.

.

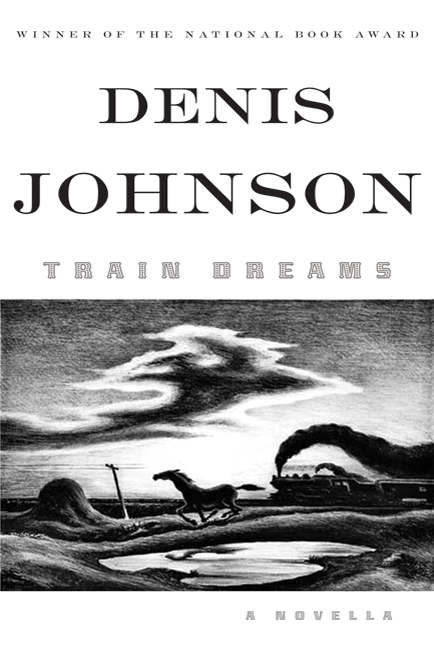

Denis Johnson’s “Train Dreams” is a well-wrought story of an American life. Its power will remind the reader of other durable works in the canon of American literature.

The book’s backwoods setting and the stoic philosophy of its characters have sympathetic ties to Hemingway’s early Nick Adams stories set in the Michigan woods. It’s laconic protagonist, Robert Grainier, is an heir to the solitary fate of men found in Jack London’s man-against-nature tales. Grainier is an uneducated man, a day laborer, and it is the hard work of living that Johnson attends to most sensitively. His interest in this common man is reminiscent of Steinbeck’s attention to the kindred spirits populating his short novels of the Depression era. As well, Johnson’s prose — simple, direct, unmannered — employs an an oft-used American style.

Yet there is nothing derivative, nothing imitative, nothing second-hand or second-rate, in “Train Dreams.” This is a stand-alone classic.

Here is a mystery: While the novella recounts a man’s life, the narrative structure Johnson adopts owes nothing to the usual forms that typically command the allegiance of the reader of life stories. The book does not take the form of a journey or an adventurous quest. It follows no easy arc that might help to confer some apparent purpose. Spoken words are few. Gainier’s taciturnity is matched by a mind unreflective, or at best only quietly reflective. How, then, does “Train Dreams” draw us in so close to an embrace that we feel its emotional force?

That’s a question to keep in mind when, a few years from now, you again pull this slim volume from the shelf or fire-up your e-reader . . . and settle in for a second reading experience.

Notes:

1. There is a free audio excerpt of the first five pages (3 ½ minutes, as read by Will Patton) available online at the publisher’s website, here.

2. Among reviews in mainstream media outlets, James Wood’s high praise in The New Yorker (Sept. 5, 2011, pp. 80-81; online here [subscription required]) is worthwhile as it discusses how the book relates to Johnson’s other works. But be alert that Wood’s piece gives away much of the plot and broadcasts many of the book’s specific beauties which ought to be left as surprises. Wood writes not so much for the potential reader as for those interested in testing its themes after completing the book.

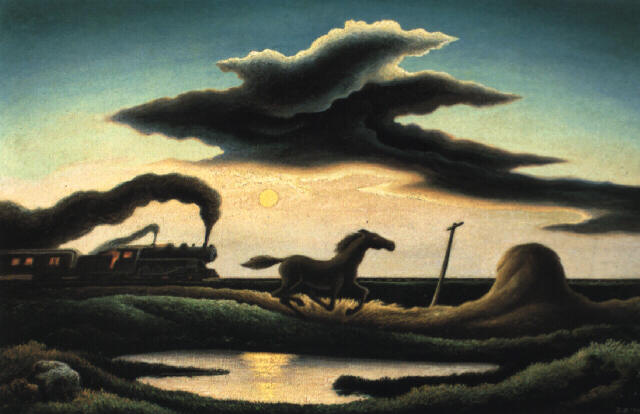

3. Many people are mentioning the captivating book cover illustration. It is a reproduction of a lithograph (produced in an edition of 250 impressions in 1942) by the American regionalist artist Thomas Hart Benton. Two years later Benton reworked the image as a painting, reversing the direction of movement, adding color, and assigning to the new canvas the sentimental title, “Homeward Bound”:

.

.

A hearty debate could be launched among readers as to whether the black and white image of “The Race” appropriately conveys the theme of “Train Dreams.” Does the wild horse represent the essential character of Grainier? When asked to describe the inspiration for this print, Benton said it was a “common enough scene in the days of the steam engine” to see “horses so often run with the steam trains” (but by the 1940s and the advent of diesel engines the phenomenon had ceased). I think the cover illustration fascinates us because of the horse’s devotion to a quixotic pursuit fueled by an urge to outlast the devilish machine nipping at its tail. Is it fair to say a comparable emotion and a comparable pursuit characterized Grainier’s life?

4. Some reviews mention a version of this novella appeared previously. The question arises, Did Johnson make any changes? I was able to compare the text of the just-released book to the text found in the Summer 2002 edition of The Paris Review, at pages 250-312, where the story made its first appearance. The two versions track exactly, paragraph for paragraph. The only edits I spotted are insignificant: in Chapter 2, the original measurements “one-hundred-twelve-foot” and “sixty-foot-deep” have been replaced with their numerical equivalents, “112-foot” and “60-foot-deep”; and, also in Chapter 2, an originally all-caps statement, RIGHT REVEREND RISING ROCKIES!, has been replaced with its lower case equivalent, right reverend rising rockies!

.