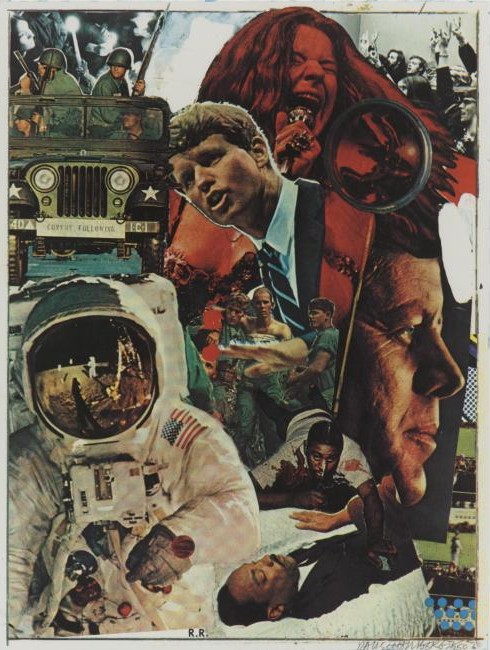

This is the first piece of art I bought. It’s a silkscreen print created by Robert Rauschenberg. He titled it “Signs.”

Rauschenberg conceived of “Signs” as a summation of the 1960s. The piece was an aborted commission for a magazine cover. Rauschenberg released the work in June, 1970, through his gallery affiliation, Castelli Graphics, in an edition of 250 signed impressions.

The 60s had turned Rauschenberg into a politically engaged artist, and he probably welcomed the challenge of coming to terms with a decade of seering experiences. Exercising his natural affinity for collage, he would try to make sense out of an explosive arc of events that most observers felt defied all sense. Raushenberg said the print “was conceived to remind us of love, terror, violence of the last ten years. Danger lies in forgetting.”

I see “Signs” as an achievement at once topical and timeless. Topical, obviously, since the artist has brought together a dozen immediately recognizable 60’s images — photos that were then still fresh with pain and joy. Topical in a slightly broader manner as well, since the picture serves to encapulate the baby boomer generation’s creation myth. But timeless also, thanks to the artist’s genius in re-fashioning stark images into something whole, something coherent, something aspiring to the redemptive.

“Signs” belies the rap too often laid on Rauschenberg — that he surrendered to an aesthetic of “messiness.” I was surprised to find such trash talk being repeated by the perceptive Louis Menand in his recent essay on Donald Barthelme, a modernist author who, Menand argues, boldly borrowed Rauschenberg’s collage approach, and with it made a notable contribution to literature. (The article, “Saved From Drowning; Barthelme Reconsidered,” appeared in the February 23, 2009 issue of The New Yorker, available online here.)

Distinguishing Rauschenberg’s methods from those of previous collagists, Menand makes the following assertions: “[T]raditional collage arranges fragments into a form, and Rauschenberg’s collages are not organized in any ordinarily legible manner. … Most of Rauschenberg’s work … has no center. Form, in the conventional sense of a hierarchical order, is one of the things he is trying to eliminate.” Menand sees Rauschenberg’s signature work as embracing “the illogic . . . the apparent absurdity . . . the arbitrary juxtapositions of radically disparate materials.”

My purpose in this post is not to quibble with Menand’s characterization. His article focuses on style, not on the decipherment of any particular work of visual art. And who can deny that “messiness” nicely recapitulates the ’60s decade itself.

Rather, my purpose is to celebrate Rauschenberg’s triumph over formlessness when constructing “Signs.” I want to praise his decision not to echo chaos or succumb to absurdity. I want to show how he chose instead to commandeer art’s arsenal against entropy.

