.

.

“See if you can’t get something better on the radio! I mean who can dance to that stuff?”

.

The years from 1940, when he was 21, to 1948, when he was 29, were spent by J.D. Salinger as a novice writer on the make. He knocked out about two dozen short stories and was able to sell most of them, for good money, to popular magazines of the day. He dismissively referred to those magazines as “the slicks,” and he regarded his writings as apprentice work. Forgotten is what he wanted them to be. When an unauthorized edition of 22 of his early stories was released in book form in 1974, Salinger broke his long-standing silence. He called the New York Times to complain, saying, “I wrote them a long time ago, and I never had any intention of publishing them. I wanted them to die a perfectly natural death.” He was frank in self-judgment: “I’m not trying to hide the gaucheries of my youth. I just don’t think they’re worthy of publishing.”

Literary critics consider the early stories as preludes to Salinger’s mature output. The shift to a higher mastery — the emergence of that unmistakable Salinger voice — occurred in 1948. That was the year he entered into a committed, regular and productive relationship with The New Yorker. It lasted until 1965 and witnessed the creation of most all of the short stories the author later judged worthy for preservation in book form, in a volume titled Nine Stories. This period also produced four longer works chronicling the Glass family; these were collected in Franny and Zooey in 1961 and Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction in 1963.

Until recently, the uncollected early stories have been available only in bootlegged or otherwise inconvenient forms. For example, there is set of online texts, in a format that not easy on the eyes, here.

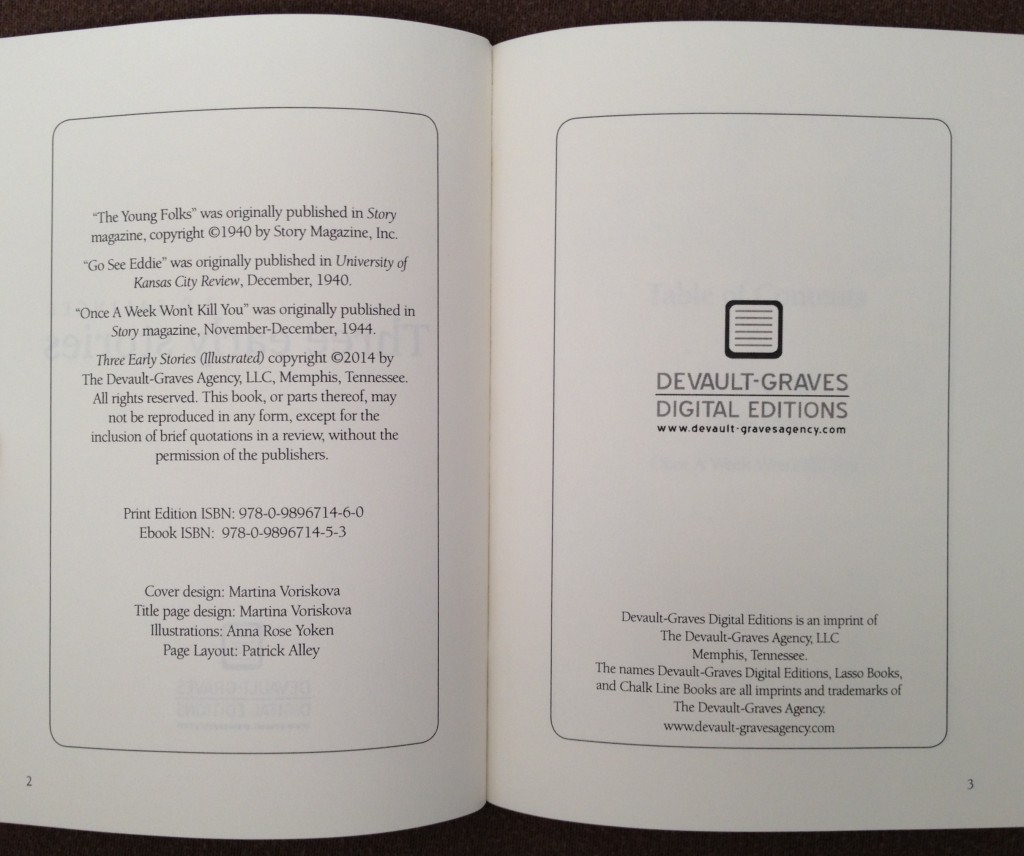

But now comes a slim, comfortable-in-the-hand volume of Three Early Stories issued, in apparent accord with copyright law, by the Devault-Graves Agency, Memphis, Tennessee (74 pages, published June 1, 2014). Like a minor spill escaping the pressured confines of a dam, this is a harbinger of a larger flow of uncollected and unpublished material we Salinger fans are eager to see released over the next few years.

A Small Sampling of Apprentice Work

The book opens with the author’s remarkably self-assured first published story, “The Young Folks” (1940). It recounts a minor episode in which two young adults fail to connect — something that was to become a signature Salinger interest. Next is “Go See Eddie” (also from 1940), an augury of the writer’s later fetishization of secrets. The book closes with a demonstration of Salinger’s sentimental edge, in “Once a Week Won’t Kill You” (1943), whose protagonist is about to leave his young wife for service in World War II. It addresses a condition described by Saul Bellow as being a “dangling man.” It happens to describe Salinger’s own status at the time that he wrote it.

