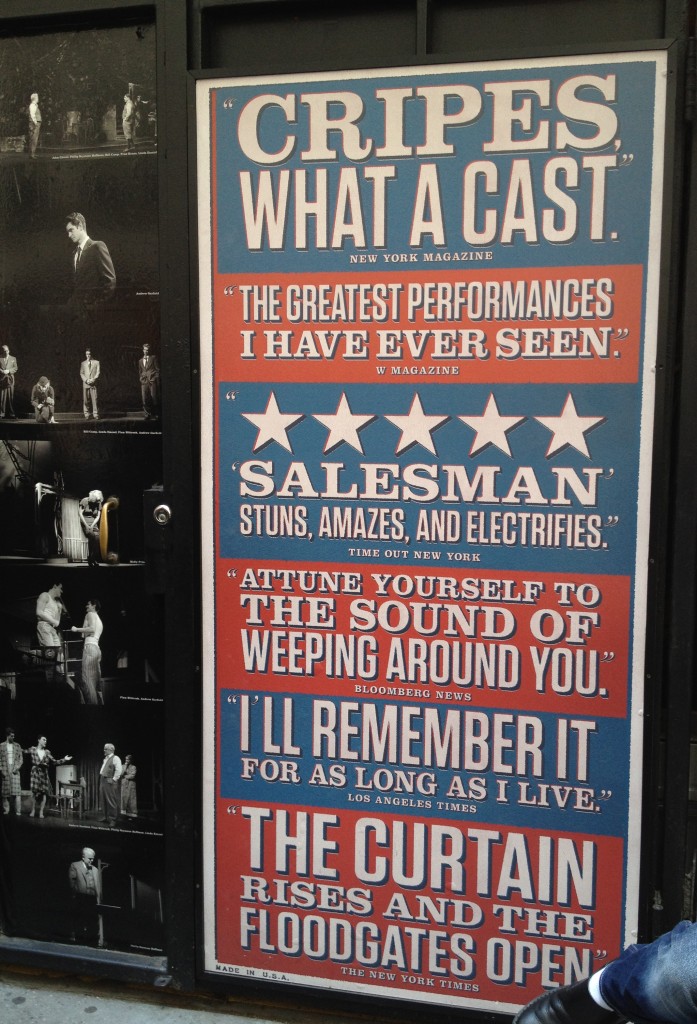

Time for effusiveness. The topmost quotation in the sign posted next to the stage door is right on the money. Hell, the whole sign is right on the money:

.

.