How did he do this? Through compositional devices, juxtapositions, reconciliations, and slights of hand that are deft, resonant, poignant, and funny. Logic, not illogic, informs this work of art. It’s there for all to see:

Tripartite form: I think even on first encounter the viewer senses both stability and energy in “Signs.” A feeling of stability derives chiefly from Rauschenberg’s reliance on a structure of three vertical segments nestled in a rectangular confinement. Up the left side we see a moon-walking Buzz Aldrin claiming a large chunk of space in the frame; above and behind Aldrin is a four-man Army jeep, and above and behind that is a candlelight peace vigil. The right side is topped with another black-and-white photo, this one of students attending an anti-war teach-in (the left and right corners are nicely balanced). Below this the artist has positioned a professional photo portrait of a visionary-looking John F. Kennedy, tucked beneath which are a few stills from the Zapruder film that captured JFK’s assassination. Sandwiched between left and right flanks are puzzle pieces that rise like a totem pole. Starting from the base, this central composition comprises five elements: (1) the body of Martin Luther King as he lay in state at the U.S. Capitol; (2) a fallen victim of an urban riot; (3) two Vietnam soldiers flanking and supporting a wounded comrade; (4) Bobby Kennedy in earnest oration; and (5) Janis Joplin in wild performance. The five stations of this central vertical segment are strengthened by an overlapping and interweaving of its parts: for example, two arms, one begging, one blessing, reach over MLK; RFK’s hand slices through the Vietnam scene, in a call to halt the bloodshed.

Hierarchical order: This piece most definitely has a “center.” The central totem is a well-ordered pillar of life, a hierarchy of energy, a flow of life force. It begins in silence with a photo of MLK in his coffin, his blood stilled by death. It steps up to the bloodied man fallen in an urban riot. It rises next to a trio of troops, wounded, bleary, yet upright. It climbs to catch Robert Kennedy in the middle of an impassioned but controlled speech. It crescendos with the ecstatic singing of Janis Joplin. Think of it also as a fountain of youth — all of its featured players are young (MLK, 39; RFK, 42; Joplin, 27) — but one tinged with irony. Only a few months after Rauschenberg completed his composition and released it to the world, Janis Joplin, his friend and fellow escapee from Port Arthur, Texas, died of a drug overdose. With that death, the vector of the totemic form was altered. No longer an unstoppable upward force, it now circles back on itself. It has become a circle of life.

Cohesion through repeated motifs: With the possible exception of eyes, the human organ or appendage most crucial to an artist is, I would argue, the hand. “Signs” is largely a composite portrait, which means it is all about faces. But to my eyes it is the hands in “Signs” that resonate most strongly. Notice how Rauschenberg emphasizes their physical meaning while also teasing out their symbolic importance. A hand may choose to grip a bayoneted rifle to control others, or hold a candle in a hopeful prayer, or grasp a tool of communication (a microphone) to express freedom. A hand’s fingers may splay to signify peace or extend to confer a blessing over the dead. Our pride in seeing the iconic image of an American astronaut standing on the lunar surface is tempered when we realize that the sole visible hand of Buzz Aldrin is, in fact, not visible at all. The hand is protected, swaddled like a mummy, rendered uncommunicative, unlike the vulnerable but expressive hands of earthlings here below. As for the “face” of America’s technological triumph, it too is so denatured by protective gear as to become literally a “faceless” achievement.

Unifying light: The strong sun and shadow on Buzz Aldin’s space suit blend seamlessly with the other wholly disparate components of the assemblage. Rauschenberg achieves compositional coherence by making two tears in the material, at the top and right edges, to reveal a white underlayer. We “read” this exposure as the source of bright light unifying all parts of the composition. In addition to its formal function, the light poignantly supplies a sacred nimbus around the late RFK’s head. It may remind us of a painfully ironic fact: in the 1960’s, men of heart were extinguished, one after another, by head wounds.

Meaning through color, direction, and tilt: To begin with the most obvious color cliche, Janis Joplin is red hot. Then, in the upper left corner’s overlapped images, note how the intense color of the guards gives way to calmer gray tints of a time-hallowed prayer for peace. Consider also the way in which the dull unlit eyes of the vehicle’s headlights are shamed by the insistent glow of lit candles. See how the quartet of uniformed men looks left (symbolically toward the past), their eyes shrouded from view, while the lone female representative of the vigil crowd turns her face rightward to meet the future. If you stare at “Signs” long enough may experience a mild case of vertigo, as there appears to be no pure vertical line anywhere in the composition, no steadying plumb line straight down to the earth. With the possible exception of the central image of wounded troops, every component is tilted slightly, as if confounding gravity and the comfort of rest. This floating quality is consistent with Rauschenberg’s practice, in art works he called “combines,” of eschewing a sense of up or down. In “Signs,” I think these off-kilter notes lend energy and flow to the work. This is an appropriate way to express a dynamic, unstable period.