Each of these three early stories is surprisingly brief, occupying on average a mere 11 pages in length. This is about one-third the length of the average story in Nine Stories. In fact, the shortest story in Nine Stories is twice the length of the longest of the Three Early Stories. To put this even more starkly, Nine Stories gives the reader nine times as much material as the combined word count of Three Early Stories. The slimness of the book is not evident at first glance. But when you hold the book open, you see that the text is printed on the right side only. Except for the ten full-page illustrations by Anna Rose Yoken, the pages on the left side of the opened book are blank.

What you get in Three Early Stories is a trio of sketches. Or think of them as hors d’oeuvres, never intended to be a fulfilling meal. Because of the modesty of their scope and their detachment from a major enterprise, these tales naturally encourage the reader to focus on their atmosphere and immediate effects.

Period Pieces with Undertones

I you’re like me you’ll quickly be reminded that the pre-war world Salinger depicts is a peculiar one, filled with quaint manners and voices, as different from our lives in the 21st century as are the diaphanous conversations and characters found in The Great Gatsby. Salinger’s characters often describe other people “swell” and “grand.” All too often they speak in italics. Their lives transpire indoors, which lends a “staginess” to the action. It occurred to me that what Salinger did was transfer to the written page the rhythms and gestures, both vocal and physical, of Broadway drawing-room comedies and dramas of the period.

I was struck by two things specially. One is that none of the three stories contains children. To a reader versed in Salinger’s world, their absence will may be keenly felt as a disappointment. The other surprise occurred when, in “The Young Folks,” I came across a sentence whose oddness seemed un-Salinger like. It’s at the point in the story when a young man and woman who have just met and are are getting to know each other get up from their chairs. Salinger writes: “They arose simultaneously. Edna was taller than Jameson and Jameson was shorter than Edna.” This threw me for a loop. Is this reciprocal statement just a clever way of underscoring the pair’s sort-of-unusual height relationship? Is it a flashy way of shifting perspective, allowing Edna to notice she is taller than the young man she’s been introduced to, while also allowing Jameson to notice he is shorter than the young woman? Is this edging toward being a bit “meta”?

On a darker note, each reader must decide for themselves whether to forgive some off-putting elements such as a languorous air of privilege among the dramatis personæ, and the author’s focus on male leads who are moody and irritable. If you’re familiar with Salinger’s biography you know he was not particularly kind to women, and your may detect in these early stories a foul odor of misogyny in the treatment of the female leads. Salinger delights in dissecting characters who are snobbish, phony, petty, none-to-bright, and of dubious morals.

That Salinger Style

The reader familiar with the arc of Salinger’s writing will recognize in Three Early Stories other elements of his style that will reappear, in glorious form, in his later works. Three Early Stories, small though it may be, provides an opportunity to confirm what Ian Hamilton wrote in In Search of J.D. Salinger, A Biography about the importance of these early exercises: “[They] had taught him to handle the mechanics of narrative with a technician’s self-assurance.”

Sure enough, from the very start the guy had the goods. You may be taken with the wizardly way Salinger propels his narratives through dialog — arch, well-honed, slangy and character-defining. The most radical honing occurs when Salinger chooses to withhold from the reader one-half of the conversation — is there another author who can match Salinger’s clever presentations of just one side of a telephone cal (a structure not coincidentally exploited by stand-up comics from Bob Newhart to Ellen DeGeneres)? (The “reveals” in the plot are carefully placed (so don’t drop your attention; when reading “The Young Folks,” for example, remember to count the cigarettes). His use of “misdirection” means you may be surprised in a good way.

Then there are the habits and idiosyncrasies we’re used to if we’ve devoured the books from Catcher in the Rye through to Seymour: An Introduction. Here they are in their earliest incarnations. Characters yawn in each of the three early stories. They bite their fingernails. Everyone smokes cigarettes pretty much all the time, and the many rituals tied to that habit are meticulously observed. Relationships, whether they are between young singles on the prowl (The Young Folks), or between brother and sister (Go See Eddie), or between a young married couple (Once a Week Won’t Kill You), are fraught with insincerities and disappointments. Human beings are “bored or apprehensive, annoyed or resigned.” Their typical reaction is . . . to try to get something better on the radio. Yet in the final story, written at the time when World War II was intensifying its brutal course, Salinger introduces more consequential themes: irretrievable loss, remembrance, caring.

.

.

Final note: Salinger never liked the illustrations magazine editors sometimes attached to his early stories in the slicks. It was shabby interference with his work, he felt, and it was one more reason he yearned for the respectful editorial hand at The New Yorker. One wonders what he would have thought of the illustrations by Anna Rose Yoken found in Three Early Stories. Ron Charles, editor of the Washington Post’s Book World, doesn’t seem concerned about this disrespect. I don’t see any value in the illustrations, several of which are too cutesy for my taste, others tone-deaf to the text. A striking error appears in her picture of the standing figures of Edna and Jameson on page 14 of “The Young Folks.” Yoken shows Edna as several inches shorter than Jameson, subscribing to the conventional girl-boy relationship. The question is, what parts of Salinger’s description on page 13 — “Edna was taller than Jameson and Jameson was shorter than Edna” — did Yoken fail to understand? Or was this an act of willful defiance on the part of the artist against the author? Or a simple oversight and “oops”-worthy mistake we all make? And why was this error not caught by the editors prior to publication?

.

Tags: "Go See Eddie", "Once A Week Won't Kill You", "The Young Folks", Anna Rose Yoken, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ian Hamilton, J. D. Salinger, Salinger