.

.

Are you wondering the same thing I’m wondering? Would you like to call the senior editor at Knopf to the witness stand to answer a few questions starting with this one: Why this book?

The “New Stories” half of “We Others: New and Selected Stories” by Steven Millhauser occupies just 144 pages. Does the publisher view us readers of Millhauser as an impatient lot, unable to wait the few years it would take this methodically productive author’s backlog of unpublished stories to grow from the seven found here to a total of, say, a dozen? Why not wait for enough material to satisfy our expectation for a hearty, stand-alone book of new stories? And what about the back half of the book — the “Selected Stories” compilation? Does this indicate Knopf considers Millhauser undeserving of a “Collected Stories” compilation (the treatment respectfully accorded Lydia Davis, Amy Hempel, Grace Paley, Deborah Eisenberg and others)?

The 14 previously published stories, which come from Millhauser’s four books of short stories, are:

From “In the Penny Arcade”: A Protest Against the Sun; August Eschenburg; Snowmen. From “The Barnum Museum”: The Barnum Museum; The Eighth Voyage of Sinbad; Eisenheim the Illusionist. From “The Knife Thrower”: The Knife Thrower; A Visit; Flying Carpets; Clair de Lune. And from “Dangerous Laughter”: Cat ‘n’ Mouse; The Disappearance of Elaine Coleman; History of a Disturbance; The Wizard of West Orange.

Millhauser explains in his “Author’s Note” how he worked past initial trepidation to pick these pieces: “I chose stories that seized my attention as if they’d been written by someone whose work I had never seen before.” Millhauser fans may object to the omission a favorite or two from his inventory, but I think he generally made good choices. This compilation will allow a new reader to get an honest perspective on Millhauser’s work. So: the book may be an excellent gift idea.

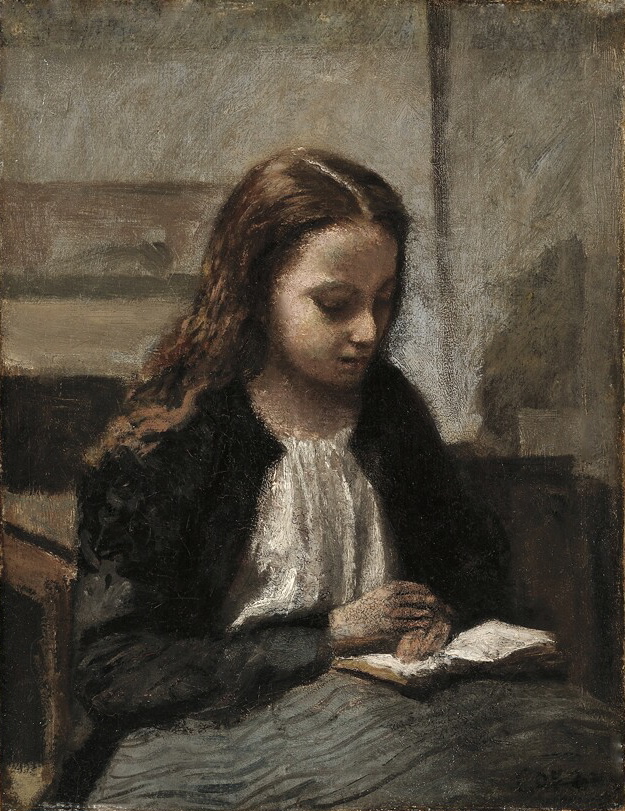

Part of the pleasure of reading Millhauser (who is on the faculty at Skidmore College’s Department of English) is to enjoy the ways in which his literary inspirations flavor his writing. Even when his plots are ensconced in late 20th or early 21st century settings, something in the atmosphere, some note or tone, will harken back to 19th century American writers, especially Hawthorne and Poe. When a protagonist proclaims that “anxiety’s our pastime, desperation our sport,” one is reminded of the restlessness, the fevered unease (nay, panic) that seizes so many narrators of that period. Then, too, there is the author’s infatuation with T.S. Eliot’s The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock. Most boldly, in the story Klassic Komix #1 (collected in “The Barnum Museum”) Millhauser re-conceived Prufrock’s anxious meanderings in the form of a 44-panel comic book. Now, in one of his new stories, we read of a similarly drifting character emerging from his lonely room with desirous thoughts — thoughts that parody Eliot’s lines (note, for example, what happens to Prufrock’s final fantasy of becoming a pair of ragged claws scuttling across the floors of silent seas):

“. . . one has come down from the attic in search of — in search of what? Shall we say, a pleasant encounter between two like-minded souls, in a suburban living room, of a September eve? And yet the craving to reveal ourselves spreads in us like a disease. It’s also true that we long not to be seen, never to be seen, to live out our existence — our existence! — like growths of mold in the depths of forests.”

While Millhauser is not breaking any new ground in the seven new stories, I perceived a heightened emphasis on what in one story he calls “a savage loneliness of which you can know nothing.” Opening with “The Slap” in which a quiet suburban community attempts to fathom the meaning of a stealthy stranger who randomly approaches residents and delivers a slap to their face (“we had been violated in some definite though enigmatic way”) and ending with “We Others” which is narrated by the ghost of a recently-deceased doctor who self-examines his attraction to a couple of lonely women (“our desire is infused with a darker, more ferocious longing: the desire for all that we have ceased to be”), these new tales are a continuation of Millhauser’s hallmark obsessions played out within solidly crafted surreal worlds — worlds which mirror what we understand, perhaps mistakenly, to be our real world.

.

An abbreviated version of this review is posted on Amazon, here.