Surface versus depth: In their original condition, the dozen photos that Rauschenberg selected to fill the rectangle differed in their objectively measurable proportions, lighting sources, coloration, and focus, and many other inherent qualities — not to mention differences in the sensibilities of a dozen different photographers responsible for the images. There is every reason for the assemblage to fly off in all directions beyond the frame. Yet somehow the pieces settle into position, inviting the viewer to proceed with decipherment. One thing that locks the parts into place is a bit of legerdemain, namely, the appearance of a round, clear glass paperweight on the flattened surface plane, just to the right of Joplin’s microphone. Its clever purpose is to arrest fugitive movement. We also notice a scraped trail, yellow in color, leading up to the paperweight’s current resting place, suggesting that the weight recently migrated diagonally from a position atop the fallen riot victim, stopping atop Janis’s tossed hair — hair the large convex lens magnifies and swirls into a psychedelic hallucination.

Generosity of details: After all these years there are parts of “Signs” that newly intrigue me. I’ve mentioned the intricate interweaving of imagery in the central “totem” which required careful scissoring of figures; why then is the JFK photo the only one with a sharp right angled corner left intact? Why no contouring, no integration of that photo? And is that a snippet of a Lichtenstein pop art painting under the President’s nose? What is the meaning of the eleven blue dots in the lower right corner, traditionally the location for the creator’s signature? Bullet holes? Is it fair to say the decade was “signed” by gun violence?

Irony and humor: Ironic visual juxtapositions abound in Rauschenberg’s work. Here, in the upper left a military jeep purports to escort a trailing “CONVOY,” while the only group that’s “FOLLOWING” is a peace vigil in repose. Also on display is tongue-in-cheek ribaldry. Note how RFK’s mouth, at a moment formed into a suckling shape, approaches Joplin’s breast. The rectangle’s black border can sturdily contain every image, except for two forces that pierce the top margin: the thrust of a bayonet (does its violation of the skin of the piece account for the drops next to RFK’s hand?) and the force, like rising red molten lava, of a volcanic Janis Joplin. In a final flourish, the artist asserts his dominance: small block letter initials — R.R. — resting on the bottom margin, are so powerful that their strength can lift up, and playfully tilt, a hero astronaut.

____________________________________________________

“Signs,” screenprint (silkscreen, silk screen, screen print) in colors, 1970, signed in pencil, numbered [my impression is numbered 40/250] and dated, lower right, on wove paper, published by Castelli Graphics, New York, 35 1/4 by 26 5/8 inches; 895 by 677 mm. Purchased from Makler Gallery, Philadelphia, March, 1977. I first saw the work not at a gallery but at a museum exhibition, the 1976 Rauschenberg retrospective exhibition staged at the Smithsonian’s National Collection of Fine Art (now the National Museum of American Art) in Washington, DC. One room in the show was devoted to prints, one of which was “Signs.” I was so bowled over by its power that I vowed to acquire an impression of the print, at whatever sacrifice it took.

__________________________________________________________

UPDATE 06-14-2009: Today I came across a blog posting that provides additional background on the genesis of “Signs,” including key details that I believe had not previously been published. According to an article posted on hamiltonselway.com on July 21, 2008, entitled “Rauschenberg – part 1,” the work was initially commission by Time magazine:

“’Signs,’ 1970, was originally created as an illustration for a Time magazine cover that would herald the 1970s. Rauschenberg felt, however, that the 1970s was really a continuation of the 1960s and inserted images of Janis Joplin, Martin Luther King, the moon landing, and the Kennedy Assassination. The cover was rejected by the Time Magazine editors who wanted to look forward to hopefully better times than the tumultuous 60s. Leo Castelli (Rauschenberg’s dealer at the time) stepped in and published a photosilkscreen edition of the collage.”

I’m struck by the joy expressed by Rauschenberg enthusiasts, as in this essay by John Haber on the occasion of the Rauschenberg retrospective in NYC over a decade ago: http://www.haberarts.com/rschberg.htm. Can any other recent artist match him?